Malaysia is poised to enter a new era of criminal justice.

On 3 April, Parliament voted for the abolishment of the mandatory death penalty by passing two bills repealing the fatal punishment in all 11 offences to which it previously applied, including drug-related crimes, murder and terrorism. The move would enable judges’ discretion in serious criminal cases and also replaces life sentences with 30-to-40-year prison terms.

“Today’s vote has been a long time in the making, and while there is still more to be done, it lays the foundations for further reform that must put human rights and fair trial proceedings front and centre,” stated Katrina Jorene Maliamauv, executive director of Amnesty International Malaysia, in a press release after the parliamentary vote.

The bills aren’t yet finalised and must still be approved by the Senate and signed by the king.

However, the legal community is confident the bills will pass into law. Malaysia put a moratorium on the death penalty in 2018, halting the procedure until lawmakers could finalise a definitive legislative amendment. The country has experienced political turbulence since then, including a succession of four prime ministers in as many years, all of which delayed the drafting of the abolition bills.

In the meantime, 1,320 people have remained on death row, their lives dangling by an uncertain thread. These prisoners may begin seeking legal assistance to appeal for judicial reviews of their cases within the first 90 days of enactment of the new law, whenever it comes.

However, even though the new amendments allow discretional power to replace the death penalty with alternative measures, judges may still hand down execution orders in exceptional cases. This frustrates some human rights groups which have long opposed the death penalty for all crimes without exception.

“While the end of the mandatory death penalty is an important step, it should not be the last,” Jorene Maliamauv said. “Malaysia can and must swiftly work towards scrapping the death penalty once and for all.”

Kitson Foong, a prominent criminal defence lawyer in Malaysia, also believes the current bills are just a first step towards the full abolishment of the death penalty.

“The government can only move a small step at the time to avoid a backlash from victims’ families or the victims of violent crimes who want an eye for an eye,” he said.

In a media statement on the bill abolishing mandatory death sentences, Parliament set out the balance between the sanctity of life and justice in an attempt to reduce these possible tensions.

“The abolition of the mandatory death penalty aims to value and respect the life of each individual, at the same time, ensure justice and equality for all parties, including victims of murder, cases involving drug trafficking, as well as victims’ families,” the statement read.

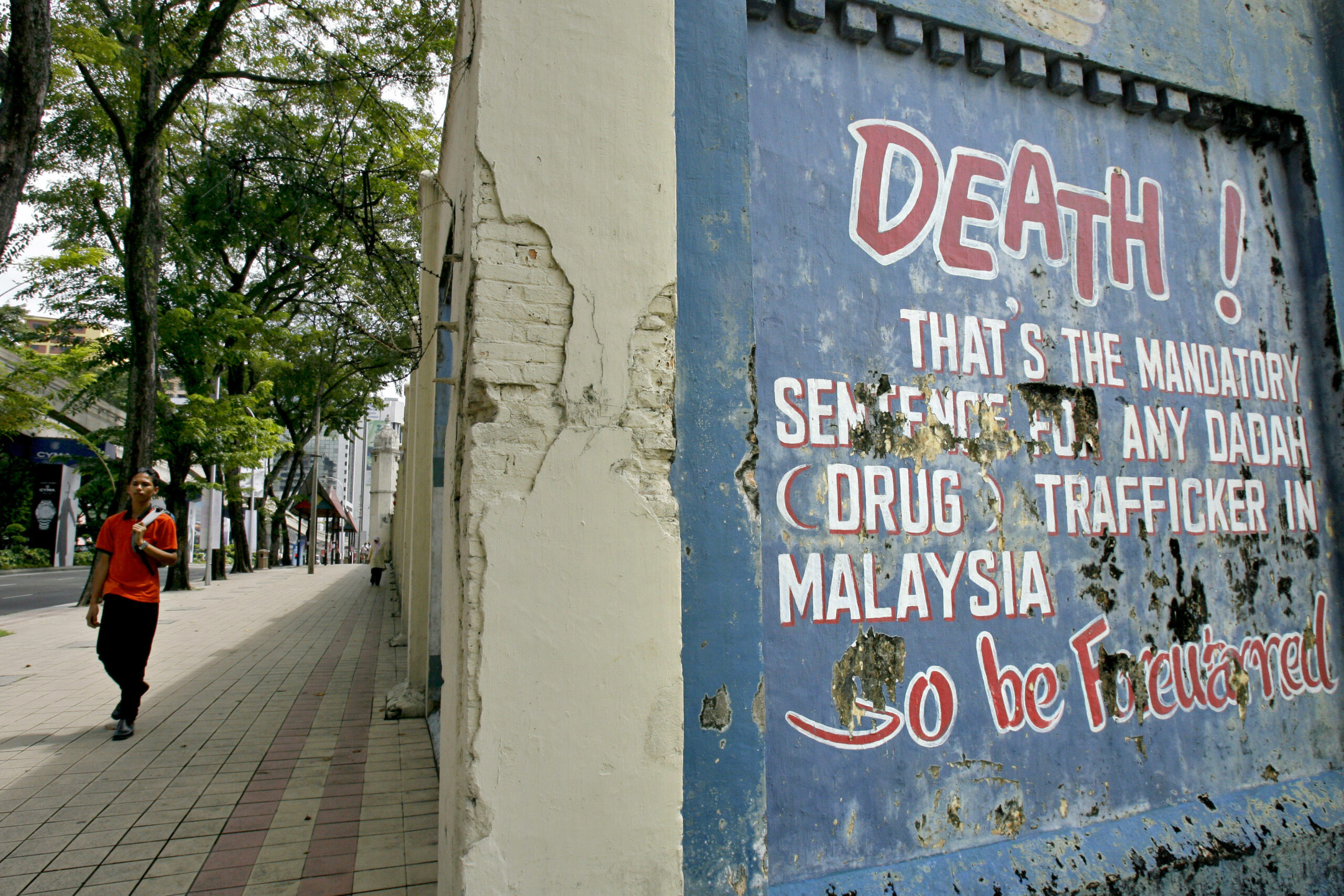

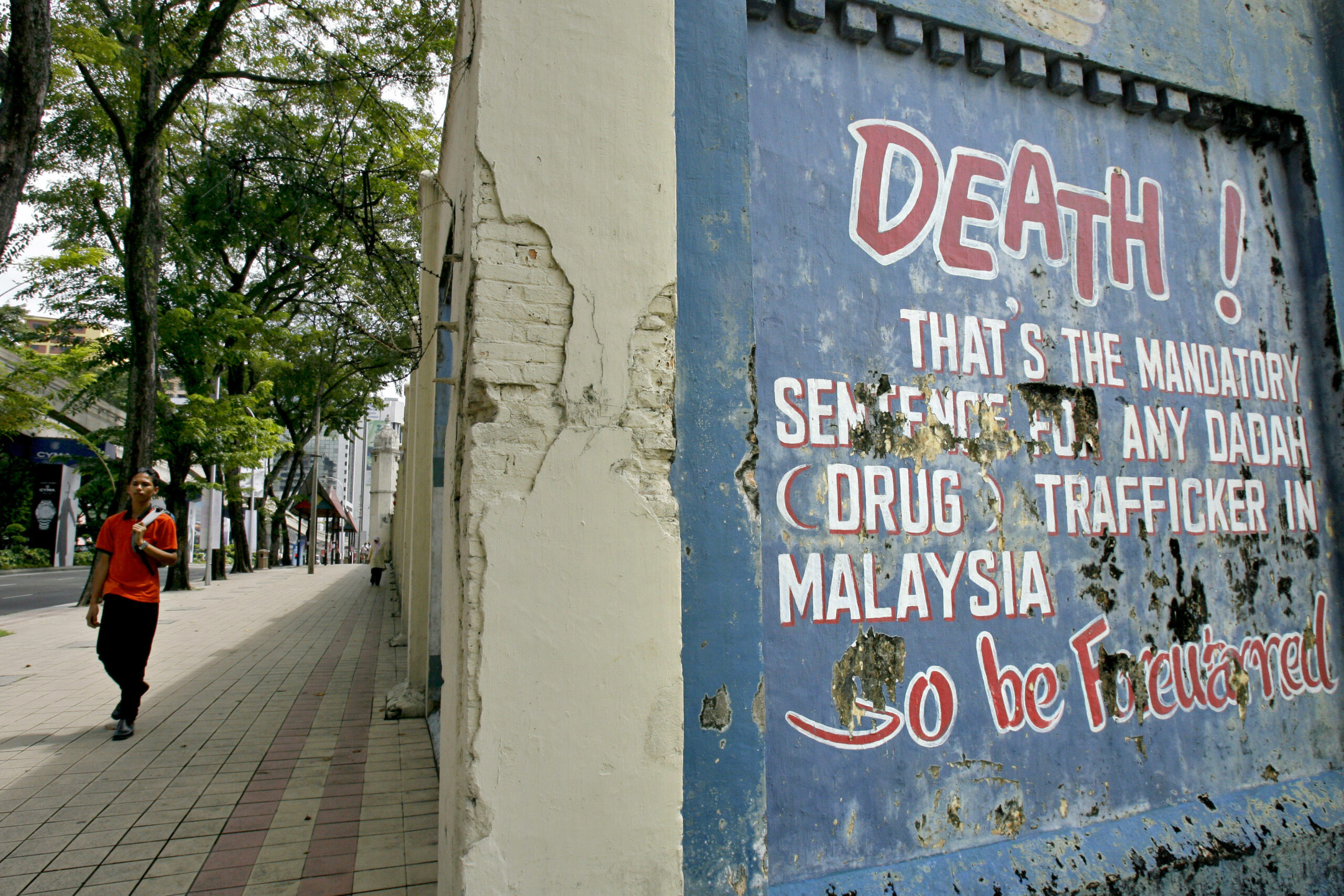

History of the death penalty in Malaysia

Capital punishment in Malaysia has been part of the country’s criminal justice system for almost a century, since before its independence in 1957.

As the country never signed the 1966 International Convention on Civil and Political Rights or its optional 1989 protocol on the abolition of the death penalty, Malaysia today remains one of the few countries worldwide that practises capital punishment. It is also among only 15 countries that impose it for drug-related offences.

On a national level, death penalties are imposed by nine laws and applicable to 33 offences, including the 11 crimes that, until yesterday, carried a mandatory death sentence.

Parliamentary discussions about the abolishment of capital punishment effectively began in October 2019. But it was only after the execution of 11 people last year in neighbouring Singapore that human rights organisations escalated the pressure on Malaysia to repeal its own death penalty.

“All eyes are now on Malaysia’s Senate to take the next steps and make these reforms a reality,” Jorene Maliamauv said. “The death penalty is the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. It is a violation of the right to life.”

Abused on death row

A 2019 report by Amnesty International argued that repealing the death penalty would also reduce authorities’ arbitrary use of violence against detainees. According to the report, those on death row convicted of drug trafficking would often be tortured, beaten and otherwise violated by detention staff and during police interrogations.

Even after it halted executions in 2018, Malaysian courts continued to apply mandatory death penalty sentences. This led to a fast increase in the number of prisoners housed on death row. With insufficient space, Foong said, they now live packed in small rooms under inhumane conditions.

“This is not fair,” he said. “Being sentenced to death is already enough of a mental toll for the inmates. Keeping them in prison in such conditions and not telling them when it will all end is just unnecessary torture.“

This is especially unfortunate for those who are charged despite claiming to be unknowing drug couriers tricked or forced to commit crimes, Foong argued, drawing from his three decades of experience defending criminal cases.

In the state of Selangor, he added, more than 60% of drug-related cases in the Criminal High Court ended in death sentences for such people because the judges had no choice.

“We are now very relieved that the government has now turned the agenda into law,” he said. “This proposed law is just the first of many steps towards the complete abolishment of the death penalty.”