Don’t run. Travel in groups. Carry an umbrella and wear sunglasses on the back of your head.

These are some of the ominous warnings issued in Australia each spring, as magpies and humans begin their annual turf war.

Streets and parks become a battleground, as the birds – descending from above and attacking from behind – swoop down on anything they fear poses a threat to their offspring.

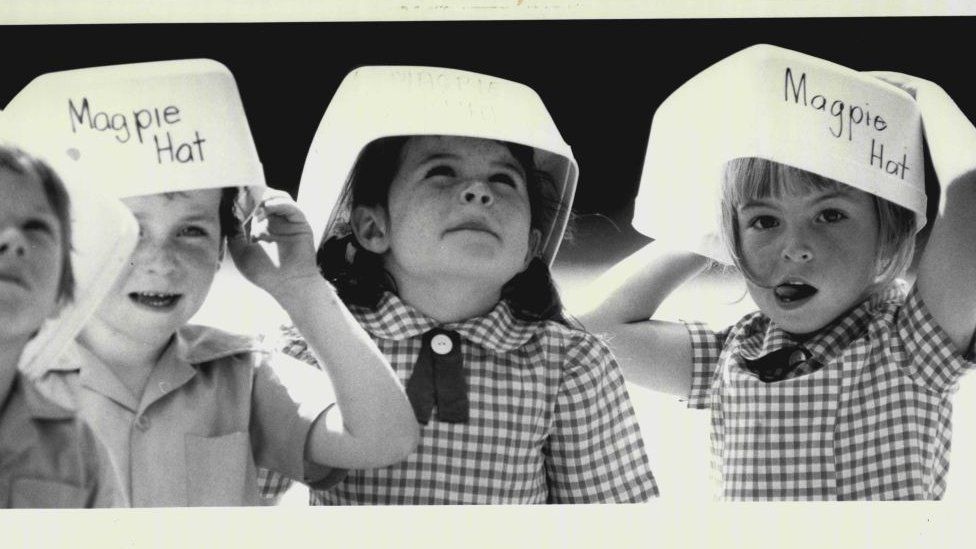

High up in their nests, they rule over their kingdom with an iron claw, while on the ground, humans dust off their protective hats – traditionally a plastic ice cream container – and duck for cover.

At times drawing blood, their ambushes can cause serious injuries, and in a handful of cases, death.

But experts claim magpies are misunderstood and humans are the aggressors.

And they want you to know peace is possible.

Brainy birds

Magpies are arguably the country’s most polarising bird.

Named after their resemblance to the Eurasian magpie, to which they are not actually closely related, Australian magpies are a protected native species, and to some, a beloved national icon.

Their beautiful warble is a quintessential Australian sound and, as predators of many pests, they are vital to the country’s ecosystems.

They are also incredibly intelligent – so smart they have even been caught helping each other unscrew scientific tracking devices – and they have also been known to strike up long-term, meaningful friendships with humans.

One Sydney family even credits a rescued chick named Penguin with helping them recover from a catastrophic accident, a heart-warming tale which grabbed global headlines and has since been turned into a best-selling book and a film.

Found in droves all over the country, such is their fanbase that in one 2017 poll magpies were voted Australia’s favourite bird and massive shrines have been erected in their honour in two Australian cities.

But there are also plenty of people who struggle to get past their divebombing antics.

The whir of flapping wings; the glint of a sharp beak in the sun; a flash of their reddish-brown eyes – all enough to strike fear in the hearts of many children and adults alike.

“I am genuinely terrified,” Tione Zylstra tells the BBC.

The 21-year-old’s local train station is vigilantly guarded by a magpie, and during breeding season it plays target practice with her head weekly.

“They’re silent killers… I’ll just see this shadow over my head getting bigger and bigger and bigger.”

“I have asthma and I would be sprinting, having an asthma attack on the train, just to get away from this magpie.

“I don’t know why it hated me, but it did… I never did anything wrong, I swear!”

Why do magpies swoop?

Australians are well accustomed to swooping birds – there’s plovers, noisy miners and even the kookaburra.

But magpies are considered the ultimate “swoopy boy” and few people are without a story.

Only a very small portion of male magpies engage in the practice though, and when they do, it’s to protect their nests during breeding season, from August to November.

Experts say they do not swoop unprovoked.

But they also say magpies can interpret simple gestures like running through their territory as a slight, and not only can they recognise individual faces – they tend to hold a grudge.

“Let’s say you’ve shown some kind of response by waving your arms or trying to hit the bird away from you,” says animal behaviourist and Emiritus Professor Gisela Kaplan, who literally wrote the book on magpies.

“That act is a declaration of open war. A magpie interprets that as a sign of aggression and will then always swoop that person from then on, every year.

“[And] somebody of a similar build, a similar height and hair colour may get mistaken in their fury, or anxiety.”

They have also been known to pre-emptively target cyclists and children because they don’t trust them – cyclists because “magpies think as little of covered faces as people in banks do of [those] in balaclavas”, and children because they are “less reasonable and may be a greater risk”, Prof Kaplan says.

For most people who are hit by magpies, it is a cut or scratch.

But they have been known to blind some – in the last fortnight a cyclist made the news after revealing a serial dive-bomber had left him needing major surgery and a prosthetic eye lens.

“This bird turned around and went straight for the eye, did a backflip and hit me right in the eye again,” Christiaan Nyssen said.

And in 2021, a baby was killed when her mother fell during her efforts to dodge a magpie – a case that horrified the country.

Two years earlier an elderly man died of head injuries after crashing his bicycle while fleeing an attacking magpie, and in 2010 a 12-year-old boy was hit and killed by a car in similar circumstances.

Serious injuries and deaths are rare though. What is far more common is human aggression towards the birds.

In May a Victorian man was fined after killing four magpies and injuring another two so seriously they were euthanised. And almost every year, wildlife officers report finding birds pierced with arrows, shot with guns, set on fire, shackled with chains, poisoned, or mutilated.

‘Problem’ birds are also sometimes killed by authorities, and in 2021 one Sydney council conducted a general cull of the birds after a spate of incidents.

How to make peace

Animal behaviourists say the magpie is misunderstood, and there’s no need for them to be harmed. It is our fear and response to them that is dangerous.

Yes, there are a very small number of “rogue” birds which have become aggressive – radicalised by interactions with humans – says Prof Kaplan. They should be “dealt with firmly”.

But the vast majority of magpies are reasonable creatures, she insists.

The best thing to do is avoid them. Authorities often erect signs, warning of magpies in the area, and some states have even launched apps designed to track sightings of nests.

If you are swooped, don’t run, or fight back, experts advise. If you’re on a bike, get off it. Stay calm and walk quickly through the area. Shelter under an umbrella or hold your backpack over your head.

The use of protective gear is also encouraged, like sunglasses and magpie hats.

Traditionally, they have been a plastic ice-cream containers – with eyes drawn or stuck on – or a helmet laced with zip ties. In recent years though, they’ve become more elaborate. For example, contraptions rigged up with party poppers or adorned with a fake magpie.

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Facebook content may contain adverts.

But if all else fails, beg for mercy. Although authorities usually warn against feeding wild birds, Prof Kaplan suggests leaving a peace offering like a slice of bread or meat to win the magpies’ favour.

“You can make friends with magpies… they tend to be very diplomatic,” she says.

Ms Zylstra finds that prospect laughable: “Literally how… especially while they’re swooping you?”

But she agrees the birds should not be harmed and humans should learn to live in a kind of wary peace with them.

“As much as I don’t like them, they don’t deserve to die… just because they’re defending their eggs.”

Besides, magpie attacks are a character-building rite of passage, she says.

“Are you really Australian if you haven’t been swooped by a magpie?”

Related Topics

-

-

28 April 2021

-

-

-

24 November 2022

-

-

-

11 March

-