Getty Images

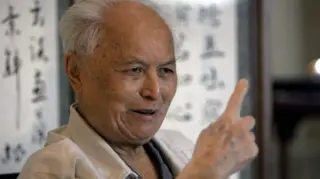

Getty ImagesIn a case being portrayed as a battle against Chinese state censorship, a test has begun in California to determine whether Stanford University is keep the journals of a major Chinese established.

The later Li Rui, a former minister to Mao Zedong’s Communist China, is the author of the memoirs.

His wife filed a lawsuit for the files to be returned to Beijing after Li’s dying in 2019. She claimed they belong to her.

Stanford rejects this. According to the report, Li, who had previously been critical of the Chinese government, gave his memoirs to the school out of fear that the Chinese Communist Party would devastate them.

The diaries, which were written between 1935 and 2018, cover much of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP ) rule. China emerged from impoverished confinement to become a key component of the global economy during those eight turbulent years.

” If]the diaries ] return to China they will be banned… China does not have a good record in permitting criticism of party leaders”, Mark Litvack, one of Stanford’s lawyers, told the BBC before the trial began.

The BBC has contacted attorneys representing Zhang Yuzhen, Mr Li’s lady, for opinion.

Mr. Li, a notable CCP number known for his liberal views, was both admired and ignored by the celebration.

In the middle of the 1950s, Mao made him one of his private secretaries because he was a young vocal cadre. But the place was shortlived.

When Li criticized Mao’s landscapes at a social gathering, he was ousted and sentenced to years in prison. He was one of the hundreds of party authorities and figures who had ties to Mao and who were vilified by the eccentric head.

Like some of them, Li returned to prominence after Mao died in 1976. He oversaw the ministry of hydroelectric power and a CCP department that selected officials for key positions. Within the party, he was allied with the more liberal, open-minded faction advocating for reform.

After his retirement, he continued to lobby the party for reform. But his unsparing, sharp-tongued criticism of leaders, including President Xi Jinping – whom he dismissed as “lowly-educated” – needled the government. His writings were censored and his books banned in China.

As a group elder, nevertheless, he continued to be treated with respect and enjoyed privileges. He was given a state death when he passed away.

Throughout, as he navigated the echelons of power, he meticulously recorded observations about party politics and key events in his diaries.

These include his account of the Tiananmen Massacre, which he witnessed from a balcony overlooking the square and labelled as “Black Weekend” in English in his diary. It is a highly sensitive issue that is rarely discussed in China.

His girl, Li Nanyang, began donating his records, including the memoirs, to Stanford’s Hoover Institution in 2014, when he was still alive.

In a 2019 interview with BBC Chinese after his death, she said this fulfilled her father’s intentions.

In China, Ms. Zhang filed a complaint against Li Nanyang, her stepdaughter, in the same year.

Getty Images

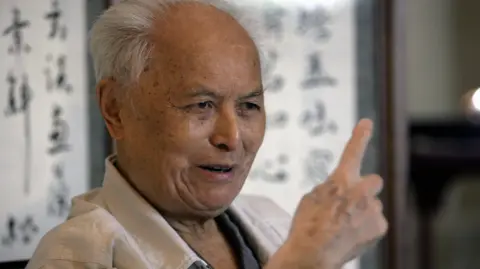

Getty ImagesAccording to reports, Ms. Zhang, who was Li Rui’s next wife, claimed that he wanted her to choose which of his records may be made public and that Stanford received them inadvertently.

The lady claimed that the memoirs contained “deeply personal and private interests” of her living with Li. She claimed that her “personal disgrace and emotional distress” were brought on by the diaries ‘ accessibility by Stanford’s people.

The journals were ordered to be delivered to Ms. Zhang by a jury in Beijing.

Stanford has rejected this decision. The school was never given a chance to defend itself, according to its lawyers, who claim that” Chinese authorities are not objective in politically charged situations like this.”

The college filed a separate petition against Ms. Zhang in the US, and the trial that started in California on Monday was the result of that suit.

Stanford is asking the California judge to grant the university’s request that the school be declared the sole proprietor of the diaries.

According to its attorneys, Li Rui wanted to give his paperwork to Stanford because he “understood that the government would seek to control his account of contemporary Chinese story” and he “feared that the materials may be destroyed.”

In order to follow Li’s hopes, Stanford has been given the right to keep copies of the journals, but it is arguing to keep the original files as well.

” Li Rui wanted his memoirs, including his classics, at Hoover”, Mr Litvack said. ” We have fought to keep them at Hoover because that’s why they are there.”