“Our generation has no expectations,” says 24-year-old Yin.

The medical student, who only wanted to share her last name, has a licence to practise, and is pursuing a graduate degree, hoping to get a job at a big hospital. But she is not sure it will help. Degrees, once highly valued in a competitive Chinese job market, have lost their sheen as graduates have outpaced jobs.

“Now, a graduate degree is worth what an undergraduate degree was some time ago. In the future, PhDs will be as good as a graduate degree is now,” Ms Yin says.

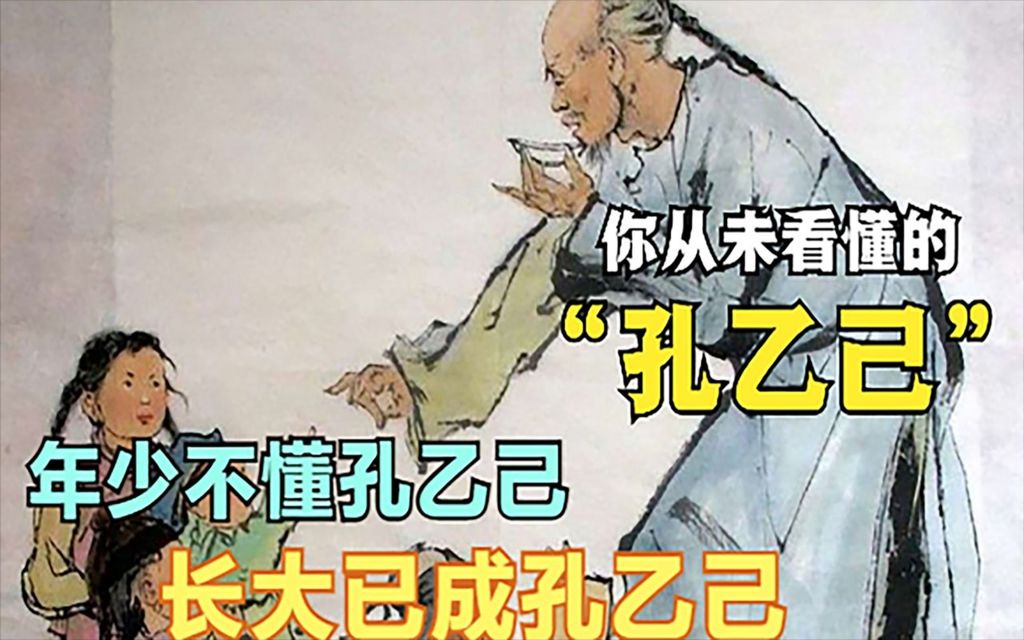

The disillusionment is echoing through young people in China, where a fifth of those between the ages of 16 and 24 are jobless, according to official figures released in May. And it’s finding expression in viral memes inspired by a famous short story from more than a century ago. The tale of Kong Yiji, a failed scholar who lived in poverty, has now become a code word for discontent among millions of graduates confronting a bleak future.

These memes – or Kong Yiji literature as they are known in Chinese – run into the hundreds, and can be found on nearly every social media platform in the country. They range from comments, drawing on literary metaphors, to whole rewrites of the tale. The latter have taken the form of an animated video and even a rap song – the last was a step too far for Beijing, which scrubbed it from the internet.

The man and the meme

Ms Yin finds the state’s reaction to the memes hypocritical.

In one commentary, state broadcaster CCTV said students should “take off the long gown”, referring to a crucial element of the story, perhaps its most abiding detail. The “long gown” worn by Kong is what divides the rich and the learned from the uneducated poor who wear “short jackets”. So CCTV’s advice, it appears, was that students should swallow their pride, discard the long gown, and find whatever jobs they can.

“They said our future would be bright and beautiful, but now we have discovered that our dreams have been shattered,” Ms Yin says, adding that until now, young Chinese had always been told that the years spent studying and chasing degrees would pay off.

For her and so many others, the similarities with Kong are striking although his story takes place in what is widely believed to be late 19th Century Qing-ruled China. Kong, we are told, failed the “keju”, a gruelling imperial exam to enter the prestigious bureaucracy. Without what was then the only channel for social mobility, Kong is forever cast to the side. His story has endured as a scathing criticism of the system – and is now resonating with yet another generation of Chinese, jobless and frustrated by an exam culture that is just as exacting.

The Kong-inspired memes first appeared on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter earlier this year.

“I thought education was a stepping-stone. But I have gradually realised that it’s a pedestal from which I can’t come down, and long-gowned Kong Yiji couldn’t take off,” one Weibo user said.

They blew up in mid-March when CCTV published their take, blaming Kong’s tragic life on his failure to adapt, and find whatever job was available. And yet it insisted that “the Kong Yiji-era has gone, and ambitious young people will never again be stuck in the long gown”.

Angry young people reacted with a flurry of posts and comments, pointing to what they saw as wrong and unjust: the mismatch among education and jobs, the lack of a safety net for the unemployed, and the shrinking options for social mobility. Some likened the CCTV response to “gaslighting”.

China changed

“If a single university student cannot find a job, perhaps he is to blame. But unemployment among undergraduates is so high. Can we blame them all for not taking off Kong Yiji’s long gown?” asked a user on the Quora-like platform Zhihu.

She was among several people who spoke of the many years Chinese students spend studying – time, they now felt, they had been cheated of, and if they gave up their dream, what was even the point of it all?

“People live like ascetics for 10 years or more to educate themselves well,” wrote another Zhihu user. “They don’t do much for fun and rarely interact with the other sex. Their families spend a lot of money, buying houses in good school districts or sending their children abroad to study.”

“A low salary is not the scariest thing. The lack of social welfare protection and opportunities to acquire new skills is,” he added.

Their comments repeatedly expose the gaping holes in China’s safety net – of its urban workers have unemployment benefits. They also reflect dawning gloom over not just their future, but their country’s.

In the words of one user: “Can someone from a humble background achieve great success? I am afraid it is rather difficult now… Wealthy people are not even in the same lane as us.”

For decades, an unspoken social contract has assured power for the party in exchange for prosperity. But now China’s economy is faltering after decades of breakneck economic growth. And young Chinese who grew up watching their parents succeed are struck by how much seems to have changed.

“When I was a child, my dad found a career and worked hard. He was confident in his future and looked forward to it,” says 25-year-old Wang Yuxi. Her own excitement at making it to graduate school has now turned to disappointment. How would she describe her prospects? “Whatever”.

“Our parents staunchly believed a good job equals success,” Ms Yin says. “Now, we have found that they experienced a period with opportunities. We no longer have those opportunities.”

China is expecting a record 11.5 million graduates this year. Already some 60% of 100-odd leading companies have reportedly said they will be hiring fewer graduates. The government is well-aware of the challenge: the growing “anxiety, disappointment and confusion of university students” may affect the economic confidence of society, an official report said back in November 2022.

While the frustration and disappointment was already visible on social media last year, Kong Yiji has lent it a fresh poignancy.

The ‘top sage’

The story was written in 1919 by Lu Xun, a Chinese literary giant often compared to Dickens and Orwell. Lu’s biting critiques of feudalism and oppression are familiar enough for them to turn into viral, even subversive memes – and yet safe enough from the censure of the Party.

How do you silence the work of a man the Party has canonised? Leader Mao Zedong called him the country’s “top sage”.

Students might complain of his difficult style, but he still “remains in the recess of the mind”, ready to strike a chord when the time right, says Eileen Cheng, a Chinese literature professor at Pomona College in the US.

“Lu was a radically independent spirit… an outspoken critic of government brutality and [he] opposed the suppression of individual voices.”

The Party, scholars say, manages Lu’s legacy by arguing that his criticism was directed at a bygone China because he had died well before the People’s Republic was founded in 1949.

But now after years of reading him as part of Communist lore, students are finally “questioning Lu Xun’s canonical status” and using his texts in subversive ways, says Professor Sebastian Veg of the School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences in Paris.

As the space for dissent in China shrinks, the legendary Lu Xun it appears, is finally breaking through.

Illustration by Davies Surya

Read more of our coverage on China