The late Shinzo Abe left an important mark on Japanese political history. As prime minister he exercised strong leadership over traditionally independent-minded bureaucrats, although the outcomes of his top-down policy renewals varied. How does Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s leadership compare?

Kishida’s leadership is a return to the traditional patterns of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) prime ministers who respect collaboration with the bureaucracy, making his policymaking incremental and colorless.

Those who admire Abe’s forceful style will find Kishida’s consensus orientation unsatisfactory. Kishida’s failure to perceive a quietly progressing breakdown of the bureaucracy is detrimental to Japanese politics.

The negative aspects of Abe’s aggressive approach toward the bureaucracy became visible toward the end of his tenure, making voters concerned about the integrity of bureaucratic behavior.

The revelation that elite bureaucrats at the powerful Ministry of Finance illicitly engaged in document tampering to defend Abe’s position in parliamentary questioning warned of the excess of political control.

Interference with appointments at the Public Prosecutors Office, which traditionally plays the leading role in investigating politicians’ scandals, raised suspicions about political corruption.

Inside the LDP, Kishida leads the Kochikai faction. This faction was founded by bureaucrats-turned-parliamentarians whom post-war prime minister Shigeru Yoshida recruited during the US occupation. It retains the tradition of working closely with the bureaucracy.

In the last two decades, the LDP’s factional politics has changed greatly. While the factional bosses have lost their material controlling tools like political funds and party endorsement, their factions’ identities have proven to be more important in keeping unity among followers.

Unlike Abe, who graduated from a private college that lacks nationwide recognition, Kishida spent his formative years as a high performer in the “examination hell.” This inclines him to be sympathetic to bureaucrats and respect their competence.

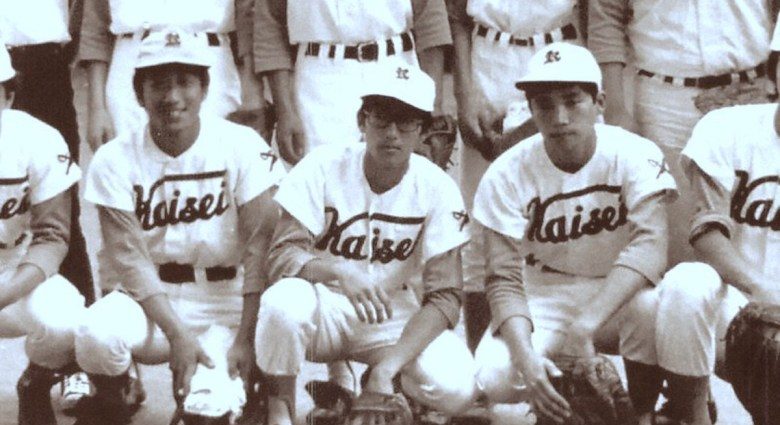

Kishida graduated from Kaisei Academy, a prestigious high school that sends many alumni to the University of Tokyo, where he unsuccessfully sat its entrance exam three times before eventually enrolling in Waseda University, a top private college.

Kishida’s consensus orientation results in his cabinet’s uninspiring policymaking. His policy programs mostly extrapolate from existing ones. His signature policy vision, a “New Form of Capitalism,” has little substance.

In step with large corporations and the economic bureaucracy, Kishida is eager to reopen nuclear power plants, but unenthusiastic about renewable energy and carbon pricing. Deterred by his party’s conservative segment, his LGBT policy is less progressive than many voters want to see.

In foreign policy, Kishida’s bold increase in the defense budget and his passive China policy appear to diverge from Kochikai’s patterns, but are based on a broad agreement across the LDP and bureaucracy and supported by public opinion. Kishida is not interested in following in Abe’s footsteps to turn Japan into an active player in the Indo-Pacific’s strategic balance of power. But he fails to take specific steps for nuclear disarmament despite his strong support for it.

From a broader view, Kishida’s failure to respond to an institutional crisis quietly hitting Japanese politics is more harmful than his incrementalist programs. The proudest achievement of Japan’s modern politics — the bureaucracy — now faces an existential threat. Abe’s attacks considerably damaged bureaucrats’ morale and confidence. But a different illness now infiltrates the bureaucracy.

Japanese ministries are becoming unable to regenerate themselves due to a shortage of competent personnel that their poor work environments cause. A combination of around-the-clock work, inflexible staffing, delayed digitization and conventional bottom-up decision-making compels Japanese administrators to work for abnormally long hours.

Tightened post-retirement regulations reduce the financial rewards that bureaucrats can expect. There is a major exodus of bureaucrats in their 20s and 30s, who feel the most suffocated by seniority-based promotion.

New graduates from top universities now prefer foreign financial institutions and consulting firms to the civil service. Becoming an elite administrator is no longer a dream job for Japanese youth.

At the same time that Japan faces an endless list of difficult policy problems, the main institutional infrastructure intended to assist in political planning and decision-making is falling apart because of recruitment and retention failures.

The problem is not Kishida’s personal creation. Like many other structural problems in Japanese society, it has occurred because of the collective inability of Japanese leaders — who are uniformly older males — to prioritize the needs of younger generations due to their nostalgia and complacency.

Now that the problem cannot be put off any longer, Kishida’s inaction will likely be counted as a fatal error in the future appraisal of his premiership.

Ko Mishima is a professor of political science at East Stroudsburg University, Pennsylvania.

This article was originally published by East Asia Forum and is republished by Asia Times under a Creative Commons license.