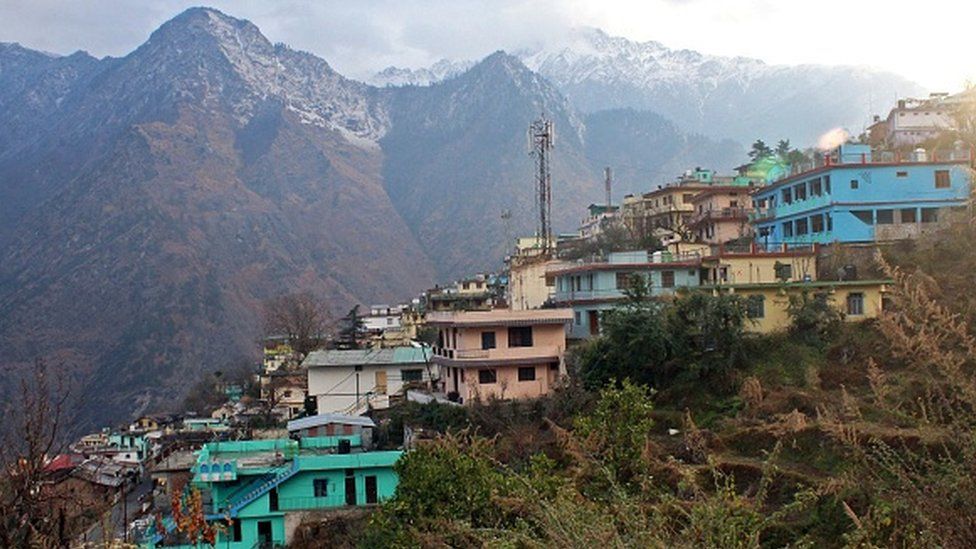

Hundreds of people have been evacuated from Joshimath, a Himalayan town which has been slowly sinking into the ground in India. As residents waited in uncertainty, the BBC’s Vineet Khare spoke to experts to understand if the town could be saved.

Pushkar Singh Dhami, chief minister of Uttarakhand state where Joshimath is located, said that around 25% of the town’s area had been affected by the subsidence.

Joshimath, with 25,000 residents, has around 4,500 buildings spread over 2.5 sq km (0.96 sq miles). More than 800 buildings have developed cracks, and authorities have been demolishing the unsafe ones.

“It doesn’t look like the subsiding areas of Joshimath – which comprise settlements, houses and constructions – will survive,” says geologist Dr SP Sati.

“There are no obstacles down the slope to prevent the subsidence, and there should have been multiple obstacles,” he says, referring to the lack of green cover in the area.

Joshimath was built on the debris of a landslide triggered by an earthquake, and is located in a tremor-prone zone. It frequently witnesses landslides, which have weakened the soil.

The subsidence will continue until a new lower level is reached, warns CP Rajendran, a geoscientist and adjunct professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies.

“It will stabilise eventually, but by then many of the buildings will get damaged,” he says.

Residents are also worried that rain or snow in the days and weeks ahead could worsen the situation.

Experts say the present crisis has been caused by several factors including years of unplanned construction, hydropower projects and the lack of a proper drainage system.

Back in 1976, a government report had mooted restrictions on heavy construction work in Joshimath, saying that it should only be allowed after examining the “load-bearing capacity of the soil”.

The report had also suggested constructing proper drainage and sewage systems, and installing concrete cement blocks to check erosion.

Last year, a report by a government panel echoed many of these recommendations, including building a “well-planned drainage system”.

But activists have long complained that these haven’t been implemented.

Local anger is directed at a top Indian power company, the government-owned NTPC Ltd, whose ongoing Tapovan Vishnugad hydro power project, they allege, is tunnelling through the fragile ecosystem.

“The company is responsible for the damage to the historic, cultural town of Joshimath, and it should compensate residents,” says Atul Sati, the convenor of a group who has been holding protests to save the town.

NTPC has denied the allegations. In a statement, it said its tunnel does not pass under the town and that it is at a “horizontal distance of over a kilometre from the outer boundary of Joshimath town”.

Federal power minister RK Singh has dismissed links between the power plant and the town’s condition.

“Nothing happened to the village nearby and the villages above the project, and nothing happened to all the villages in that 15km stretch,” he said in a recent interview.

The federal government’s high-profile Char Dham road project, which aims to widen existing roads connecting four Hindu pilgrimage sites, has also drawn criticism. Work on a bypass road that would have passed through Joshimath has been stopped after protests.

“You cannot have a freeway like the Autobahn [Germany’s federal highway system] in Europe built in the Himalayas,” Mr Rajendran says.

Administrators say these allegations could impact “the inflow of tourists” to the area and damage the local economy.

“We should ground our claims in science,” says Himanshu Khurana, the magistrate of Chamoli district, where Joshimath is located.

“The Himalayas are there in China, Nepal, in Pakistan, spread across so many states in India. Why only target Uttarakhand?” asks R Meenakshi Sundaram, secretary to Uttarakhand’s chief minister.

“If the Himalayas are fragile, no development activity should take place in any of these countries and in other states,” he adds.

Some have also advised caution while deciding the future of the town, which is close to India’s border with China. Dr Suvrokamal Dutta, an economic and foreign policy expert allied with the governing Bharatiya Janata Party, says that stopping development activity in border areas “would be a very cynical and strategically disastrous thing to do, taking into account India’s security and strategic concerns due to the China factor”.

Some experts still believe the situation is salvageable.

Dr Swapnamita Vaideswaran, a geologist at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, says that the immediate need is to rehabilitate the worst-affected people. In the long term, she says, there will need to be “a new planned town” which has stricter building rules.

Others disagree.

“This valley seems to be more unstable, more unreliable for human living and construction than your average Himalayan valley,” says Dr Jeffrey S. Kargel, senior geologist at Planetary Science Institute in the US.

“It should be a national park. Let people come in for short periods of time to enjoy nature and get out,” he suggests.

He refers to a “similar cracking” that occurred near the Pakistani town of Aliabad in 2010. A landslide caused debris to block the river Hunza, which in turn prevented water from flowing downstream and created what is now referred to as the Attabad lake.

The BBC reported that thousands had been displaced by the rising water levels in Attabad. The site is now a tourist spot.

Read more India stories from the BBC: