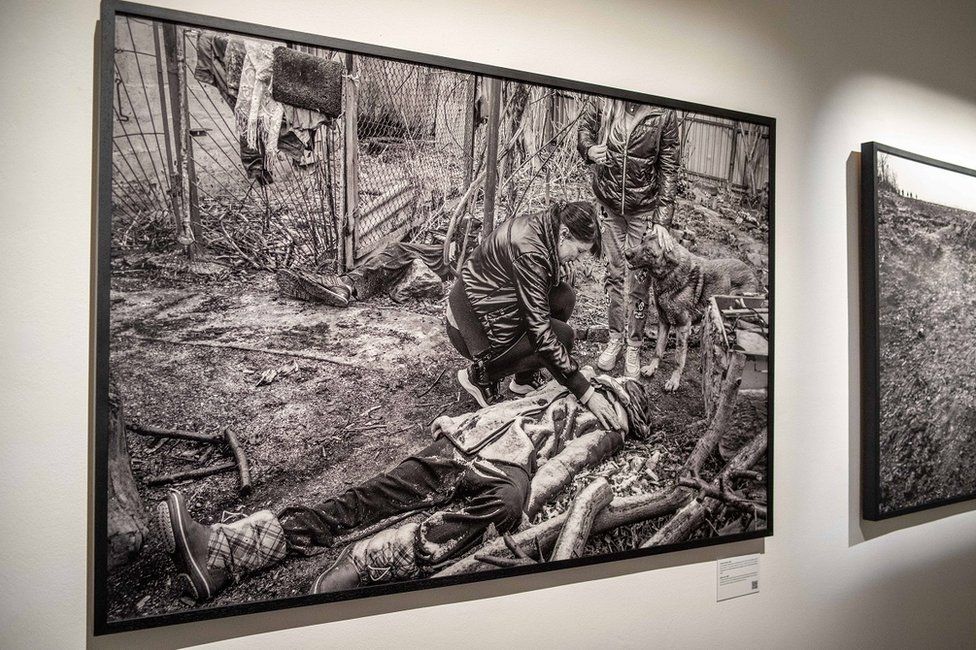

A woman has just discovered the bodies of her husband and brother in her garden in Bucha, a suburb of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv.

The bodies are dusted with frost. She lays one hand on her brother, while the fingers of her other hand touch her mouth.

There are two more human hands almost perfectly arranged in the frame, of someone whose face cannot be seen – one resting on the head of a dog, the other playing nervously with her blonde hair.

It presents an unexpectedly peaceful moment, arranged with the near-perfect balance of a classical painting. Except it’s not – it’s a photo from the aftermath of the massacre of civilians in Bucha, taken by the renowned photojournalist James Nachtwey.

“Hands and eyes. I’m concentrating always on hands and eyes. And the detail of the dog. You actually seem to see sympathy in the face of the dog,” says Mr Nachtwey, who has brought his retrospective exhibition Memoria to Bangkok, the only place it is being shown in Asia.

The collection has 126 photographs from some of the worst conflicts and disasters of our times – from Central America in the 1980s to the ongoing war in Ukraine.

A very private, softly-spoken man who prefers to let his images speak for themselves, Mr Nachtwey agreed to be interviewed in Bangkok about his approach to photojournalism, and about the state of the profession in the digital age.

Now 75 years old, Mr Nachtwey just missed being part of the Vietnam War generation of photojournalists, when the profession reached the peak of its influence.

The searing images from that conflict, from photographers like Philip Jones-Griffiths, Don McCullin and Tim Page, helped swing public opinion against involvement in the conflict and force the US withdrawal from it.

But Mr Nachtwey is arguably the greatest of the generation that followed.

Five-times winner of the Robert Capa Gold Medal for courageous overseas photographic reporting, his images are known for both their brutal immediacy and their stunning composition and lighting, rendering his subjects with humanity and warmth.

Even in an information landscape dominated today by video and instant, digital distribution, the greatest still photographs have a unique power, in the split-second moments they capture, to distil the essential themes of a news story, to freeze the action, to invite reflection.

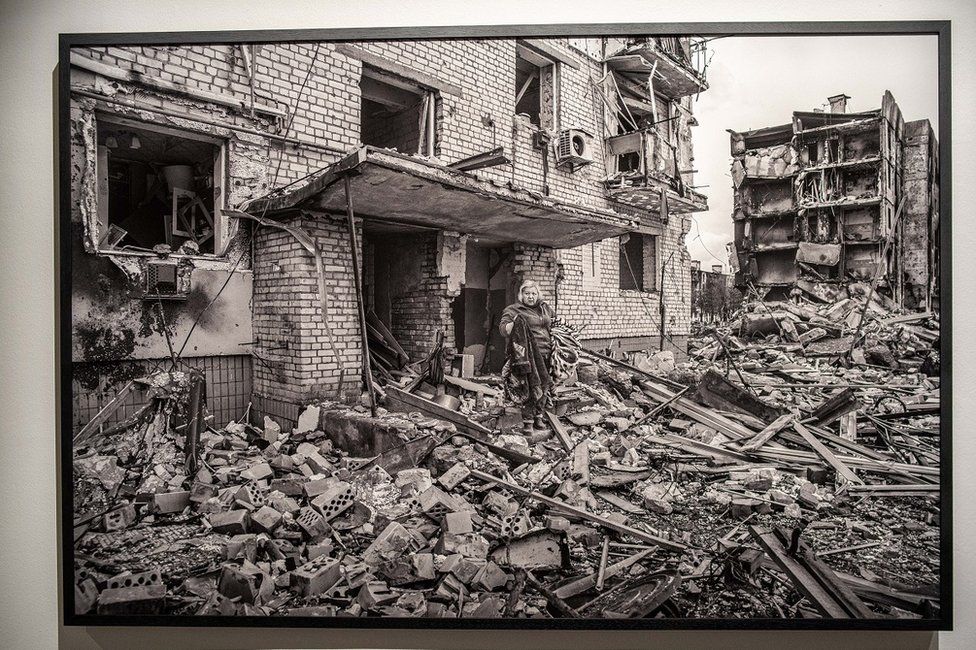

As we looked at a striking photo of a woman with blonde hair emerging from a smashed apartment block on the outskirts of Kyiv in April 2022, just after Russian forces had withdrawn, I asked him how he went about capturing such well-composed shots.

The woman is clutching blankets she has retrieved from her home, and looks casually at the camera as though performing a normal domestic chore, with a vast jumble of pulverised rubble behind her.

Did he just “spray and pray”, hoping to get one good image out of hundreds? A feasible technique in the age of digital cameras, which can take dozens of shots a second.

“Prayer does not enter into it,” he says. “It’s really about years of training, applying what I’ve learned, being persistent. In any given situation, it’s highly unlikely that I’ll make a strong, significant image. But the only way I can ever succeed in doing that is to simply throw myself into the situation. And just keep shooting, and follow my instincts and my intuition, and find a place where a picture might happen.”

Most of the images in Memoria are black-and-white. But that’s not always his preference, he says.

“Early on in my career, before I established myself, I didn’t have much choice. If the editors asked me to do colour then I did colour, and I always tried to use colour in a way so that it didn’t become the subject of the picture. Colour is a very powerful phenomenon. So powerful that it can become the subject, so I tried to keep it under control.”

In some images, though, the colour really stands out. An early photograph from the El Salvador civil war shows a military helicopter evacuating an injured soldier. But it is the three little girls crouching behind a tree in the foreground, their dresses of white, pink and pastel blue standing out in the orange dust cloud, who give the image its haunting loveliness.

Most of Mr Nachtwey’s career has been in the era of film. Digital photography, he says, is “more time consuming”.

“In the days of film, I’d shoot my rolls of film, and that was it. I would write my captions, label the rolls and then I would have an evening to network and talk with people, get information to figure out what I was going to do the next day. Now I have to download all the memory cards, back everything up, do an initial edit.”

We are looking at his photographs from Afghanistan. Incredibly strong, stark images, not taken recently but in 1996, from when Kabul was reduced to a shattered moonscape by the battles between competing warlords.

In one, a woman in a light-coloured burqa seems to float like a ghost through the black ruins. In another a woman on her knees reaches out with a ringed hand to hold the rough-hewn gravestone of her brother, killed by a Taliban rocket. She is surrounded by dozens more of these hastily-dug graves.

“This is the final stage of the Afghan Civil War, when Kabul was surrounded and besieged by the Taliban,” he recalls. “They were shelling and rocketing the city every day. The NGOs had left, with the exception of the ICRC. Virtually all the foreign journalists had left. The editor-in-chief I was working with at that time, he had no interest in the story. But I did.”

He has arranged this section right next to the dramatic shots he took of the 9/11 attacks in New York, to make the connection.

“We are in a totally interconnected world. The siege of Kabul was one of the last battles of the 20th Century. And once the Taliban took over, it set the stage for the wars of the 21st Century. Today you can’t pretend that things that happen on one side of the world will not affect you. Because in this day and age, they invariably do.”

I put to him a point made by his famous colleague Don McCullin, 12 years his senior, that digital photography is so easily manipulated that it can no longer be trusted.

“I don’t agree with that assessment,” Mr Nachtwey says. “The credibility of the person who’s making the picture and putting it out is very important. So, yes, some people might manipulate falsely a digital image, but they could do that with film as well in the darkroom.”

But we live in a sceptical age, where so many no longer believe in the impartiality of the established media which has given Nachtwey his greatest exposure. Does that trouble him?

“I think it’s fine to be asked if we have agendas and biases, I think that’s a very good question. And I think we should be ready with a good answer. We should have thought about that and understood it ourselves. I’ve rarely covered a war where I don’t have a very strong opinion about who’s the aggressor and who’s the victim, and where right and wrong plays out. That doesn’t mean I’m going to create propaganda for anyone, it doesn’t mean I’m going to falsify my images.”

Is the heroic age of the photojournalist, though, coming to an end? Especially at a time when people are bombarded daily by a tsunami of digital images, and when the first, and often most dramatic, photos of an event are usually taken by citizen journalists with their phones?

I suggested that the heyday of photojournalists was probably the pre-digital era of the Sunday colour supplements of newspapers, and influential, image-rich magazines like Time, where millions would see powerful photos from the world’s trouble spots for the first and only time.

But Mr Nachtwey remains an optimist – about his profession, and about humanity, whose darkest sides he has spent his life chronicling.

“The fact that people are using their phones in situations where journalists might not be present is I think very useful. Journalists can’t be everywhere. But the two are not mutually exclusive. We still need trained journalists and photographers who are not just making random shots, who were actually trained and have insight, experience, and talent. Because that counts for something. It’s not only the message – it’s the quality of the message, which speaks to people.”

At the far end of the exhibition is a photograph, printed very large, of a young Vietnamese woman damaged from birth by the effects of the chemical herbicide Agent Orange.

Her mother holds up her thin arms, for exercise, in an almost balletic pose. Behind her lies her sister, similarly afflicted, and the rough texture of her simple home. Your eye is drawn to the dazzling, filigree lace around the neck of the young woman. And the closed-eyes, seraphic expression on her face.

It is an achingly beautiful image, which for just a moment, makes us forget all the suffering that lies behind it.

Related Topics

-

-

21 February 2019

-

-

-

22 November 2021

-