The deletion of a chapter on Mughal rulers from Indian school textbooks has reignited a debate on how history should be taught to schoolchildren.

The discussion was sparked by the publication of a new set of textbooks by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), an autonomous organisation under the federal education ministry. The NCERT oversees syllabus changes and textbook content for children taking exams under the government-run Central Board of Secondary Education.

Other changes include the removal of some references to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi and the 2002 riots in Gujarat state.

NCERT has said that the changes, which were first announced last year as part of a syllabus “rationalisation” exercise, wouldn’t affect knowledge but instead reduce the load on children after the Covid-19 pandemic.

But critics argue that the omissions are worrying and will affect the students’ understanding of their country.

They are particularly alarmed at the removal of references to the Mughal dynasty and accuse the NCERT of erasing portions of history that Hindu right-wing groups have campaigned against for years.

Many right-wing activists and historians view the Mughals – who ruled large swathes of the Indian subcontinent for centuries – as foreign invaders who plundered Indian lands and corrupted the country’s Hindu civilisation.

“Students are learning about our nation’s history in a deeply divided time. By removing what is uncomfortable or seen as inconvenient we are not encouraging them to think critically,” says Hilal Ahmed, who works on political Islam and teaches at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies.

Supporters of the exercise argue that some degree of course correction in school history textbooks is necessary because these books gave too much importance to Muslim rulers.

“The Mughal rule was one of the bloodiest periods in Indian history,” says Makhan Lal, a historian and academic who has written many chapters for NCERT textbooks.

“Can’t we write more about Vijay Nagar empire or the Cholas or the Pandyas instead?” he asks, referring to Hindu dynasties that ruled southern India.

Others, however, say this is an oversimplified and reductive understanding of India’s syncretic past.

“What is happening now is a suggestion that the Mughals were peculiarly violent – when in fact violence was part of kingship as an institution everywhere – and that they saw themselves primarily as Muslims, determined to torment Hindus,” says historian and author Manu S Pillai.

“The record, however, is more complicated,” he adds.

NCERT director Dinesh Saklani has called the debate around the curriculum “unnecessary” and clarified that the history of Mughals is still taught to schoolchildren. The BBC reached out to Mr Saklani for comment but he said he was no longer available for media queries.

Revisions to the history curriculum are not new in India – textbooks have been revised in the past under different governments.

Mr Ahmed says that textbook review is also advocated by scholars to strike the right balance between content and learning outcomes. “History never ends, it’s forever unfinished and unresolved, but history textbooks must – and that’s why they are constantly reviewed.”

But he adds that this should not come at the cost of a larger pursuit of knowledge.

The current deletions, Mr Ahmed says, throw open larger pedagogical issues of withholding information without any sense of the tensions and contradictions they embody. That’s because history, he adds, is not just about rulers. It goes beyond dynasties and battles to look at administration, governance, and culture of a time. It’s a framework through which a society understands itself.

“So when you remove something arbitrarily, you strip it of its context, making it distortive,” Prof Ahmed says.

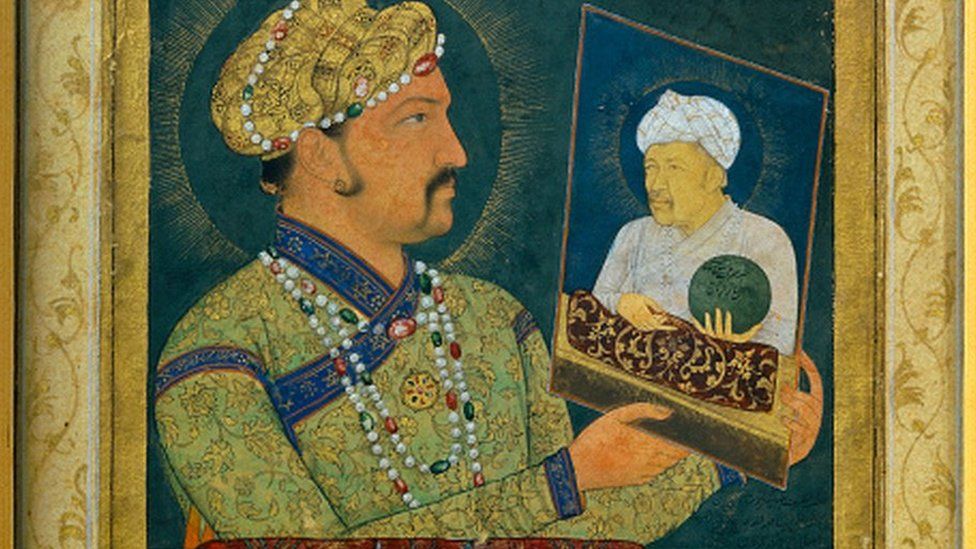

The chapter that was removed appeared in Class 12 textbooks: Kings and Chronicles: The Mughal Courts.

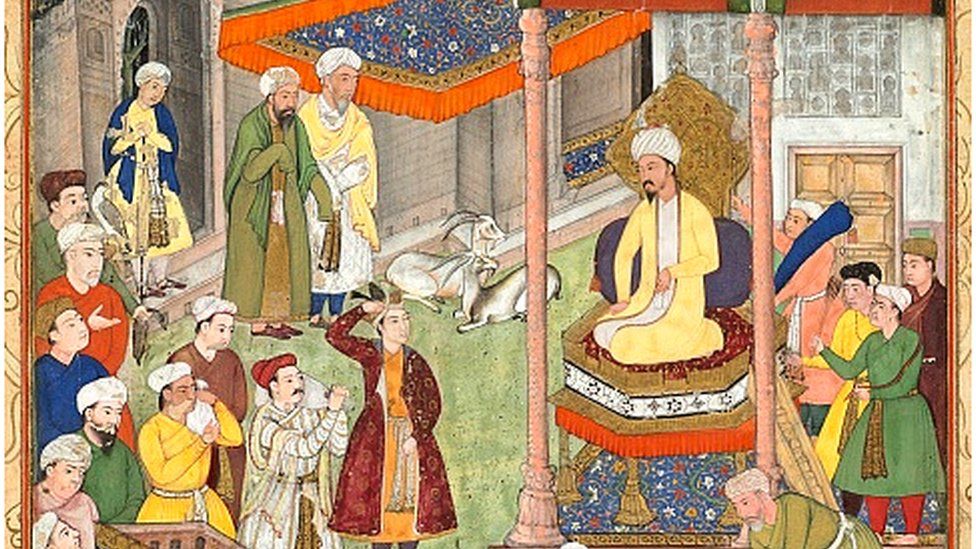

The 30-page text traces the workings of Mughal courts. Most of this was documented in lengthy historical accounts commissioned by Mughal emperors. The chapter goes on to illustrate how these “Mughal chronicles” presented the “empire as comprising many different ethnic and religious communities – Hindus, Jains, Zoroastrians and Muslims”.

Removing the chapter was justified, says Mr Lal, as it “does not have anything of historical value”.

“After all, it’s just one chapter – it’s not like Mughal history has been entirely omitted from the curriculum.”

He adds that Indian textbooks have long understated the brutality of Mughal rule, and have given them disproportionate prominence in comparison with Hindu kings. These so-called distortions, he says, have led to decades of shame around ancient Indian culture and values.

“But Indians are now reckoning with their ancient past again,” he says.

While history is not necessarily some kind of competition, Mr Pillai says that emotional propositions such as these do end up acquiring a hold in politics and public consciousness.

“There is this stress on a Hindu history of India, consciously lumping together Hindu figures on one side, and the big, bad Mughals on the other.”

But brutality, Mr Pillai adds, was not a quality exclusive to the Mughals – kings in general were violent people, and violence was a corollary to power well into the 19th Century.

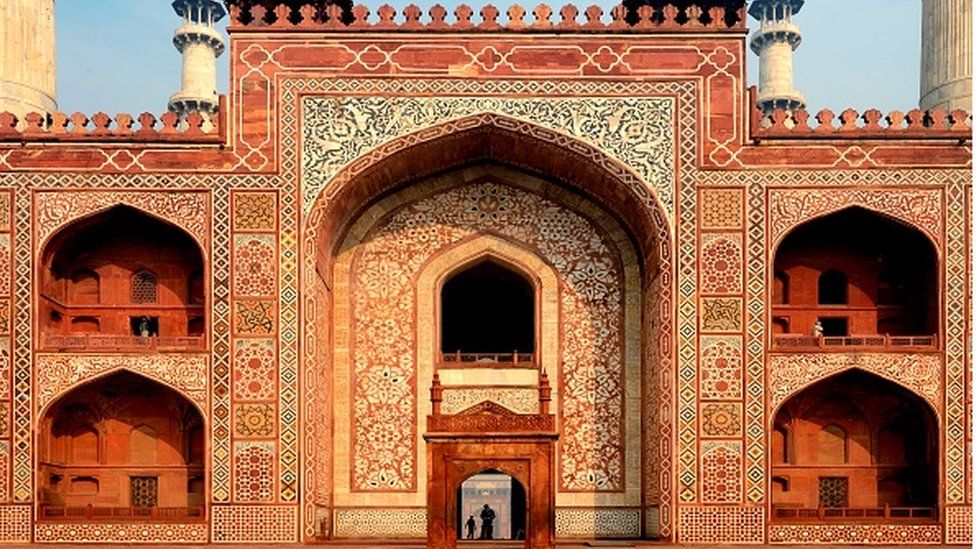

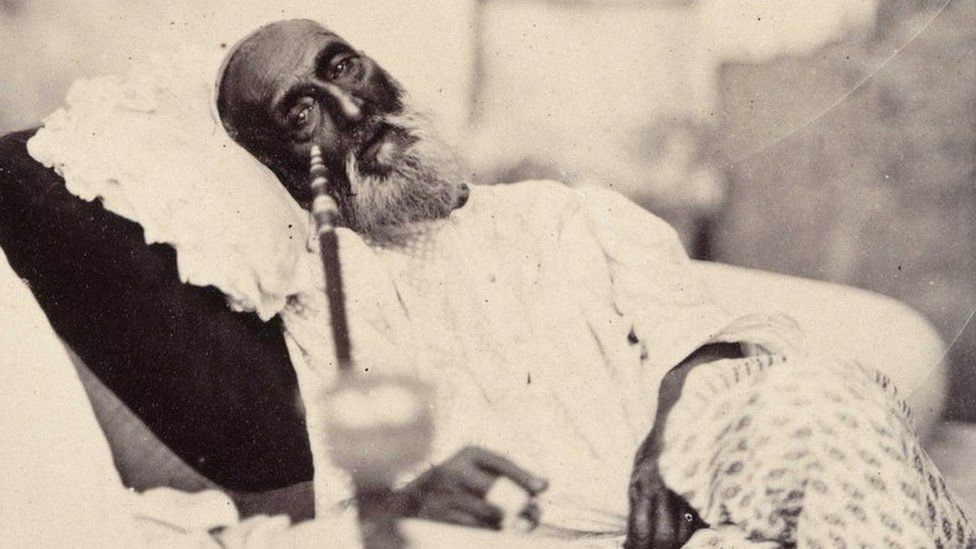

Besides, Mr Pillai says that Mughals also dominate popular imagination because of just how recent they are as well as the cultural importance they enjoyed even after their reign. To put that in perspective – the last Mughal emperor was toppled just about a decade before Gandhi was born; and earlier Indian nationalists like Dadabhai Naoroji grew into adulthood while the emperor was still around.

So we know a lot more about the Mughals, he says, simply because they were more recent – and records of their time exist in great abundance compared with, say, the Cholas who dissolved by the 13th Century.

“Perhaps it is these complexities that students should read about, instead of entirely erasing segments from textbooks,” Mr Pillai adds.

Mr Ahmed says it is ironic that a colonial view of Indian history where ancient is seen as a Hindu past and medieval is seen as a Muslim one is being reiterated by some. “You are reducing India’s overlapping cultures and religions into a mere insider vs outsider debate, when the past is actually a lot more complicated,” he says.

He adds that if key portions of history are removed this arbitrarily, then there would be “a void” in formal education.

“And it would result in a learning of a very different kind.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

-

-

19 February 2022

-

-

-

8 November 2017

-