India is making a second stage in its search for important vitamins that might be hidden in the ocean’s depths and that might be the catalyst for a cleaner future.

In the face of fiercer competition between big international power to secure crucial nutrients, the nation, which now holds two deep-sea investigation licenses in the Indian Ocean, has applied for two more.

Countries including China, Russia and India are vying to achieve the large deposits of metal resources- chromium, nickel, copper, iron- that lie thousands of metres below the surface of oceans. These are used to generate renewable energy sources like solar and wind power, electric vehicles, and cell technology needed to combat climate change.

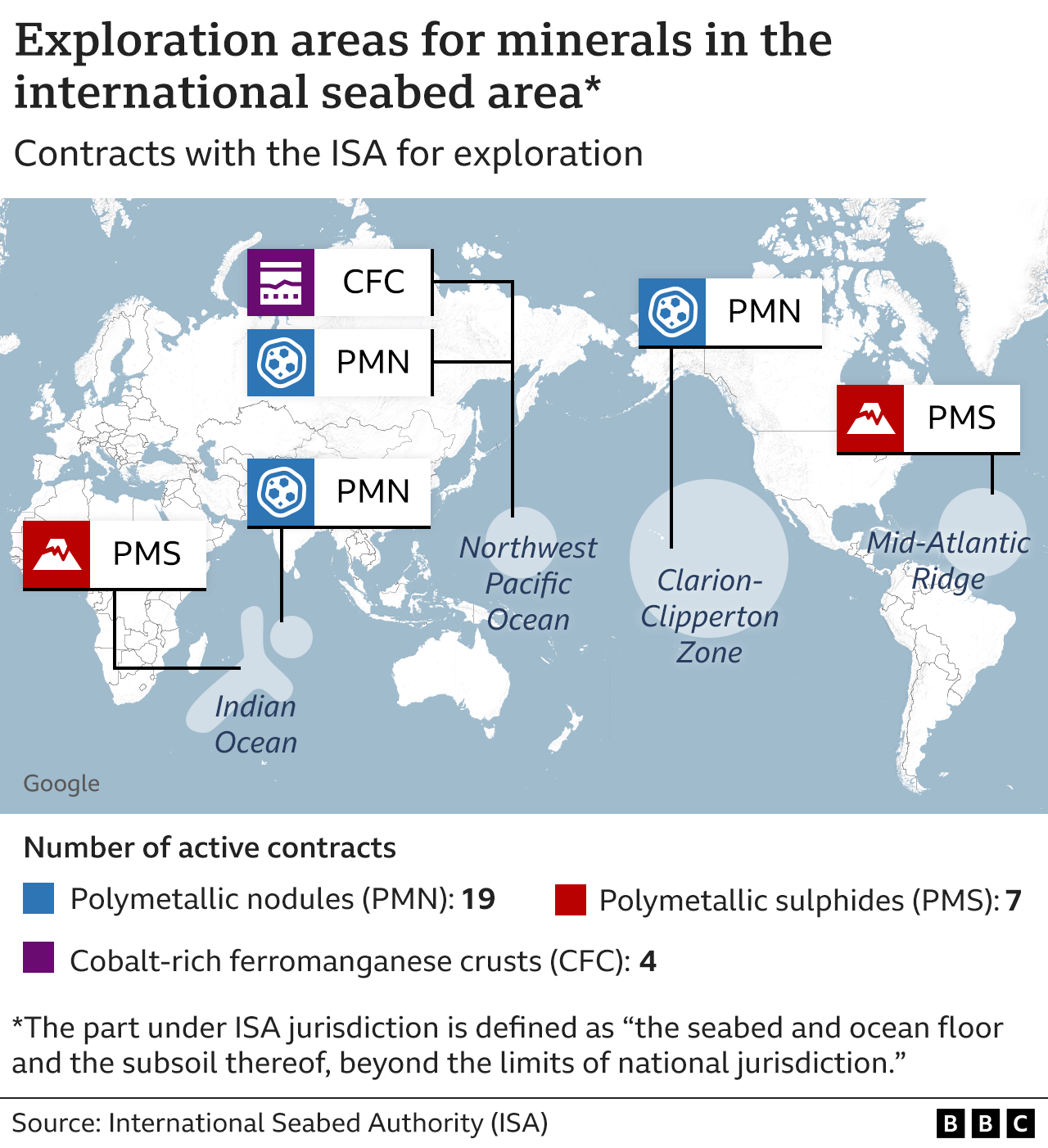

The UN- affiliated International Seabed Authority ( ISA ) has issued 31 exploration licences so far, of which 30 are active. This year, its member states are meeting in Jamaica to discuss rules for distributing mine licenses.

If the ISA approves India’s fresh software, its licence matter may be similar to that of Russia and one less than China.

In the Carlsberg Ridge in the Central Indian Ocean, one of India’s software aims to find magnetite pyrite, or chimney-like hills close to thermal holes containing copper, zinc, silver, and gold.

A list of comments and questions about this has been provided to the American government by the ISA’s lawful and technical committee, according to a document that the BBC saw.

The committee has noted that another unknown land has requested the bottom area be included in their lengthy continental shelf and asked India for a response in response to the various application, which is to examine the cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts of the Afanasy-Nikitin Seamount in the Central Indian Ocean.

Unquestionably, regardless of the results of the applications, one thing is certain: India does not want to lose ground in the search for precious minerals from the oceans ‘ bottom.

The Indian Ocean offers enormous potential reserves, and its expanse has spurred the government of India to expand its scientific exploration of the ocean’s depths, according to Nathan Picarsic, co-founder of Horizon Advisory, a US-based geopolitical and supply chain intelligence provider.

In the Indian Ocean ridge area, India, China, Germany, and South Korea already have exploration licenses for polymetallic sulphides.

The Indian National Institute of Ocean Technology tested its mining machine in the central Indian Ocean basin in 2022 at a depth of 5, 270m, and found some polymetallic nodules ( potato-shaped rocks that are abundant in manganese, cobalt, nickel, and copper ) on the seafloor.

India’s earth sciences ministry did not respond to the BBC’s questions on the country’s deep- sea mining plans.

India may be trying to convey that it is a powerhouse in its own right, one that is not rivalled in its own backyard, and that it is not lagging behind China when it comes to the deep sea, says Pradeep Singh, a researcher at the Research Institute for Sustainability in Potsdam, Germany.

The US is not a part of the international water race because it has not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the treaty that gave rise to the establishment of the ISA. Instead, it wants to process minerals mined by its allies from international waters and source them from its domestic seabed.

Deep seabed exploration is supported by claims that land-based mining has almost reached its limit, leading to poor production, and that many of the region’s mineral sources are rifracked by conflict or environmental issues.

However, environmental activists claim that the deep seabed is the last frontier on earth that is largely unstudied and unprotected from human activity, and that mining there could result in irreparable harm, no matter how urgent the need may be.

Given what they claim is a lack of information about the marine ecosystems in those depths, around 20 nations, including the UK, Germany, Brazil, and Canada, are also pressing for a halt or a temporary pause in deep-sea mining.

According to the World Bank, the demand for clean energy technologies will need to be met by 2050, which means that the extraction of crucial minerals will need to increase fivefold.

India wants to increase its renewable energy capacity to 500 gigawatts by 2030, and it wants to meet 50 % of its energy needs by then, with the long-term goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2070.

Experts claim that India will need to obtain crucial minerals from all sources, including the deep seafloor, to achieve these goals.

Currently, a few countries dominate the production of critical minerals on land. Chile is the top producer of copper, while Australia is a major producer of lithium. In China, graphite and rare earths are primarily produced (used in smartphones and computers ).

However, China’s dominance of these minerals ‘ processing before they enter the supply chain raises geopolitical issues.

China, which has developed processing methods and expertise over the years, currently controls almost 60 % of all processed lithium and manganese, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, and 70 % of the refined supply of natural graphite and dysprosium.

Moreover, Beijing has banned the export of some of its processing technologies.

At a crucial summit on minerals and clean energy in August 2023, US energy secretary Jennifer Granholm said,” We are up against a dominant supplier that is willing to use market power for political gain.”

The US and a number of western nations created the Minerals Security Partnership in 2022 to catalyze “investment in responsible critical minerals supply chains.” India is now a member.

India and Russia have also agreed to develop deep-sea mining technologies.

According to Mr. Picarsic,” the confluence of rising geopolitical tensions and the energy transition is speeding up the scramble to extract, process, and use critical minerals.”

Read more BBC stories about India: