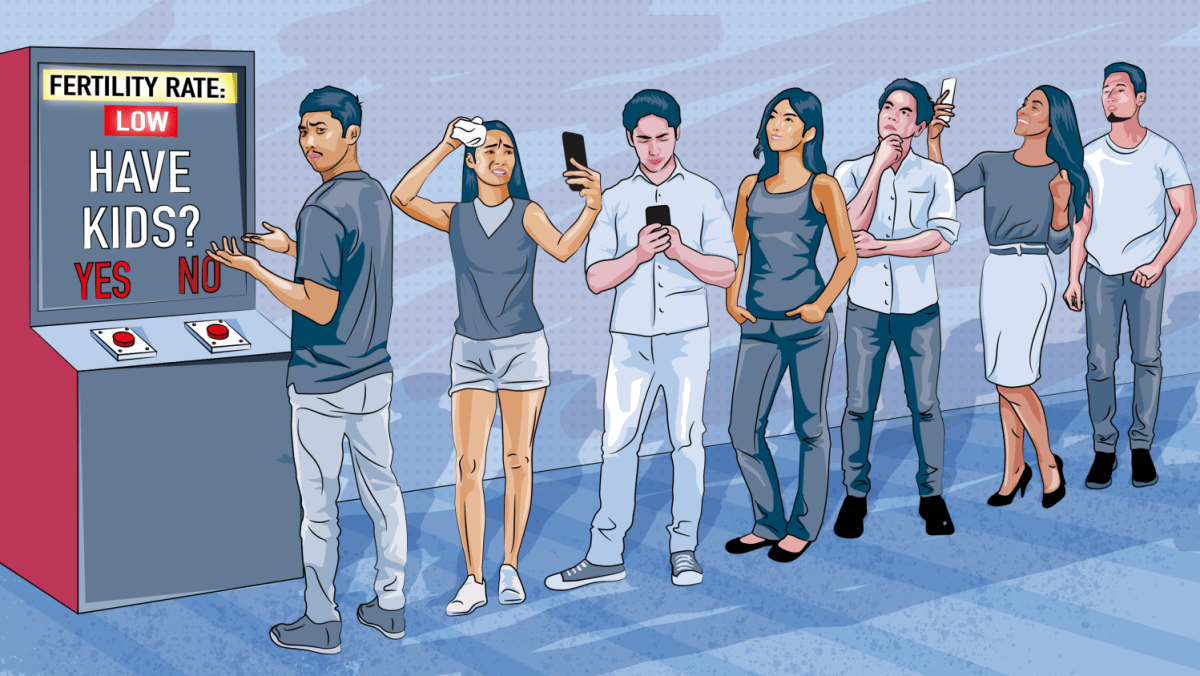

CHILDREN: “NOT REALLY VERY GOOD INVESTMENTS”?

The increasing cost of raising children – including accoutrements such as a S$1.4 billion tuition industry – comes in tandem with what Asst Prof Tan referred to as a changing “generational contract”.

Today, children are not really expected to work and contribute to household expenses, so “it’s no longer a system where (they) necessarily repay their parents because they’re grateful for their upbringing”, she said. Instead of depending on their children to provide for them, people now look to the healthcare system and their own savings.

“That means that if I’m a very rational person and I only value children from a comfort perspective, actually children nowadays are not really very good investments,” the sociologist added. “In fact, they’re a net drain.”

Camille Tan, 28, and her partner Jeryl, who only wanted to be known by his first name, disagreed with this perception of children. “If you want children, you shouldn’t see them as an investment for retirement,” she said, describing such thoughts as selfish.

The couple have dated for close to two years and do not intend to have children if they get married – a choice which left Ms Tan’s parents “quite upset” and Jeryl’s “a bit bummed”.

In YouGov’s survey, younger Singaporeans appeared to feel more pressure to have children from their peers, family and social groups. Among respondents aged below 35, 33 per cent agreed with this statement, compared with 18 per cent of those aged 35 and older.

“I think a lot of parents are very worried, (thinking) ‘What if you don’t have children and in future how are you going to take care of yourself?’,” said Ms Tan. “But that is something that I cannot agree on … It’s your job to be financially ready to take care of yourself in the future. So, I think it’s a very unfair mindset.”

Should they come to regret their decision, the couple remains open to adoption. But there are others like 39-year-old Jasmine Gunaratnam who said she has “never enjoyed the company of children”.

While she supports parenthood and pro-natalist policies from a societal standpoint, the senior director, who works in insurance, was so set in her convictions that she started thinking about how to provide for her own retirement when she was just 13 years old.

Going through school, she questioned why she felt this way, and wondered if there was something wrong with her. “Why am I not like the others, how come I don’t think about marriage? Or why don’t I care about things like having a family or playing with little baby dolls, or all these expected maternal feelings?” said Ms Gunaratnam, who has been with her husband for 18 years.

Though she has since faced many questions on whether she might rue not having children in the future, her candid answers often stop her inquisitors in their tracks. “It (becomes) quite clear to them – if you don’t enjoy children, then it’s not good for a child where a parent doesn’t enjoy their company.”

Alex Law, 38, who has been married for five years, concurred. “If you don’t truly love kids, I don’t think there’s a need for you to bring another life to this world. I think there’s a lot more purpose to being a human or a person on Earth,” he said.

The project manager in an interior design firm travels often with his wife, doing “pretty much everything” his friends can’t do, he joked. For his peers who are parents, vacations are limited to school holiday periods; Mr Law claimed that many of them who had babies right after marriage regretted not waiting a few more years.

“Me and my wife, we both are people that know exactly what we want in life. We have a bucket list to complete, and kids are just not part of the plan. At least not for now,” he said.

“People will say I am selfish, and I agree. I am selfish, I want my life for myself.

“I’ve got nothing against kids … I know I can be a good father if I have one. But the question is, why do I need to have a kid? And if I cannot answer that, I don’t think it’s right to have a kid born into this world.”

The YouGov poll found that just 14 per cent of respondents aged below 35 believed that couples who can have children but choose not to were selfish. A higher proportion – 23 per cent – of older respondents aged 35 and above agreed with the statement.