And it don’t get money, don’t get popularity

Don’t have no credit cards to drive this train

, – Huey Lewis and the Information

” What’s so awful about depreciation”? President Xi Jinping said, according to the Wall Street Journal. ” Don’t people like it when things are cheaper”?

This ( possibly apocryphal ) nugget has been popular on social media and in the media as fears of Japanification have once more piqued the imaginations of even highly educated economists and pundits.

As President Xi has but evidently demonstrated level financial knowledge, old tropes and buzzwords are being flung with gleeful abandon. These include balance sheet recession, negative spiral, lost decade.  ,

Or has he? Han Feizi even asks the same problem,” What’s so awful about deflation”? and may go so far as to say,” People surely like it when items are cheaper”!

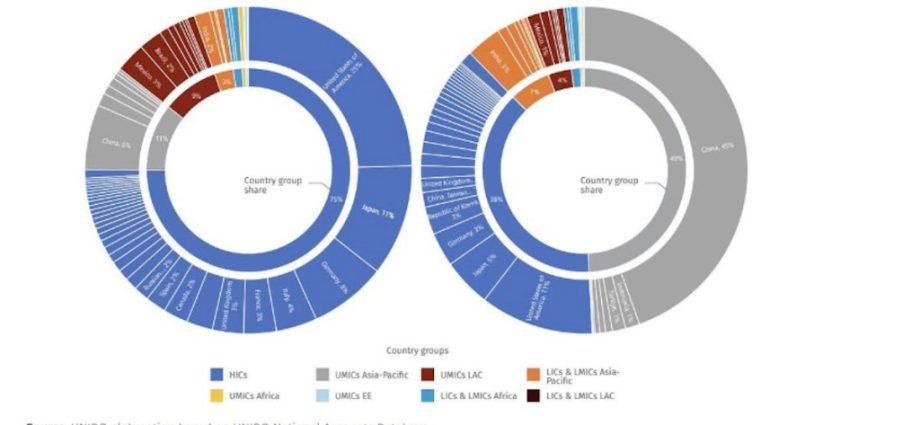

Every economist ought to be asking this question as China continues to expand its manufacturing sector, which, according to the UN, is on track to account for 45 % of the world’s total by 2030 (up from 30 % in 2022 ).

No, China is no turning Japanese. Depreciation in China’s event is no equivalent to what Japan saw in the mid-1990s, but is, in reality, its general reverse.

Japan’s recession was brought on by a bad demand shock, which caused its bubble economy to burst. At the time, Japan was the world’s most expensive business, topping the Economics ‘ Big Mac index, among other measures. The desire curve was shifted in by the bubble’s burst, leading to lower overall demand and lower prices.

Due to a good supply shock, China’s current deflation is the result of credit being diverted from the property sector to more sophisticated manufacturing. The lowest rates in the world are already attained in China. Higher overall supply and lower prices have been attributed to technology and advanced manufacturing, which has caused a downward trend in supply curve shifts.

China’s automobile industry is the poster boy for this growth as soaring funding and fierce opposition among new EV participants flood the marketplace with whizzbang designs with possibly higher efficiency and more creative features.  ,

In 2024, the average new car sales price in China was about RMB180, 000 ( ~US$ 25, 000 ), which bought a mid-level trimmed BYD Han large sedan. In 2020, the average new car sales price in China was RMB150, 000 ( ~$ 22, 000 ), which was good for a compact Toyota Corolla. The BYD Han was also introduced in 2020 with an entry-level price of RMB233, 000 ( ~$ 34, 000 ).

Although both ASPs and device sales have increased since 2020, the biggest gain for consumers was deflation. In 2024, Chinese customers were paying substantially higher prices for somewhat more cars. However, they were able to purchase larger, more expensive models with better performance and more advanced functions.

Chinese EVs are then expected to perform group tricks like cylinder change, map change around one vehicle, crab move ( Google it ), or jump over potholes– Knight Rider” Turbo Boost” style. In recent years, price/performance/feature wars have gotten out of hand.  ,

Glenn Luk, a Chinese analyst, has monitored the features and prices of BYD’s Qin Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle ( PHEV ) at its lowest level. Over a period of 16 years, BYD has cut Qin prices by more than half ( ~$ 14, 000 ) while quadrupling range and power.

The only instance of a true deflationary spiral to come to mind is the US Great Depression, which is incredibly uncommon. Deflation is typically self-limiting for the simple reason that prices can’t fall below zero and frequently quickly crash into underlying costs, as opposed to inflation, which has no upside cap.

Even Japan, which experienced a couple of lost decades of economic growth, did not experience a decline in living standards as deflation lowered prices, delivering higher-end goods and services as the Japanese became even more meticulous about their attention to detail and quality.  ,  ,  ,

Economic experts say that a modest level of inflation is optimal for the operation of the Keynesian economy. According to Keynes, the idea behind the concept of” the paradox of thrift” is that falling prices encourage consumers to delay purchases in order to wait for better deals.

Although this paradox may be true, modern consumers should be aware that replacement cycles are naturally deflationary and are frequently challenging for any reasonable amount of inflation to overcome, especially those with a technology component.

In 40 years, we went from shoulder-carried JVC boom-boxes to Sony Walkmans to Discmans to Apple iPods to smartphones with wireless earbuds. With “hedonic” adjustments to inflation data, whose accuracy is at best open for debate, economists attempt to make these improvements work.

Consumer goods in China are experiencing a revolution in “hedonic” improvements, not just in the auto sector. It is absurd to give hedonic improvements just a few percentage points for improvements in products and services from cars to electronics to smartphones to appliances to restaurant services to boutique hotels. Han Feizi has written on this before ( here, here and here ).

We can safely assume that growth in the medium term will be fueled more by shifting the supply curve than the demand curve, increasing aggregate supply while watching prices decline, given the apparent ascendancy of the Industrial Party faction within the Communist Party of China.

More expensive goods of higher quality are the definition of deflation in good condition. Deflation is also present in its bad form in many products of declining quality at lower prices.

Although it would be nice to see demand curve shifts, China’s leadership seems unwilling to use policy tools to accomplish that. In order to push out the demand curve, the Western economic Covid playbook recommended that consumers be given checks, which would run the risk of inflation and the loss of purchasing power.

While China has implemented targeted consumption stimulus like trade-in subsidies for EVs and discount vouchers on appliances and mobile phones, stimulus measures have largely been directed towards the supply side – fixing local government balance sheets, installing digital/smart city infrastructure and directed lending to advanced manufacturing ( e. g. EVs, solar, batteries, semiconductors, automation, etc ). China’s strategy runs the risk of deflation and unprofitable investment leading to stagnant growth.

Some analysts contend that the weak demand is to blame for China’s deflation. For the most part, this analysis stems from confusion.

Economists have never really seen supply-driven deflation in their lifetimes. Deflationary moments in recent memory have all been demand shock events – post-bubble Japan, the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, the 2008 global financial crisis, etc. China’s moribund property market provides a superficial veneer of similarity.

The glorious post-Civil War economy of the US from 1873 to 1899 was the last to experience prolonged supply-driven deflation. After bloodily settling America’s family business in favor of the North, industrialization was pursued with a vengeance. Investments in railways, steel production and manufacturing resulted in extraordinary increases in output and, subsequently, falling prices.

The likelihood of China experiencing two decades of supply-driven deflation should not be dismissed given the largely successful Made in China 2025 project, the ascendancy of the Industrial Party, and a projected tripling of China’s STEM workforce in the next two decades.

In fact, that kind of productivity increase – 20 years of deflation – may be the only way to industrialize the Global South, which needs capital and capital goods ( i. e., solar, electrical systems, infrastructure, vehicles, etc ) far more than it needs market access ( see here ).

So” What’s so bad about deflation”? we ask again. The level of economic ignorance it engenders appears to be the worst aspect of deflation.