Two electrifying moves in recent weeks have the potential to ignite electric vehicle demand in the United States. First, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, expanding federal tax rebates for EV purchases. Then California approved rules to ban the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035.

The Inflation Reduction Act extends the Obama-era EV tax credit of up to US$7,500. But it includes some high hurdles. Its country-of-origin rules require that EVs – and an increasing percentage of their components and critical minerals – be sourced from the US or countries that have free-trade agreements with the US.

The law expressly forbids tax credits for vehicles with any components or critical minerals sourced from a “foreign entity of concern,” such as China or Russia.

That’s not so simple when China controls 60% of the world’s lithium mining, 77% of battery cell capacity and 60% of battery component manufacturing. Many American EV makers, including Tesla, rely heavily on battery materials from China.

The US needs a national strategy to build an EV ecosystem if it hopes to catch up. As experts in supply chain management, we have some ideas.

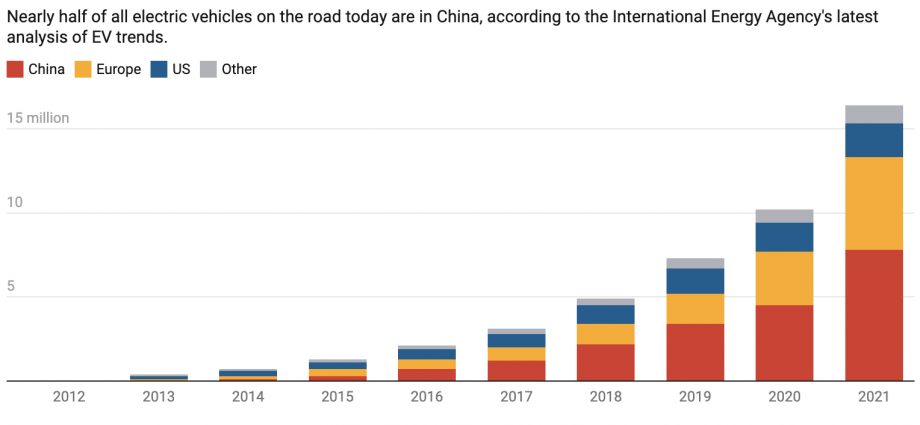

EV industry depends heavily on China

How did the US fall so far behind?

Back in 2009, the Obama administration pledged $2.4 billion to support the country’s fledgling EV industry. But demand grew slowly, and battery manufacturers such as A123 Systems and Ener1 failed to scale up their production. Both succumbed to financial pressure and were acquired by Chinese and Russian investors.

China took the lead in the EV market through an aggressive mix of carrots and sticks. Its consumer subsidies raised demand at home, and Beijing and other major cities set licensing quotas mandating a minimum share of EV sales.

China also established a world-dominating battery supply chain by securing overseas mineral supplies and heavily subsidizing its battery manufacturers.

Today, the US domestic EV supply chain is far from adequate to meet its goals. The new US tax credits are designed to help turn that around, but building a resilient EV supply chain will inevitably entail competing with China for limited resources.

A comprehensive national strategy entails measures for the short, medium and long term.

Short-term: What can be done now?

Six of the 10 best-selling EV models in 2022 are already assembled in the US, fulfilling the Inflation Reduction Act’s final assembly location clause. The Hyundai-Kia alliance, which has three of the other four bestsellers, plans to open an EV assembly line in Georgia. Volkswagen has also started assembling its ID.4 electric SUV in Tennessee.

The challenge is batteries. Besides the Tesla-Panasonic factories in Nevada and planned in Kansas, US-based battery manufacturers trail their Chinese counterparts in both size and growth.

For the US to scale up its own production, it needs to rely on strategic partners overseas. The Inflation Reduction Act allows imports of critical minerals from countries with free trade agreements to still qualify for incentives, but not imports of battery components.

This means overseas suppliers like Korea’s “Big Three” – LG Chem, SK Innovation and Samsung SDI – which supply 26% of the world’s EV batteries, are shut out, even though the US and Korea have a free trade agreement.

The Korea Automobile Manufacturers Association has asked Congress to make an exception for Korean-made EVs and batteries.

In the spirit of “friend-shoring,” the Biden administration could think of a temporary waiver as a stopgap measure that makes it easier for Korean battery makers to move more of their supply chain to the US, such as LG’s planned battery plants in partnerships with GM and Honda.

The 2021 Infrastructure Act also provided $5 billion to expand charging infrastructure, which surveys show is critical to bolstering demand.

Medium-term: Diversifying lithium and cobalt supplies

A strong and concerted effort in trade and diplomacy is necessary for the U.S. to secure critical mineral supplies.

As EV sales rise, the world is expected to face a lithium shortage by 2025. In addition to lithium, cobalt is needed for high-performance battery chemistries.

The problem? The Democratic Republic of the Congo is where 70% of the world’s cobalt is mined, and Chinese companies control 80% of that. The distant second-largest producer is Russia.

The Biden administration’s “friend-shoring” vision has a chance only if it can diversify the lithium and cobalt supply chains.

The “Lithium Triangle” of South America is one region to invest in. Also, Australia, a key US ally, leads the world in lithium production and possesses rich cobalt deposits. Waste from many of Australia’s copper mines also contains cobalt, lowering the cost.

GM has reached an agreement with the Australian mining giant Glencore to mine and process cobalt in Western Australia for its Ohio battery plant with LG Chem, bypassing China.

A way to avoid cobalt altogether also exists: lithium-iron-phosphate batteries are about 30% cheaper to make because they use minerals that are easy to find and plentiful. However, LFP batteries are heavier and have less power and range per unit.

For years, Chinese companies like CATL and BYD were the only ones making LFP batteries. But the patent rights associated with LFP batteries expire this year, opening up an important opportunity for the US.

Since not everyone needs a high-end electric supercar, affordable EVs powered by LFP batteries are an option. In fact, Tesla now offers Model 3s with LFP batteries that can travel about 270 miles on a charge.

The 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law set aside $3.16 billion to support domestic battery supply chains. With the Inflation Reduction Act’s emphasis on supporting more affordable EVs – it has price caps for vehicles to qualify for incentives – these funds will be needed to help scale up domestic LFP manufacturing.

Long-term: US critical mineral production

Replacing overseas critical materials with domestic mining falls under long-term planning.

The scale of current domestic mining is minuscule, and new mining operations can take seven to 10 years to establish because of the lengthy permitting process. Lithium deposits exist in California, Maine, Nevada and North Carolina, and there are cobalt resources in Minnesota and Idaho.

Finally, to build an industrial commons for EVs, the US must continue to invest in research and development of new battery technologies.

Also, end-of-life battery recycling is essential to the sustainability of EVs. The industry has been kicking the can down the road on this, as recycling demand has been minuscule thus far given the longevity of batteries. Yet, as a proactive step, the Inflation Reduction Act specifically permits battery content recycled in North America to qualify for the critical mineral clause.

To make this happen, the federal and state governments could use takeback legislation similar to producer responsibility laws for electronic waste enacted in more than 20 states, which stipulate that producers bear the responsibility for collecting, transporting and recycling end-of-cycle electronic products.

What’s ahead

With the new law, the Biden administration has set its sights on a future transportation system that is built in the US and runs on electricity. But there are supply chain obstacles, and the US will need both incentives and regulations to make it happen.

California’s announcement will help. Under the Clean Air Act, California has a waiver that allows it to set policies more strict than federal law. Other states can choose to follow California’s policies.

Seventeen other states have adopted California’s emissions standards. At least three, New York, Washington and Massachusetts, have already announced plans to also phase out new gas-powered cars and light trucks by 2035.

Ho-Yin Mak is Associate Professor in Operations & Information Management, Georgetown University; Christopher S. Tang is Professor of Supply Chain Management, University of California, Los Angeles, and Tinglong Dai is Professor of Operations Management & Business Analytics, Carey Business School, Johns Hopkins University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.