The short-seller’s report alleged the conglomerate had artificially inflated its market value using related-party transactions conducted through tax havens.

The stock market reaction sent the firm’s billionaire founder, until then Asia’s richest man, tumbling down the ranks of global rich-listers, though shares in the group’s listed entities have since stabilised.

The firm denies the accusations and threatened to sue Hindenburg.

It has also launched legal action against other foreign critics: It is suing environmental activist Ben Pennings in Australia, claiming he cost it millions during his campaign against its coal mining project in Queensland.

Two journalists from broadcaster CNBC TV18 have been hit with criminal defamation cases by an Adani subsidiary accusing them of a “grossly malicious, defamatory and false” news report.

“Adani Group believes strongly in the freedom of the press and like all companies retains the right to defend itself against defamatory, misleading or false statements,” a conglomerate spokesperson told AFP.

“In the past, Adani has at times exercised those rights. The group has always acted in accordance with all applicable laws.”

“FINANCIAL TERRORISM”

Hindenburg’s allegations made headlines around the world, but many Indian media outlets have ignored or dismissed them, or denounced the authors.

Several echoed Adani Group’s assertion that Hindenburg’s report was a deliberate “attack on India”, with one television panellist calling it an act of “financial terrorism” against the country.

The conglomerate’s founder has a close relationship with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and opposition lawmakers say both have benefitted from their mutual association.

Critics say Indian media’s reluctance to probe the Adani allegations reflects the close ties between the two men.

“That’s got a lot to do with Adani’s story being linked to the Modi story,” said journalist Manisha Pande of Newslaundry, a website known for critical coverage of India’s media landscape.

India has nearly 400 television news channels but Modi’s government generally benefits from enthusiastically positive coverage.

Hindenburg’s report, according to Pande, was “seen as an attack on not just a corporate house, but an attack on Modi, his decision, his tenure”.

“SUBSERVIENT”

Adani became a media owner himself in December after taking over broadcaster NDTV, which was previously known as one of the few media outlets willing to explicitly criticise India’s leader.

The tycoon batted away press freedom fears and told the Financial Times that journalists should have the “courage” to say “when the government is doing the right thing every day”.

Within hours of Adani’s takeover, one of NDTV’s most popular anchors stepped down.

Ravish Kumar, a vocal critic of Modi, later said he was “convinced” the purchase was aimed at silencing dissent.

“Adani does not promote questioning or criticism in any manner,” he told online news portal The Wire.

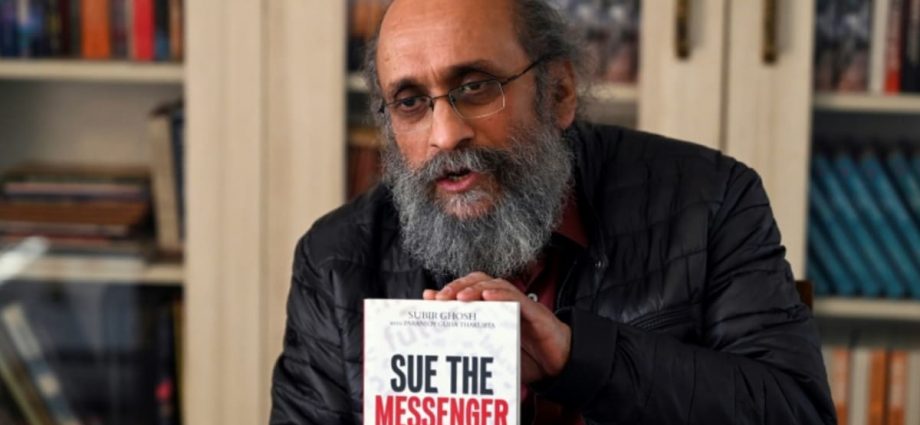

Thakurta told AFP that numerous Indian business leaders had taken stakes in media houses to “shut out opinions and information that does not favour them”.

He said Indian media acted as a “nexus” between corporate and state power.

“It should not be surprising that such a large section of media in India should be so subservient to big business interests.”