Hong Kong leader John Lee Ka-chiu proved quite the online sensation when he went on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like microblogging site, to condemn United States House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan earlier this month.

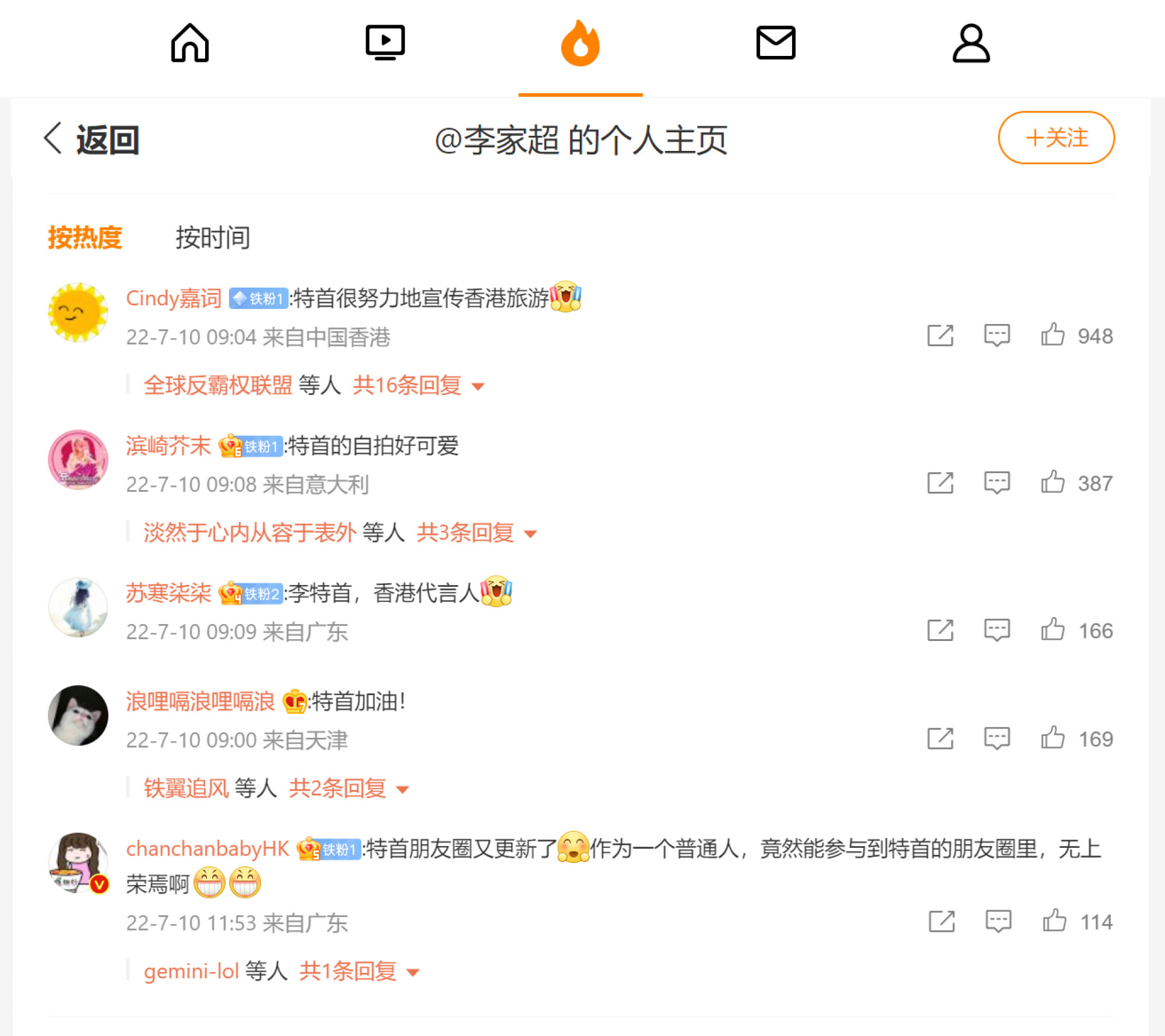

About 3,000 comments flooded his account in a day, mostly from mainland Chinese across the country, and mostly full of praise.

“The tone you now adopt is more like a mainland diplomat – a sign of a closer relationship between us!” gushed Internet user “Heiheihei Xiao” from Heilongjiang, China’s northernmost province.

The first Hong Kong leader on the mainland’s social media scene, Lee has amassed 1.46 million Weibo followers in just six weeks since taking office on July 1.

They vastly outnumber his 30,800 followers on Facebook and 7,300 on Instagram, even though he puts out almost identical content on all three platforms.

One explanation could be that Weibo has 582 million active monthly users whereas Facebook – which is banned on the mainland – has 4.45 million users in Hong Kong, according to latest official figures.

Political communications scholars said Lee’s popularity on Weibo could be the result of platform owner Sina promoting his account to mainlanders. A government insider said US sanctions barred him from paying to promote his Facebook posts.

Lee’s Weibo followers have been lapping up his posts and selfies, including the photo of his chicken rice meal one day, saying he had only 25 minutes for lunch because he had a full afternoon of appointments.

Aside from the majority heaping cheers, approval and support, some have made policy recommendations, including urging him to resume quarantine-free travel with the mainland.

When he posted a selfie posing with a giant lantern, Guangdong-based follower “ChanchanbabyHK” said: “I feel extremely privileged to be part of the chief executive’s circle of friends.”

But social media analysts noted that so far, Lee had attracted mostly one-dimensional support from the same kind of followers, and he needed to do more to draw in people with different opinions and engage them.

They said he appeared to use social media more as “government information providers” rather than a way to connect and interact with the public.

“It’s more important than ever for the government to gather constructive views extensively from society now that numerous civil society groups have either disbanded or become silent,” said Francis Lee Lap-fung, head of Chinese University’s school of journalism and communications.

He cautioned that having followers of only one type created “an atmosphere characterised by homophily”, building in effect an echo chamber which could hurt the process of deliberating and formulating policy.

Why not WeChat? Lee chose the police way

In a recent interview with state-owned media, the city leader referred to the big response to his Weibo debut and said the ardent reactions of mainlanders made him reflect on how to handle cross-border relations.

“‘Telling Hong Kong stories well’ is important in Hong Kong as well as on the mainland. We are one family. As long as our mainland compatriots understand Hong Kong more, the cross-border relationship will be improved, ” he told China News Service on Aug 2.

It was Lee’s own idea to go on social media on the mainland and he mentioned it some months ago while running as the sole candidate in the chief executive election, a close campaign aide revealed.

Instead of using Tencent’s all-purpose social media app WeChat, the aide said, the team went with Weibo because two core members in the Chief Executive’s Office were familiar with it.

Communications secretary John Tse Chun-chung, a former police chief superintendent who fronted daily press conferences during the 2019 social unrest, used to manage the force’s Weibo account, which had 489,000 followers. Special assistant Jenny Wong Tsz-yuen, a former Phoenix TV journalist, has 1.3 million followers of her own on Weibo.

Lee was also persuaded to choose the platform for his experiment in engaging mainlanders as many central government agencies had well-received Weibo accounts, the aide said.

The top performing accounts in terms of influence and interactions in June were those of China Police Online, the Communist Youth League and China Fire and Rescue Force, according to Weibo data. The Chinese police force’s account, operated by the Ministry of Public Security, had 32 million followers.

‘Did Sina boost Lee’s Weibo account?’

Of the 1.46 million followers Lee has gained in six weeks, Beijing-based users made up 10 per cent, outnumbering those from Guangzhou and other major cities, according to internal data obtained by the Post. Fewer than 3 per cent were in Hong Kong.

Former journalist Rose Luqiu Luwei, a Baptist University scholar who has researched Chinese social media, said the growth of Lee’s fan base was “exponential”, considering it often took mainland celebrities months to attract as many followers.

But she said there were two possible reasons the sheer numbers might not reflect the true level of his popularity on the mainland.

First, Sina was likely to have picked Lee’s new account to promote because of who he was, as it was still uncommon for mainland officials to operate Weibo accounts in their personal capacity.

“Some mainlanders viewed Lee’s Weibo account as a rare window to understand Hong Kong through the eyes of an official. His selfies and lunchbox display might have impressed some,” said Luqiu, who runs the university’s master’s programme in international journalism studies.

Second, she said, as Sina required all users to verify their Weibo accounts with real names since 2015, it was an open secret that mainland marketing companies bought and passed off idle accounts as followers for their clients.

But an official said Lee’s office did not spend a cent to boost his Weibo account.

Luqiu also felt that while Lee sought to create a social media image of himself as an approachable, transparent leader, his online efforts were one-directional and superficial.

“Lee does not respond to comments, retweet content or follow any accounts. We can’t say he has interacted with others in terms of social media language,” she said.

‘Many are watching, even if they don’t react’

The 30,800 followers Lee has gathered so far on Facebook still fall far behind those of other prominent Hong Kong politicians.

Pro-Beijing lawmaker Junius Ho Kwan-yiu has 254,000 followers on his public page, former leader Leung Chun-ying has 204,000, and a page that mocks Lee’s fluency and choice of words in Chinese has 60,900.

Lee started his Facebook page on June 28 this year, while Ho and Leung ran their pages and personal accounts in 2011 and 2015 respectively.

Data from Facebook’s parent company Meta showed there were 4.45 million users in Hong Kong early this year.

The government insider said Meta restrictions following sanctions imposed by the US meant Lee could not pay Facebook to run advertisements or boost his posts. His base of followers was “100% organic”, the source said.

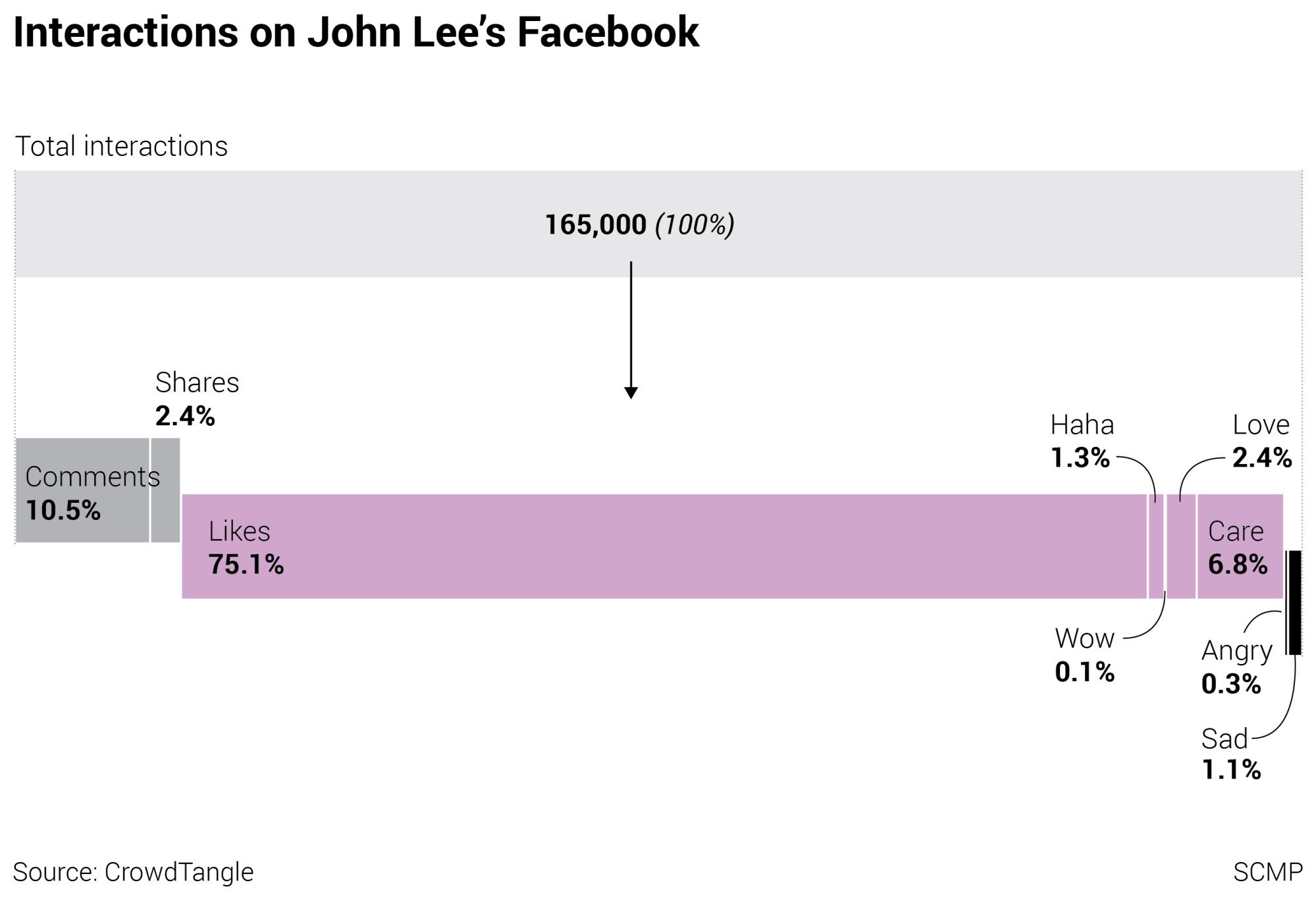

An analysis of the responses and interactions on Lee’s Facebook page so far showed it was swamped with comments from pro-Beijing politicians in Hong Kong and overwhelmed by positive emojis.

As of Tuesday, 85.7% of all 165,000 interactions were positive. “Likes” made nearly three out of four interactions, followed by “care” (6.8%) and “love” (2.4%). Only 1.4% indicated “angry” or “sad” responses.

Those who commented on Lee’s posts or shared them made up 12.9% of the total.

The sentiments on Lee’s Facebook page were in sharp contrast to the response his predecessor Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor received when she launched an official Facebook page as a chief executive election candidate in February 2017. Her posts attracted 72,000 “angry” emojis within a single day, and only 6,300 “likes”.

At the height of anti-government protests in 2019, Lam’s attempts to reach out to the public through Facebook live sessions were also greeted with a blast of negative reactions and harsh comments.

She exited Facebook and Instagram on June 30, her last day in office.

The government insider said Lee had hoped to consolidate support and improve his administration’s relationship with the city’s legislature, so some lawmakers were tagged in his Facebook posts.

It is understood that the Chief Executive’s Office explored methods used by the police force to increase exposure of their content to opposition supporters.

After the pro-democracy Occupy protests of 2014 which shut down parts of the city for 79 days, police placed advertisements on Facebook pages popular with certain demographic groups.

The ads attracted protest leaders who responded with negative comments, which then drew their tens of thousands of supporters to visit their pages and see what the force said.

“The police strategy succeeded in exposing the force’s messages to those who were hard to reach,” the insider said, adding however that the US sanctions made it impossible to place ads now.

The source did not think that the apparent one-sidedness of responses to Lee’s social media posts hurt his efforts. His messages could still reach dissidents, except that many were now reluctant to reveal their presence on social media.

“The social media ecology has changed. The dissenting voices have apparently disappeared but actually, many are keeping an eye on us. But there’s nothing we can do if people decide not to leave a comment,” the source said.

Chinese University’s Francis Lee said studies had shown that political developments in recent years had left more Hongkongers feeling indifferent, helpless about social affairs and fearful of expressing their views on social media.

He argued that the city leader’s short-term goal to consolidate supporters could end up creating a perception that he had widespread support and this could affect the process of deliberating policies.

“Those who hold different opinions might ask, will my comments just sink to the bottom or be driven out by others?” he said.

In his interview with state-owned media, city leader Lee said he had been encouraging colleagues to make better use of social media to disseminate messages and gather feedback, adding that previous government efforts went unnoticed.

Chief Secretary Eric Chan Kwok-ki, Financial Secretary Paul Chan Mo-po and security minister Chris Tang Ping-keung were among officials who set up their own Facebook public pages recently.

Baptist University’s Luqiu suggested that Lee and his administration explore other channels to expand their reach on the mainland, saying censorship had taken a heavy toll on Weibo, prompting well-educated users to switch to WeChat.

“Weibo is now clearly in decline,” she said. “But WeChat public accounts prefer users to have frequent updates and tailor-made contents. If Lee is to develop a WeChat account, more effort will have to be made.”

The government insider said the Chief Executive’s Office was exploring ways to engage, including by replying to viral comments, creating posts that summarise public responses, and designing social challenges to connect to a wider audience.

But Chinese University’s Lee said there was still an elephant in the room – how to create a social media presence that encouraged people to speak their minds and offer views, and for officials to embrace different opinions.

“Lee’s administration should look at ways to make people believe their voices could still contribute to society,” he said. “Only this can help him deliver policies, achieve results and rebuild trust.” – South China Morning Post