US income inequality grew in 2021 for the first time in a decade, according to data the Census Bureau released in September 2022.

That might sound surprising, since the most accurate measure of the poverty rate declined during the same time span.

But for development experts like me, this apparent contradiction makes perfect sense. That’s because what’s been driving income inequality in the United States – and around the world for years – is that the very rich are getting even richer, rather than the poor getting poorer.

In every major region of the world outside of Europe, extreme wealth is becoming concentrated in just a handful of people.

Gini index

Economists and other experts track the gap between the rich and the poor with what’s known as the Gini index or coefficient.

This common measure of income inequality is calculated by assessing the relative share of national income received by proportions of the population.

In a society with perfect equality – meaning everyone receives an equal share of the pie – the Gini coefficient would be 0. In the most unequal society conceivably possible, where a single person hoarded every penny of that nation’s wealth, the Gini coefficient would be 1.

The Gini index rose by 1.2% in the US in 2021 to 0.494 from 0.488 a year earlier, the Census found. In many other countries, by contrast, the Gini has been declining even as the Covid-19 pandemic – and the deep recession and weak economic recovery it triggered – worsened global income inequality.

Inequality tends to be greater in developing countries than wealthier ones. The United States is an exception. The US Gini coefficient is much higher than in similar economies, such as Denmark, which had a Gini coefficient of 0.28 in 2019, and France, where it stood at 0.32 in 2018, according to the World Bank.

Wealth inequality

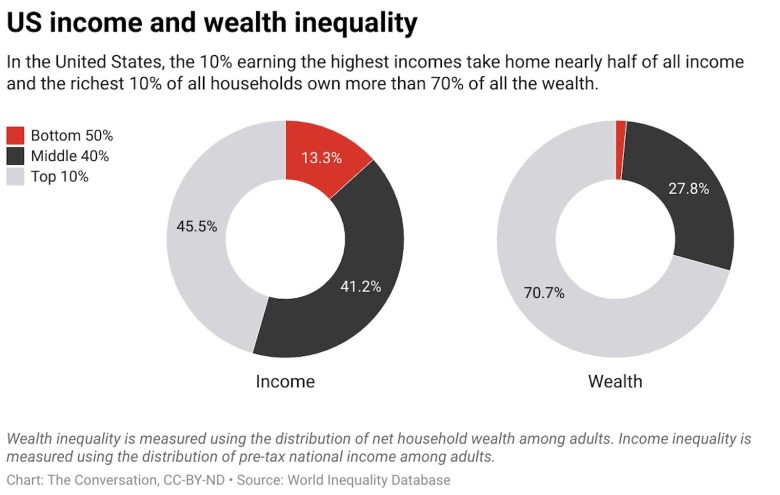

The inequality picture is even bleaker when looking beyond what people earn – their income – to what they own – their assets, investments and other wealth.

In 2021, the richest 1% of Americans owned 34.9% of the country’s wealth, while average Americans in the bottom half had only US$12,065 – less money than their counterparts in other industrial nations. By comparison, the richest 1% in the United Kingdom and Germany owned only 22.6% and 18.6% of their country’s wealth, respectively.

Globally, the richest 10% of people now possess nearly 76% of the world’s wealth. Meanwhile, the bottom 50% own just 2%, according to the 2022 World Inequality Report, which analyzes data and the work of more than 100 researchers and inequality experts.

Drivers of extreme income and wealth

Large increases in executive pay are contributing to higher levels of income inequality.

Take a typical corporate CEO. Back in 1965, he – all CEOs were white men then, and most still are today – earned about 20 times the amount of an average worker at the company he led. In 2018, the typical CEO earned 278 times as much as their typical employees.

But the world’s roughly 2,700 billionaires make most of their money not through wages but through gains in the value of their stocks and other investments.

Their assets grow in large part because of a cascade of corporate and individual tax breaks, rather than salaried wages granted by shareholders. When the wealthy in the United States earn money from capital gains, the highest tax rate they pay is 20%, whereas the highest income earners are on the hook for as much as 37% on every additional dollar they earn.

This calculation does not even count the effects of tax breaks, which often slash the real-world capital gain tax to much lower levels.

Tesla, SpaceX and Twitter CEO Elon Musk is currently the world’s richest man, with a fortune of $240 billion, according to a Bloomberg estimate.

The $383 million he made per day in 2020 made it possible for him to buy enough Tesla Model 3 cars to cover almost the whole of Manhattan had he wished to do so.

Musk’s wealth accumulation is extreme. But the founders of several tech companies, including Google, Facebook and Amazon, have all earned many billions of dollars in just a few years. The average person could never make that much money through a salary alone.

Another day, another billionaire

A new billionaire is created every 26 hours, according to Oxfam, an international aid and research group where I used to work.

Globally, inequality is so extreme that the world’s 10 richest men possess more wealth than the 3.1 billion poorest people, Oxfam has calculated.

Economists who study global inequality have found that the rich in large English-speaking countries, along with India and China, have seen a dramatic rise in their earnings since the 1980s. Inequality boomed as deregulation, economic liberalization programs and other policies created opportunities for the rich to get richer.

Why inequality matters

The rich tend to spend less of their money than the poor. As a result, the extreme concentration of wealth can slow the pace of economic growth.

Extreme inequality can also exacerbate political dysfunction and undermine faith in political and economic systems. It can also erode principles of fairness and democratic norms of sharing power and resources.

The richest people have more wealth than entire countries. Such extreme power and influence in the hands of a select few who face little accountability is raising concerns that are part of a robust debate on whether and how to address extreme inequality

Many proposed solutions call for new taxes, regulations and policies, along with philanthropic strategies like using grants and community-based investments to dismantle inequality.

Voters in some states, like Massachusetts, will get to weigh in on whether to raise taxes on the income earned by their richest residents in ballot initiatives in November 2022.

Proponents of these initiatives claim the revenue raised would boost funding for public services, such as education and infrastructure. US President Joe Biden is also proposing to almost double the top capital gains tax for those making over $1 million.

However societies choose to act, I believe change is needed.

Fatema Z Sumar is Executive Director of the Center for International Development, Harvard Kennedy School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.