LONDON and SINGAPORE – Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s three-month-old administration won a key legal victory last week when Abu Dhabi’s International Petroleum Investment Co (IPIC) and its Aabar Investments PJS unit agreed to pay US$1.8 billion to settle a legal dispute linked to the sprawling 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB, scandal.

The two sides had been locked in proceedings at the London High Court since 2018, when Malaysia challenged the validity of an arbitration award that had been negotiated between 1MDB and IPIC a year earlier during the premiership of Najib Razak, with the then-government arguing that the 2017 settlement was procured by fraud.

Anwar recently called the settlement a “huge success” for Malaysia and heaped praise on the country’s civil servants for their negotiating prowess, remarking that the amount reclaimed had exceeded his expectations. The premier now hopes to claw back even more money in a separate 1MDB-related dispute with Wall Street investment bank Goldman Sachs.

In January, Anwar called on Goldman to honor a settlement agreement reached in July 2020 under which the US bank, which helped to raise $6.5 billion from three bonds for 1MDB in 2012 and 2013 that would later be misappropriated, agreed to pay $2.5 billion while guaranteeing the return of $1.4 billion of 1MDB assets seized by authorities around the world.

Under the agreement, Goldman is obliged to make a one-time interim payment of $250 million if Malaysia failed to receive at least $500 million in assets and proceeds by August 2022. The two sides are now at loggerheads over that commitment, with Goldman claiming that it has identified assets to the value of $500 million while the country argues there is an $80 million shortfall.

Goldman, in a filing to the United States’ Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) dated October 2022, accused the Malaysian government of “unilaterally reducing” the value of an asset included in its prior reports by $80 million. The filing said Putrajaya had also “declined to include substantial additional assets in its accounting of assets and proceeds recovered.”

“Goldman tallied up the total amount recovered through all channels of assets, related to 1MDB. They have re-valued one of the assets and they are saying that others don’t qualify as counting to the $500 million. Goldman thinks Malaysia has received $500 million and they’re saying no we haven’t,” said a source close to Goldman Sachs who requested anonymity.

“They have acknowledged some assets were eligible for the total and then they have changed their minds. They have unilaterally decided this doesn’t count to the total,” said the same bank source, who claimed that Malaysia, which has been led by four governments in as many years, has been insufficiently rigorous in pursuing 1MDB-related assets.

“The global asset recovery process is complicated. The country has to knock on the doors of foreign governments […] to make a case that these assets were derived from money stolen from 1MDB. You have to take steps to make that happen. It doesn’t happen passively. How proactive is Malaysia being in the process?”

The interpretation of the agreement, negotiated during the tenure of former premier Muhyiddin Yassin, is now being hotly contested. Anwar, in an interview with Bloomberg, called on the bank to “pay what’s due, be reasonable with us and negotiate the terms,” while suggesting the country would be prepared to review the agreement if matters “are not settled amicably.”

“My only appeal is for them to settle this deal with Malaysia because 1MDB is known throughout the world. It is there in the books and I think that Goldman Sachs should come out clean and deal with Malaysia,” said Anwar, who added that the country should have been paid “much more” than the amount stated in the settlement if given a fair deal.

The premier, who has emphasized fiscal prudence to rein in the country’s 1.5 trillion ringgit ($344 billion) national debt and liabilities, said in the same interview that the global recovery of assets linked to 1MDB is “still in process” and called on the Wall Street firm not to dismiss its “moral and financial responsibilities” in settling the matter with Malaysia.

Questions have since been raised about the terms of the agreement, under which Malaysia agreed to drop criminal charges against Goldman and 17 of its executives. The settlement, reached by Muhyiddin’s government after less than five months in office, has been widely criticized for settling well below the $7.5 billion in compensation demanded by the previous administration.

The rationale behind the bank’s asset guarantee to Malaysia has also come into question, with some local politicians asking why the government did not instead insist on a larger payout. Critics have called on the Anwar administration to publish the terms of the settlement, which has thus far been withheld due to an alleged confidentiality provision prohibiting its release.

“The government of Malaysia agreed to a bad deal with Goldman. They should have demanded cash in the bank, not assets,” said a former law officer who requested anonymity. “They have lost the initiative. There must be a question about the way the government made the agreement. This is a dispute which can only be resolved by the publication of the agreement.”

Pushpan Murugiah, chief executive of the Kuala Lumpur-based Center to Combat Corruption and Cronyism (C4), an anti-corruption group, has suggested that Malaysian officials involved in the negotiations with Goldman should be probed by a Public Accounts Committee (PAC) to address concerns of the settlement being made without proper oversight.

Due to the settlement’s non-disclosure clause, the nature of the assets in dispute is unclear. While addressing the matter in parliament, however, former deputy finance minister Johari Abdul Ghani implied that Goldman had tallied 1MDB-related fines levied against Malaysian banking group AMMB Holdings Berhad (Ambank) and settlements from audit firms KPMG and Deloitte PLT.

“They want to take these penalties levied against entities in Malaysia, and deduct it from the $1.4 billion in assets,” Johari claimed. Ambank had agreed to pay the Malaysian government the equivalent of $700 million to settle claims linked to 1MDB in 2021. KPMG and Deloitte each paid fines of $80 million to resolve all claims related to its auditing of 1MDB-linked accounts.

P Gunasegaram, a columnist, independent analyst and author of the book “1MDB: The Scandal that Brought Down a Government”, told Asia Times that if the bank’s guarantee, the specifics of which remain confidential, covers only “recoveries from assets purchased with the proceeds of the bond issues”, then Goldman cannot credibly include fines levied against other financial institutions.

Goldman Sachs did not respond to Asia Times’ request for comment. In its October filing, the bank, which has been probed by regulators in at least 14 countries for its role in underwriting the 1MDB bond issues, noted that the parties had a three-month window to resolve the dispute and that the matter would be settled by arbitration if no resolution is reached.

Gunasegaram believes the government will reach a deal with Goldman before arbitration “as neither would want details to be public.” But he added that Anwar should make all details public in the interest of transparency and accountability. “If there’s the slightest indication of foul play, he should order a full investigation. Inaction will cause a loss of credibility in the new government.”

A regulatory filing from late February showed that Goldman is expecting to incur $2.3 billion more in potential losses from legal proceedings than the reserves it had set aside for such disputes a year earlier. Apart from 1MDB, the bank has been the target of lawsuits linked to alleged insider trading in relation to the collapse of investment fund Archegos Capital Management in 2021.

Goldman agreed to a separate $2.9 billion settlement and deferred prosecution agreement with the US Department of Justice (DoJ) in October 2020 over its role with 1MDB. The bank also agreed for its Malaysian subsidiary to plead guilty in a US federal court, though it had claimed to be misled by former premier Najib’s government about how the 1MDB bond proceeds would be used.

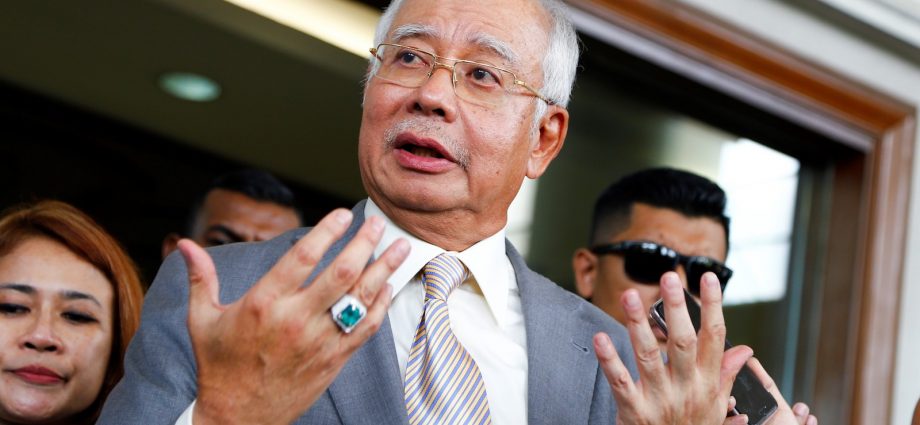

Najib was found guilty of 1MDB-related corruption charges by Malaysia’s highest court and began serving a 12-year prison sentence in August last year. The former premier won a rare legal battle on March 3 when a court acquitted him of allegedly tampering with 1MDB’s audit papers in 2016.

Najib remains on trial in four other graft cases and has applied for a royal pardon from Malaysia’s king.

Nick Kochan reported from London; Nile Bowie reported from Singapore.