The fear of artificial intelligence is largely a Western phenomenon. It is virtually absent in Asia. In contrast, East Asia sees AI as an invaluable tool to relieve humans of tedious, repetitive tasks and to deal with the problems of aging societies. AI brings productivity gains comparable to the ICT (information and communications technology) revolution of the late 20th century.

China is using AI as an integral part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which brings together different “Industry 4.0” technologies – high-speed (fifth-generation) communications, the Internet of Things (IoT), robotics, etc. Chinese ports unload container ships in 45 minutes, a task that can take up to a week in other countries.

Today’s fear of AI has many parallels to the fear of machines at the end of the 19th century. French textile workers, fearing mechanical weaving would endanger their jobs and devalue their craft, threw their “sabots” (clogs) into weaving machines to render them inoperable. They gave us the word sabotage.

In the 20th century, machines and a multitude of power tools relieved humans of most physical labor. In the 21st century, AI will relieve humans of most mental labor.

But AI’s challenge to the human mental faculty has created a growing community of AI alarmists. Much of this can be traced to science (cyber) fiction, which often features out-of-control AI systems.

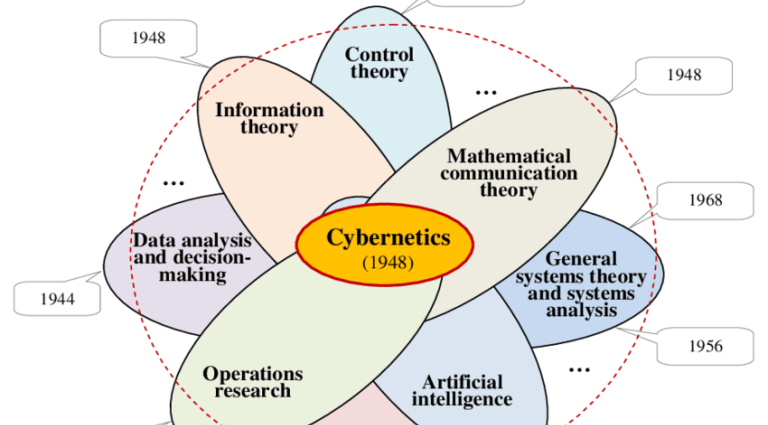

Paranoia is part of AI history. The new science emerged in the 1960s on the back of cybernetics, the first coherent computer science for digital (binary) computers. The autopilot used in airliners is a textbook example of a cybernetic system.

AI is cybernetics with a self-learning function. Rather than naming it Cybernetics 2.0, its developers used the intriguing name “artificial intelligence,” assuming it would make it easier to attract funding. And they were right.

The AI pioneers predicted that a machine as intelligent as a human being would exist in no more than a generation, and they were given millions of dollars to make it happen. They didn’t bother to define the word “intelligence,” and after a few years, the project was shelved. That led to the so-called “AI winter.”

Emergence from hybernation

In the 1990s, IBM’s “Big Blue” put AI back on the front pages when it beat world chess champion Gary Kasparov. The landmark achievement was possible thanks to dramatic advances in computing power. While impressive, a computer beating a human at chess was a matter of number-crunching. Big Blue could simply calculate more winning moves faster than Kasparov could.

Thirty years later, ChatGPT has once again rekindled interest in AI, as well as the old paranoia. In March this year, a group of AI experts called on all AI labs “to immediately pause for at least six months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4” (the current iteration of ChatGPT).

The open letter, signed by such luminaries as Elon Musk, piled on the paranoia. They ask: “Should we develop non-human minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete, and replace us? Should we risk the loss of control of our civilization?”

Other AI experts go even further, calling AI a bigger danger to humanity than climate change. Some voice the fear that humanity is at risk of being enslaved by AI. But none of these experts provide concrete examples of how such doomsday scenarios would occur.

All AI systems, whether Big Blue, a self-driving car, or ChatGPT, are domain-specific. An AI system designed for an autonomous vehicle can’t play chess. They are designed to perform a specific task within the parameters set by the designers.

AI systems consist of an algorithm that has access to an internal or external database. They operate on Boolean logic to process the information they can access (true/false/if/then/or, etc). They don’t make up facts and don’t have a will of their own.

Chat systems are impressive and will impact or even eliminate many jobs and will render entire professions obsolete, but they are only one part of a much broader technological (Industry 4.0) ecosystem. The technology is already transforming nearly all areas of the Chinese economy.

Health care: AI is used in China’s health-care industry for medical imaging analysis, disease diagnosis, and drug research. AI algorithms analyze medical images and help doctors detect abnormalities or assist in diagnosing diseases.

Smart cities: Chinese cities are deploying AI technologies to create smart urban environments, including traffic management, energy efficiency, waste management, and public safety systems that utilize AI to optimize operations and enhance citizen services.

Education: AI is integrated into China’s education system to improve personalized learning experiences. Intelligent tutoring systems and adaptive learning platforms use AI algorithms to tailor educational content and provide personalized feedback to students.

Agriculture: AI has been deployed in agriculture for crop monitoring, pest detection, and yield optimization. Drones equipped with AI algorithms survey farmland, analyze crop health, and identify areas requiring attention.

Cultural factors, including pragmatism, explain why China has a higher level of acceptance and trust in technology than the West. The Chinese see AI as just one part of a larger development in the transition to the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Accidents and mistakes can happen in the development of technology, and AI needs guardrails, just like the atomic energy industry and civil aviation do. If an algorithm is allowed or enabled to get out of control, the programmer is at fault. Common sense dictates that any system able to impact the lives of millions is tested behind a firewall.

It is commonly said that in AI, the US leads in innovation and China leads in application. That may be true, but the US should be concerned that it does not innovate itself into oblivion by neglecting its infrastructure.

To be fully transformative, AI needs to operate in an Industry 4.0 ecosystem. That’s where China had a head start, and would be a better focus of concern in the American AI community.