Fang Bin, who documented the initial Covid outbreak in the Chinese city of Wuhan, has been freed from jail after three years, sources told the BBC.

Mr Fang is one of several so-called citizen journalists who disappeared after sharing videos of scenes in Wuhan, the epicentre of the pandemic.

After disappearing in February 2020, he was sentenced to three years in jail at a secret trial in Wuhan, sources said.

He was released on Sunday and is in good health, they added.

Mr Fang is now back home in Wuhan. The BBC could not reach his family for comment.

Although activists have welcomed his release, they are concerned about the fate of another whistleblower – Zhang Zhan, a 39-year-old former lawyer, was detained in May 2020 and jailed for four years in December 2020.

Like Mr Fang, she too was convicted for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”, according to activists who say the vague offence has often been used against critics of China’s government. Two other citizen reporters Chen Qiushi and Li Zehua also disappeared in Wuhan in February 2020, but surfaced months later.

Their videos provided a rare glimpse into Wuhan in the early months of 2020. Cases were climbing and lockdowns had come into force, but information from officials remained scarce. Wuhan’s 76-day lockdown – which inspired the country’s harsh zero-Covid strategy – put the city under severe strain.

The video by Mr Fang that caught the attention of the outside world was one where he counted eight body bags outside a Covid hospital in the space of five minutes. He said he was detained that night but released. Then came a video with the message: “All people revolt – hand the power of the government back to the people”. That was the last video he shared.

Ms Zhang, who lived in Shanghai, travelled to Wuhan in February 2020 to report on the outbreak after reading about a resident’s experience. She was active on YouTube and Twitter, both of which are banned in mainland China, and continued sharing videos despite reportedly being threatened by local authorities.

“Maybe I have a rebellious soul… I’m just documenting the truth. Why can’t I show the truth?” she said in an interview with an independent filmmaker that was obtained by the BBC.

Shortly after the arrest, she began a hunger strike and was sometimes force-fed as her weight plummeted to under 40kg (88lb), according to the Free Zhang Zhan group. It’s unclear if she is still on a hunger strike. Her family knows little about her condition.

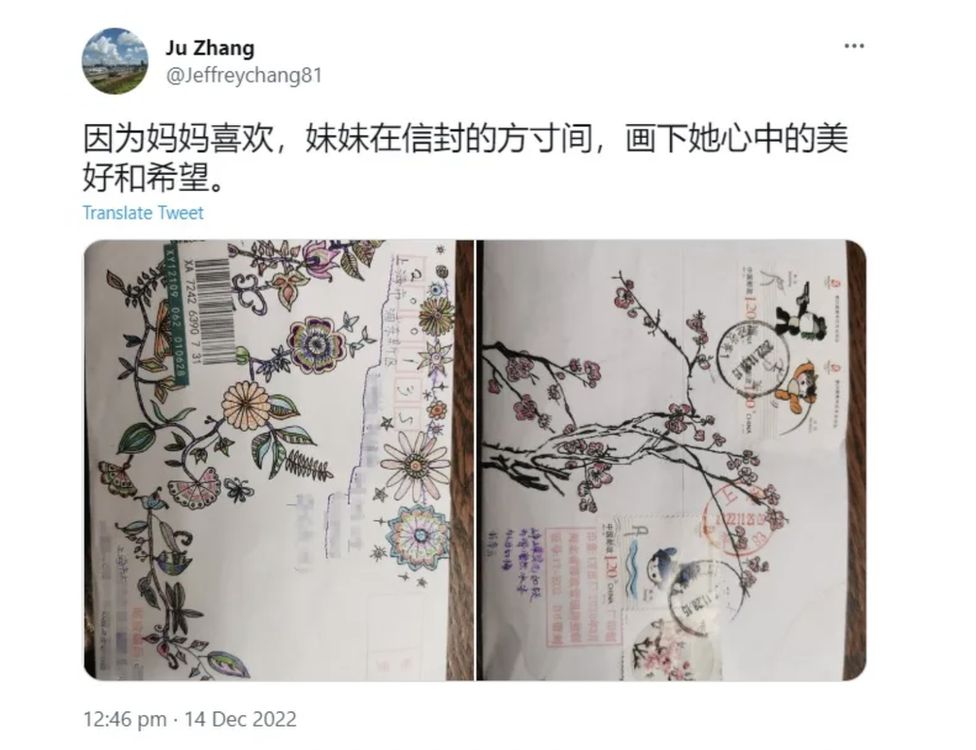

Last December, her brother uploaded photos of a letter written by Ms Zhang in now-deleted tweets. She drew flowers on the envelope to reassure their mother, he said.

In the letter, Ms Zhang mostly asked after her mother, who had recently undergone surgery and chemotherapy. She added that her mother was being treated well by the authorities.

Mr Fang’s release came quietly and with no warning as China tries to move on from the pandemic. Years of gruelling lockdowns and unyielding Covid rules took a huge toll, but their abrupt end late in 2022 brought on a devastating Covid wave.

The country has reported 120,000 deaths since the start of the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Nearly half of those were recorded between 8 December 2022 and 12 January 2023. But the numbers don’t represent the true toll.

In February, the Chinese Communist Party’s top leaders declared a “decisive victory” over Covid, boasting the lowest fatality rate in the world. They also said the country’s Covid exit was a “miracle”.

A new history textbook talks of how the government “achieved major achievements in co-ordinating the prevention and control of the pandemic”.

And China’s swift and effective censorship machine also means that the videos and accounts shared by those such as Mr Fang or Ms Zhang will likely fade from memory, if they haven’t already.

“I visited China in March, and my observation is that people there want to move on and leave the past behind,” says Yanzhong Huang, senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“They had to endure the draconian zero-Covid for a prolonged period, and now they yearn for a return to a more normal way of life.” But, he adds, that this desire to move on is also driven by the lack of public discussion or debate.

Not everyone in Wuhan has forgotten what life was like in early 2020.

One 31-year-old resident, who did not wish to reveal his full name, said he had not heard of Fang Bin but does remembers Li Wenliang, a doctor who tried to warn the world about the coronavirus and died after contracting it.

He says he often talks about the pandemic with his friends, even though he admits they might be a minority.

“Society is revising the memory of this period,” he says. He said he lived with his parents throughout the lockdown. His mother would be so anxious and wash her hands so often that her hands cracked because of it.

“My mum still doesn’t really understand the virus. If the media start reporting about virus again, she will wear a mask. She is really frightened.”

And there are others like Yang Min, who lost her only child to Covid in January 2020. She believes an early warning from officials would have saved her daughter.

Now, three years on, she is still fighting to hold officials accountable and trying to file a lawsuit against the local government.

She is under surveillance but, she told the BBC earlier this year, she was not afraid.

“I have already lost the most precious thing in life. What else can they take away from me?”

Additional reporting by Lok Lee, BBC Chinese