Countries in the Middle East view China’s growing power and influence in starkly different terms from the US and many of its Western allies. These alternative strategic perceptions are likely to have a decisive impact on geopolitics in the years to come. In some ways, they already are.

US policymakers on both sides of the political spectrum have made it clear that they view China’s growing power and influence as the No 1 threat to America’s global primacy and the liberal international order at large.

After Washington identified China as “the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to advance that objective,” many of its Western allies have slowly embraced aspects of Washington’s sentiments.

In fact, during an October 12 lecture at the Royal United Service Institute, the UK’s spy chief, Jeremy Fleming, declared: “Beijing’s efforts to exert control over technology both internationally and within China’s borders threaten future global security and freedom.”

Fleming, director of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), argued that a digital yuan might one day help Beijing evade sanctions and that China could leverage the BeiDou satellite system to block adversaries’ access to space and enhance its surveillance apparatus.

Fleming emphasized that China has proposed new international rules for the Internet that could threaten digital freedom and enhance state control, threatening human rights “by the introduction of new tracking methods,” the speech excerpts said.

To secure its digital ecosystem, the UK government banned installing new Huawei equipment in fifth-generation telecom networks. It now requires that Huawei be removed from the country’s 5G networks by the end of 2027. More recently, the UK has taken to blocking Chinese investment in its semiconductor industry.

Meanwhile, Australia issued a ban on Huawei equipment in 2018. Just a year before, Canberra scuppered a Huawei Marine deal to construct a submarine cable from the Australian continent to the Solomon Islands, citing concerns that China might access sensitive information traveling over the cables.

Australia put its money where its mouth was and offered to fund an alternative – the Coral Sea Cable – to the tune of A$200 million (US$134 million).

European governments don’t all necessarily agree with US policy prescriptions for dealing with an increasingly assertive China. However, they certainly seem to agree with Washington’s diagnosis.

During an October 2022 European Council meeting, Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo told the press that European countries were “a bit too complacent” and that in certain domains, China is “a fierce competitor,” while in others, “they have hostile behavior.”

Meanwhile, his Finnish counterpart Sanna Marin argued that Europe “shouldn’t be building that kind of strategic, critical dependencies on authoritarian countries” and called on the European Union to work with other democracies to counter China’s rise in the tech field.

Despite wishing to remain beacons of free trade, many European governments have followed Washington’s lead and are now screening against what some describe as an aggressive acquisition campaign by Chinese entities to control the world’s most advanced technologies.

The Netherlands and Japan, both makers of sophisticated equipment used in the manufacturing of microchips, have reluctantly decided to support US containment efforts, barring some shipments of their most advanced machinery to China.

Europeans have since embraced “Open Strategic Autonomy” in emerging and foundational technologies as a critical policy priority. On March 15, the Financial Times reported that the EU planned to introduce new restrictions on green technology imports from China, reducing the prospects of Chinese companies winning public tenders and creating additional barriers for buyers seeking subsidies.

It’s not just politicians and policymakers who have grown increasingly wary of China. Public opinion polls reveal that perceptions of China among Western citizenry have gradually aligned with the concerns of their respective governments.

According to Pew’s 2022 poll, 86% of Australians, 74% of Canadians, 83% of Swedes, 75% of Dutch, 74% of Germans, 69% of Britons, 68% of French, 63% of Belgians, and 64% of Italians surveyed harbor unfavorable views of China.

Alternative perceptions in Middle East

While sentiments toward the People’s Republic deteriorated across the Western world, China has experienced rising favorability across most of the Middle East.

What’s more, much of the Arab world today views China in slightly more favorable terms than the US.

The seventh iteration of Princeton University’s Arab Barometer, based on interviews with more than 26,000 citizens in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) between October 2021 and July 2022, found this to be true among people surveyed in Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, Jordan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Authority, Iraq and Sudan tend to favor China more than the US.

Morocco was the only country surveyed to have slightly more favorable views of the US (69%) than China (64%).

When it comes to anchors of US policy in the MENA, such as the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, reliable data are hard to come by. But a series of recent studies spearheaded by the Washington Institute has shed some light on the matter. According to a 2021 survey, 57% of Egyptians believed good relations with China were “important” to their country, while 55% said the same about the US.

Of 1,000 Saudi citizens surveyed by the same institute in November of the following year, 57% indicated good relations with China were “important” to Saudi Arabia, while 41% said the same about the US. That same year, the institute polled 1,000 Emiratis, 52% of whom indicated China was important for their country, while 44% shared such sentiments toward the US.

The exception in the region has been Israel, a close US ally and the only democracy in the Middle East. In 2019, 66% of Israelis surveyed viewed China favorably, while 25% had unfavorable views, according to Pew. By 2022, the proportion had shifted, with 48% viewing China favorably and 46% with opposing views.

Despite harboring slightly more favorable views of China than most of the Western world, Israel has taken steps that reflect a growing sensitivity to US and other Western countries’ concerns: implementing a foreign-investment screening mechanism, reducing the threshold for intervening in business deals, and canceling several major infrastructure projects.

However, even America’s closest regional ally is reluctant to join wholeheartedly the US crusade to contain China’s rise. Like most governments in the Middle East, Jerusalem still wishes to expand cooperation with China to the highest possible extent.

Why the gap?

It’s not that Middle Eastern countries view China as some benign power, but in fact they see China from a very different vantage point than the US or even Europe.

Jonathan Fulton and Jonathan Pannikoff, senior fellows at the Atlantic Council, note in the National Interest: “There’s a long history of extra-regional powers in the Middle East and most know an opportunistic outsider when they see one.” However, few, if any, view China as a threat – especially not in the way America does.

Quite to the contrary, some leaders in the Middle East look at China and see both immense opportunity and a model to emulate. After all, communist China transformed itself from an economic backwater to a manufacturing and technological powerhouse in just forty-odd years.

As China grew richer and more innovative, the country had more to offer and gradually became the largest trading partner and source of investment, infrastructure and technology development for most countries in the region. And China doesn’t condition this cooperation on democratizing politics or liberalizing economies.

Middle Eastern countries seeking to transform their economies from fossil-fuel dependency to innovation nations have embraced Chinese initiatives like the Digital Silk Road, which promises to upgrade their digital ecosystems and help them move up the technological value chain.

Governments in the region appreciate that failure to realize these economic reforms only invites potential economic stress that could threaten their long-term national security.

These realities help to explain why governments and enterprises from Muscat to Marrakesh continue to enlist Chinese entities to construct everything from 5G telecommunication networks to smart cities and surveillance tech despite US warnings that doing so could threaten their security ties with Washington.

In the UAE, Washington even threatened to cancel a $23 billion arms deal, including up to 50 F-35 fighter jets and 18 MQ-9 Reaper drones, if the country failed to remove Huawei from its 5G networks. However, it was the Emiratis who ultimately decided to suspend the arms deal with the US in December 2021.

But fears surrounding economic security are certainly not the only reason for the seeming lack of empathy for US concerns. Perhaps if the US accompanied its lectures with viable alternatives, it would have achieved more desirable results. But there is another reason that Middle Easterners are reluctant to throw themselves at the mercy of the US security umbrella and curb their ties with Beijing.

Deteriorating trust

Over the years, the US engaged with the region in ways that diminished trust among its local partners, from failing to respond when Syrian President Bashar al-Assad allegedly crossed US president Barack Obama’s red line in 2013 and unleashed chemical weapons to the chaotic US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Notably, Obama’s decision to sign the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Tehran in 2015 was viewed by many of Washington’s regional partners as a sure way for Iran to create a nuclear military capability while at the same time strengthening Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’s ability to continue destabilizing the region.

The US at once promises to “make [the Saudis] pay the price and make them in fact the pariah that they are” and then demands that Saudi Arabia pump more oil to lower the price of gasoline.

As one Saudi analyst explained in Foreign Policy, “most educated Saudis … feel bullied by what we see as unfair attacks by US media and policymakers against us, our country, our leaders, and our culture.”

These sentiments are largely the result of the US placing human rights before realpolitik. According to the author: “The alternative, for many [Saudis], is to learn Mandarin and imagine future careers promoting Chinese industry and trade.”

Indeed, the aforementioned Washington Institute survey confirmed that 60% of Emiratis – approximately in line with their Saudi neighbors – indicated they agree with the statement “We cannot count on the United States these days, so we should look more to Russia or China as partners.”

Despite these popular opinions among the Arab public, Middle Eastern governments don’t exactly want China to replace the US in the region. Most have rejected binary framing and have no intention of picking a side.

Anwar Gargash, diplomatic adviser to UAE President Mohammad bin Zayed Al Nahyan, has made this clear: “The UAE has no interest in choosing sides between great powers, our primary strategic relationship remains unequivocally with the United States.”

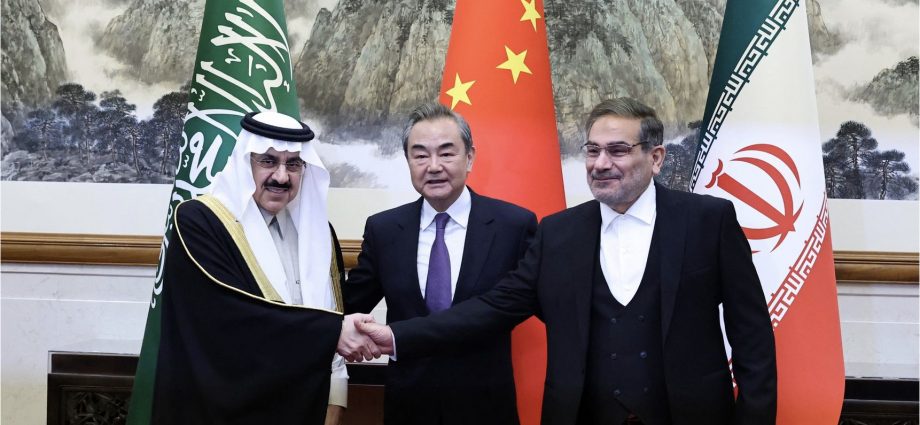

China may have succeeded in mediating some kind of rapprochement between the Saudis and Iranians, but Beijing is neither willing nor able to provide the kinds of security guarantees the US offers the region. Nevertheless, in an increasingly uncertain geopolitical matrix, few wish to put all their falafels in one pita.

Michael Singh, managing director of the Washington Institute, has called this approach “omni-alignment.” By adopting this strategy, Singh argues that these countries “are making themselves the object of competition between the great powers, while protecting their interests if one or the other draws back.”

US President Joe Biden’s declaration that “this is a battle between the utility of democracies in the 21st century and autocracies” may resonate strongly in the West. But in the Middle East, where democracies are in short supply, such rhetoric only adds further impetus for countries to hedge their bets and “omni-align.”