JAKARTA – It was dusk when photojournalist Tim Page pulled into a village deep in the mountains of northern Thailand. It had been a long day shooting opium poppies, but he had a roll of new fast film and in his mind was an image of an old man smoking an opium pipe by the dim light of a lantern.

Page soon found the village opium hut. But as he stood unsteadily on one leg taking off his shoes, the floor gave way under him and he descended feet-first into the deep mud under the house. The villagers fell about laughing, but he still got the shot. He usually did.

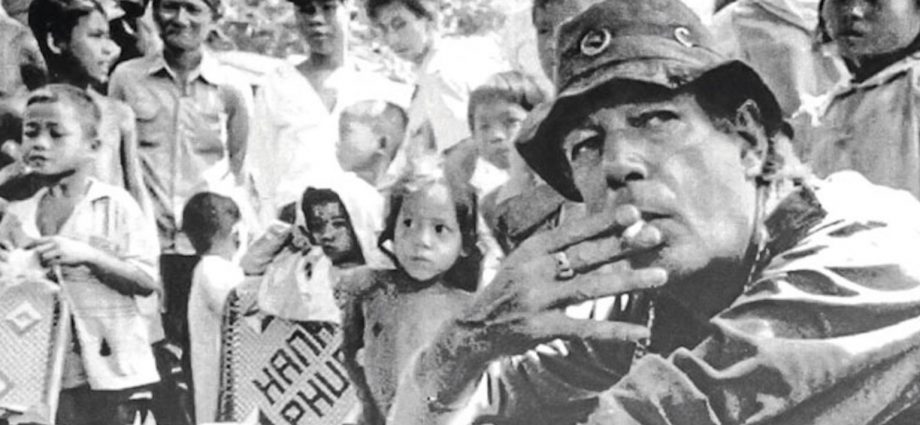

When the legendary 78-year-old cameraman died at his home in rural Australia today (August 24), his losing battle with pancreatic cancer came 53 years after he was given 20 minutes to live on a battlefield in Vietnam, the decade-long war that was to consume and define his colorful life.

At the time of his death, he was still working on digitizing his work, which began when the self-described “green hippy kid” from Tunbridge Wells, Kent, was given a camera in strife-torn Laos and pointed in the direction of the war in Vietnam.

His collection of 750,000 images is now stored in a converted refrigerated container, painted in garish camouflage and sitting near the modest house in Bellingen on the New South Wales coast where he lived with his long-time Australian partner.

“Once you’ve been to war, it’s the biggest thing in your life,” he said in one recent interview. “You form mateships, friendships, which are tougher, harder more cemented than with your family. They become your brothers and your sisters.”

As for covering war, “You learn quickly, or you die. You don’t go out there with a backdrop in your mind ‘I will be hurt this time, I will die.’ You can’t have this in your mind otherwise you won’t function because you’ll spend all your time worrying.”

It was a much more reflective Page than five decades before when, for a small band of young Saigon-based photographers hanging out in a house that came to be known as Frankie’s Place, the war meshed seamlessly with the world of drugs and rock and roll.

A 1992 British-Australian TV series of the same name sought to capture that period. “Page hated it, probably because in the first segment it made him look like a naïve and foolish young kid, running around doing crazy stuff in a war zone,” says close friend Michael Hayes, former editor of the Phnom Penh Post.

It may not have been so far off the mark.

Asked then if he would consider writing a book that took the glamor out of war, Page famously responded: “Take the glamor out of war! I mean, how the bloody hell can you do that … war is good for you, you can’t take the glamor out of that. It’s like trying to take the glamor out of sex.”

Between the height of the French Indochina War in the 1950s and the fall of Phnom Penh and Saigon in 1975, 135 photographers from all sides were reported killed or missing in the thick of combat or alone on dangerous roads at dusk.

Page was very nearly one of them. He was wounded four times covering the fighting in South Vietnam, suffering shrapnel wounds in two incidents in 1965 working for United Press International (UPI) and then twice more after that, each time progressively worse.

In August 1966, he was aboard a Coast Guard cutter strafed by three US jets that mistakenly identified it as a Viet Cong vessel. Wounds covering most of his body, he spent two hours drifting helplessly in the South China Sea before being rescued.

During his treatment for cancer earlier this year, doctors discovered he still had 10 tiny pieces of shrapnel in his liver from that incident that prevented him from undergoing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Three years later, after a break to cover the Six Day War, Page was on a helicopter called to evacuate two wounded soldiers northwest of Saigon. As he stepped off to help, a sergeant ahead of him triggered a mine, sending a two-inch piece of shrapnel into his head.

Miraculously he survived, even staggering back to the helicopter to change lens and shoot a few more frames. He doesn’t recall a lot after that, but he underwent a 10-hour life-saving operation and spent the next year in the US undergoing neuro-surgery at Walter Reed military hospital.

It left him with what he called a “gimp” and Page-being-Page he often joked that because of a plastic plate in his skull he grew his hair with petroleum products. It also introduced him to the world of LSD, which he credits with helping him through his rehabilitation.

Critics say Page’s place in photography will not be so much for his pictures, but as a photographer who got so close to the action he rarely used a long lens. “There was too much to shoot,” he once wrote. “Too many frames to be made. No time to do it.”

His long-time friend, the great Australian cameraman Neil Davis, who survived 11 years of often close combat in Indochina only to die needlessly in a military coup attempt in Bangkok in 1985, had the same instincts working mostly with Asian soldiers.

“I would always try to go to the extreme frontline,” he said in the award-winning documentary Frontline. “You can’t get the spontaneity of action if you’re not there … you can’t see the faces (of the soldiers), the expressions on the faces.”

Typically, Page regarded Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now as the best movie ever made on Vietnam, simply because it captured the madness of it all. Little wonder he was the model for the crazed cameraman in the film played by Dennis Hopper.

A proponent of gonzo journalism, Page produced nine books, most of them about Vietnam and its long and often painful aftermath, including a short, brilliantly-written railway travelogue titled Derailed in Uncle Ho’s Victory Garden in 1995.

His best work is probably Requiem, a weighty volume he co-produced with Associated Press lensman and Vietnam veteran Horst Faas containing photographs taken by the cameramen and journalists killed in the Indochina wars, including some from North Vietnamese Army archives.

Still among the missing are Page’s close friends, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, who disappeared along the Vietnam-Cambodia border in April 1970 and are thought to have been eventually executed by the Khmer Rouge near Kampong Cham, northeast of Phnom Penh.

Read by Time Page for Asia Times: A camera’s story of a lost war-time friend

A 1991 film, Danger on the Edge of Town, chronicled his decades-long search to discover their fate, which worried friends say sometimes verged on an obsession. It brought him back to Asia on frequent trips and gave him the idea for Reqiuem, in which Flynn’s pictures are prominently displayed.

He was a familiar face in Hanoi, where officials reportedly called him the Vietnamese equivalent of Mr Ganja because he smoked marijuana openly, claiming his doctors thought it helped him with the after-effects of the wounds he had suffered.

In 2009, Page was named United Nations Photographic Peace Ambassador and was attached for a while to the UN Assistance Mission in Kabul, teaching photography to young Afghans.

One of his students, Barat Ali Batoor, has since settled in Australia where he won the 2013 Nikon-Walkley Photo of the Year for a dramatic image he took on a refugee boat in an unsuccessful attempt to sail from Indonesia to Australia.

Published last year, Page’s final book, Nam Contact, is another massive 448-page coffee table work, essentially contact sheets of previously unseen black-and-white Vietnam war pictures accompanied by text to explain the military operation Page was covering at the time.

It will serve as a fitting epitaph to a one-of-a-kind citizen of the world who turned the wartime experiences of his youth into a life-long stream of photographic consciousness and, in the end, a reminder that war is not so glamorous after all.