An accident leaves a young woman stranded in a hostile country, where she is rescued by a handsome army officer.

They fall in love but must cross several hurdles – including the line that divides their countries – before they can be together.

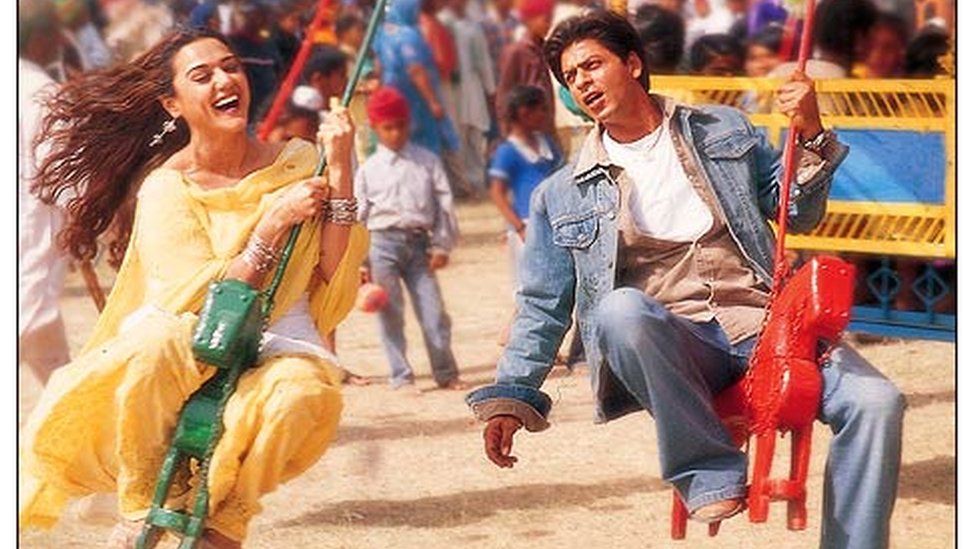

If you narrated this story to an Indian a few years ago, their first thought would probably have been the 2004 Bollywood film Veer-Zaara, starring Shah Rukh Khan and Preity Zinta as star-crossed lovers from India and Pakistan, neighbouring countries that share a tense relationship.

That is, until the 2019 Korean drama Crash Landing On You (CLOY) swept in with a similar premise – centred around neighbours South and North Korea – but with wildly different results.

“The world loved CLOY because the show made the sadness shared by the two countries so palpable and accessible. But I feel South Asians around the world felt it differently,” says Paroma Chakravarty, who co-hosts a K-drama podcast called Drama Over Flowers.

Her podcast – one of many – is an indication of just how popular K-dramas are in India now. The country’s K-drama love began in the north-eastern state of Manipur after separatist rebels banned Bollywood films in 2000, and slowly spread across the rest of the country. It got a fillip in 2020, when the pandemic kept people inside their homes – K-drama viewership on Netflix India surged by more than 370% that year from the previous one.

It’s tempting to draw comparisons between the burgeoning love for K-dramas – which seem to be getting both more inventive and realistic in their storytelling – and changing viewership trends for Bollywood, India’s massive Hindi film industry which is still struggling to get back to pre-pandemic highs.

But it’s hard to compare them like for like, says Supriya Nair, editor of the weekly publication Fifty Two and a K-drama fan.

“Popular Hindi cinema, like popular Korean cinema, is made primarily for male audiences; popular Korean TV, like popular Hindi TV, is made for women,” she says.

But there are several similarities between the two entertainment industries, both famed for their melodramatic, over-the-top romances.

Like Bollywood, K-dramas create an immersive world of their own. The laws of the universe don’t always apply here, and plot lines can ricochet between starkly realistic and mind-bogglingly over-the-top. Both are massive industries with millions of viewers and an intense fandom.

“Like with other forms of mass entertainment from around the world, [Bollywood is] comfortable with genre mixing and high-low tones: we can take slapstick, action, romance, magical realism and poetic interiority in the same narrative,” Ms Nair says.

And Korean shows offer the same storytelling agility – fairy-tale endings are almost always guaranteed but it takes several twists and turns to get there.

But the deepest similarities between them are the familial and social hierarchies depicted in these stories. Korean dramas are able to “articulate the death grip that parents have over children that no one in the West will be able to understand the way we do”, Ms Nair says.

Plot lines in Korean shows and Bollywood films frequently revolve around the impact this has on protagonists – from choosing who they can love, the careers they can pursue, the obligations women have to their husband’s household and the social net provided by families.

“But while the reality is regressive, I also think the best dramas are able to treat this with unprecedented tenderness, thoughtfulness and forgiveness for everyone involved – including our own less-than-radical selves,” Ms Nair says.

Even when it comes to courtship on screen, the two industries sometimes overlap.

“Romantic love is idealised and its pursuit is sweet and innocent,” Ms Chakravarty says. “This is something Bollywood has been moving away from for a few years, so a lot of Indian viewers are moving on to K-drama rom coms.”

For instance, Ms Nair says that fans of Tamil, Malayalam and Telugu films would find a lot of resonance with a K-drama like Hometown Cha Cha Cha.

“It follows a plot that southern Indian filmmakers have loved for decades: an ambitious city girl moves to a scenic village where she gets taken down a peg by the locals and finds love with a schlub.”

But these similarities also mean that the two industries veer towards the same mistakes, particularly in their portrayal of romantic love – romanticising stalking, forceful physical grabbing of women, and infantilising heroines.

“Jealousy is shown as a sign of love, and men monopolising their girlfriend/wife’s time is shown as deep devotion,” Ms Chakravarty observes.

K-dramas and Indian movies also tend to forgive evil family members by the end, she says. And stories of domestic abuse are rarely handled well in both industries.

But for many Indian women, the biggest attraction of Korean shows is its treatment of heroines. Irrespective of genre, these leading ladies are often smart and complex, with a story arc that explores their life outside of romance and aren’t just a foil for the hero.

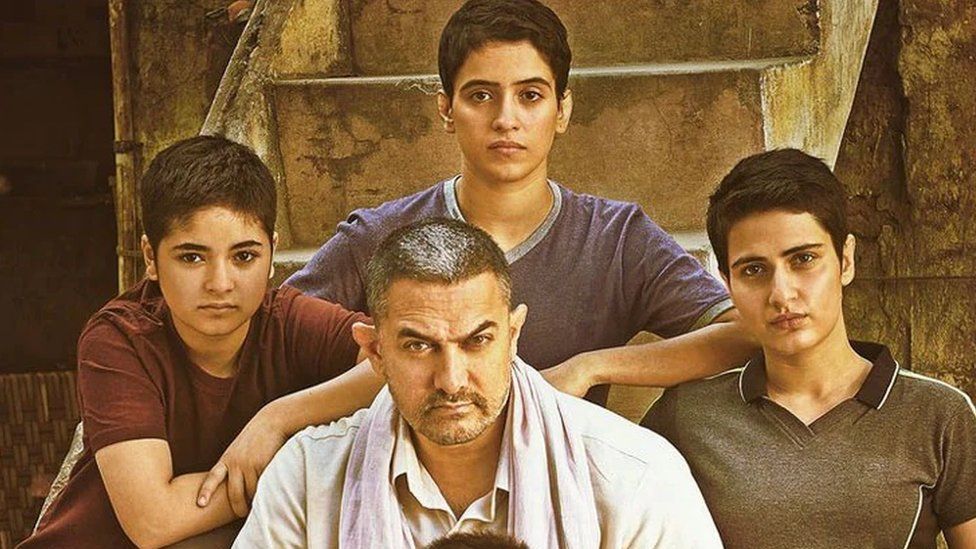

Take, for instance, the superhit Bollywood film Dangal and the Korean drama Weightlifting Fairy Kim Bok-joo – both released in 2016 and tell the stories of female athletes.

But Dangal, headlined by superstar Aamir Khan, chooses to foreground the sacrifices made by a father to make his daughters successful wrestlers. On the other hand, the K-drama puts its protagonist, a young female weightlifter, front and centre.

Both tell a story of courage, rebellion and sacrifice, but where Dangal ultimately requires the daughters to submit to their father’s judgement, Weightlifting Fairy focuses on the internal struggles of the young athlete.

With many of their hit shows written and directed by women, Korean showrunners are able to “adhere to severely conservative norms and broadcast standards” while being “on the side of women’s ambitions and their personal freedoms”, Ms Nair says.

So while Dangal ultimately harnesses Khan’s star power to produce a spectacle, Weightlifting Fairy’s focus remains firmly on its leading lady and her growth as a character.

It helps that K-dramas often tell their story through 16 episodes – “a novel with 16 chapters” as Ms Chakravarty calls them.

Ms Nair says it’s exciting to see the agency given to women in K-dramas.”Have you noticed how many sageuks [Korean period dramas] are anachronistic fantasies about women’s freedom?” she says.

“We never make those in Indian pop culture because not even in fantasy can we allow women to behave freely outside the bounds of caste and religious mandates.”

Part of this is connected to relative freedom from religious and social stratification that occurred in Korea, China and other parts of east Asia over the 20th century, she says.

Long-time K-drama watchers credit the inventive storytelling in these shows to the industry’s emphasis on good scriptwriters, many of whom are women. A similar respect for the craft and skills of the scriptwriter could transform how Bollywood tells stories, they say.

And Crash Landing On You is a good example of how to make difficult stories palatable and sensitive.

“Even though many of popular Hindi cinema’s biggest stars and filmmakers suffered partition directly, I don’t think they or their descendants have been able to depict the idea of mutual love with the same success as Koreans have,” Ms Nair says.

“It’s ironic because the Koreas have been at war for 70 years and India and Pakistan have had extended periods of peace in the same time.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

- Why half of India’s urban women stay at home

- Bitter divisions over Ukraine dominate G20 talks

- The Indian-American CEO who wants to be US president

- India anti-corruption crusader fighting to clear his name

- Ukraine war casts shadow over India’s G20 ambitions

- The self-styled preacher raising fears in India’s Punjab

-

-

16 October 2021

-

-

-

27 March 2022

-