The economic agenda was equally important to Beijing, given the difficulties China is currently facing.

Given the nature of Australia-China trade, there is a limit to the punitive measures China can impose on Australia. In fact, despite the tensions that existed with Australia under the Morrison government, overall bilateral trade has continued to grow, reaching nearly A$300 billion (US$192 billion) in 2022. This shows how complementary the two economies actually are, as well as the resilience of these economic ties.

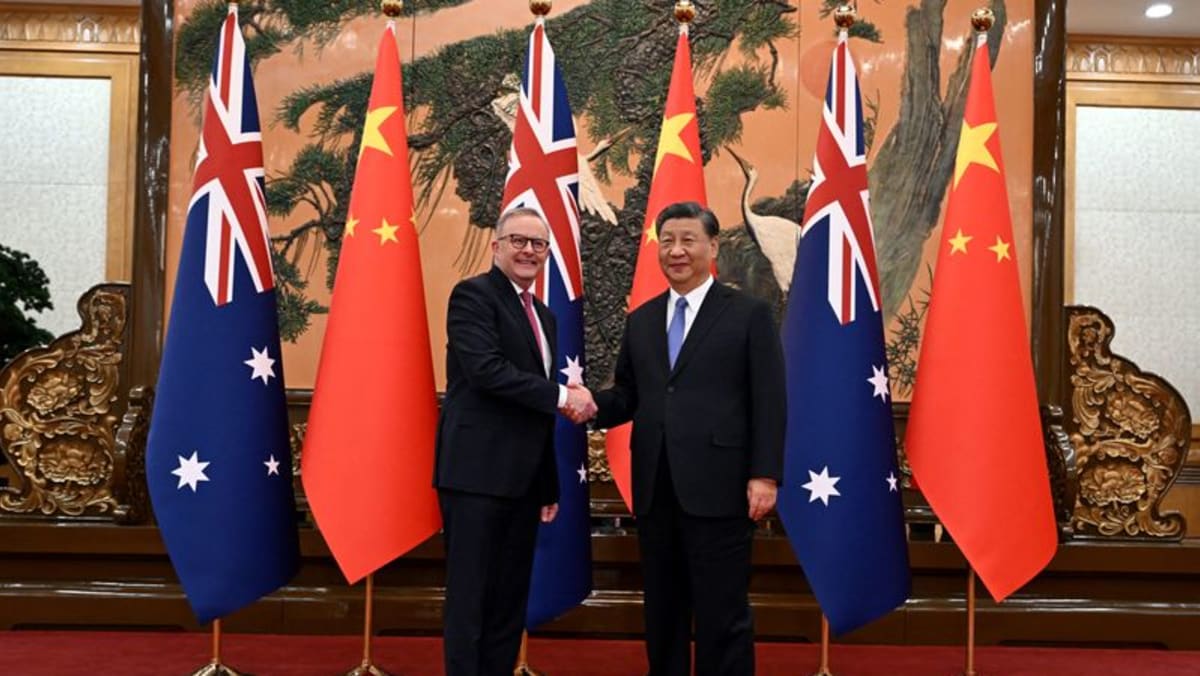

This is what Chinese leaders and the media emphasised during Albanese’s visit and why they were highly critical of the idea of “decoupling” or “de-risking” from China’s economy.

They characterised “decoupling” as going against free trade and protectionism, but in reality, Beijing is deeply concerned over any specific measures that restrict trade in the high-tech sector, such as with semiconductors. The US and its allies have been increasingly adopting such restrictions in recent years.

THE IMPORTANCE OF WHAT WASN’T SAID

What wasn’t discussed much in the Chinese media was the gap between what Beijing presented as a successful visit and what was actually achieved.

One could argue both sides talked about the obvious – for example, that bilateral relations have more or less stabilised, compared to how they were 18 months ago. As China expert Richard McGregor astutely observed, Albanese was “pushing on an open door”.

This is not to belittle the progress made so far. The intention of both governments to resume and strengthen the many dialogues between officials from their countries is important – even critical – in “resetting” the relationship. These channels of communication are incredibly important during times of crisis as a way of managing disputes and avoiding conflicts from spiralling out of control.

Though resetting the relationship was a definite aim in the long term, there were also significant takeaways in the short term. This can be seen in how the state media coverage downplayed AUKUS and conflicts in the South Pacific, where China’s influence has raised alarm bells in Canberra and Washington.

China has signalled its displeasure over AUKUS and continues to consider it a major impediment to further improvement of bilateral relations. But Xi told Albanese they could work together on regional security challenges.

Where there are efforts to cause disturbances in the Asia-Pacific region, we must firstly stay vigilant, and secondly oppose them.

And in the Pacific, the Chinese side is seeing an opportunity for the two countries in terms of regional economic development – how Australia and China can both contribute.

Jingdong Yuan is Associate Professor of Asia-Pacific Security at the University of Sydney. This commentary first appeared on The Conversation.