Why is it needed?

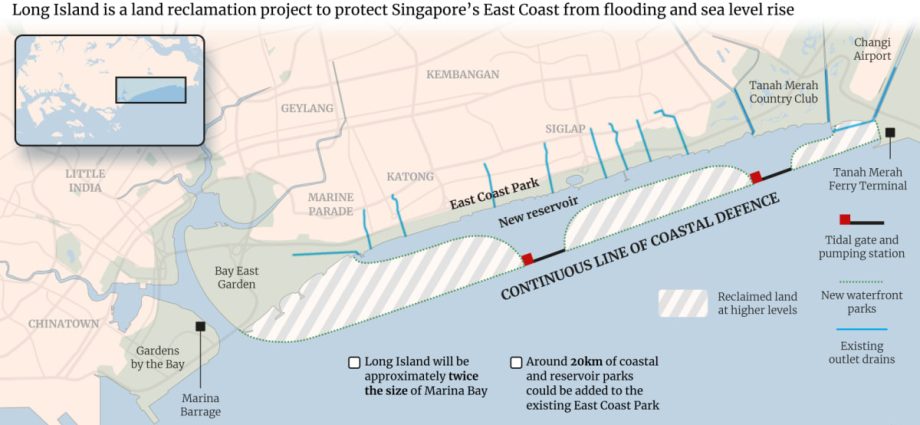

Coastal protection measures are at the heart of the Long Island plan.

Studies have projected a rise in mean sea level of up to 1m by 2100. Combined with possible high tides and storm surges, sea levels could rise by 4m to 5m, threatening low-lying Singapore’s shorelines.

Since 2021, Singapore has studied different parts of its coastline and in September it launched a research centre for coastal protection and flood management.

Around one-third of Singapore – including East Coast Park – is less than 5m above mean sea level. And the effects of high sea levels at the park – Singapore’s largest, with a span of about 13km – are already being felt. In 2018 and in January this year, swathes of the park were flooded due to rain and high tide.

Solutions such as a 3m-high sea wall along the entire waterfront of East Coast Park are not ideal: This would limit access to the beach and sacrifice a substantial portion of the park.

The authorities thus settled on Long Island as a more optimal solution.

Hasn’t Singapore reclaimed land before?

Yes. The country is no stranger to creating new land from the seas – in particular along its eastern coast.

For instance, the East Coast Reclamation Scheme was launched in 1966 and carried out over seven phases, at a total cost of S$613 million. It reclaimed a total of 1,525 ha of land.

Material for the reclamation came from hills in Bedok and Tampines, and sand was also sourced from overseas.

The reclaimed land was used largely for commercial and residential purposes, with Marine Parade the first housing estate to be built entirely on reclaimed land.

East Coast Park and East Coast Parkway were also born from this reclamation.