In conversations about China’s market, the issue of populations comes up quite a lot. In 2022, China’s population , began to decrease , ( and coincidentally, India’s population , surpassed China’s ). The government’s fertility rate, which had already fallen below replacement rates years previously,  , fell suddenly late, to only 1.09 , — one of the lowest rates in the world, and also lower than Japan.

This is prompting a lot of hands- shaking about the future of China’s business, both from citizens within China and from unusual spectators. For instance,  , how’s a phrase in the WSJ:

” As the population mountains, China is showing signs of Japanification”, Yin Jianfeng, deputy director of the National Institution for Finance and Development, a express- backed consider container, wrote in an essay published in June. Yin urged the Chinese government to invest more in education and child rearing to prevent Japan’s demise, which has endured centuries of stagnation.

These ‘s , The Analyst:

China’s economy threats shrinking, also, as a result. The state sensations a near-imminent disaster because it has a lot of attention ahead, and China is getting older before it becomes wealthy. In 2008, when Japan’s people started to fall, its GDP per person was previously about$ 47, 500 in today’s money. China’s is only$ 21, 000. Less of that money will be available for the working generation to eat or invest because more of it is spent on preserving older citizens.

And here’s the most severe post I could discover, from , The Conversation:

As lower production begins to change production in certain sectors, China may be forced to raise imports to meet the demand in those sectors, which could have a significant impact on innovation and innovation, which could further reduce productivity.  , New ideas…drive economic development. The labor size has an impact on innovation because as the number of employed people shrinks, the lake of fresh ideas shrinks. If population growth is bad or at zero, the understanding behind those suggestions stagnates.

Additionally, there is proof that the highest peak of a person’s modern activities and academic output occurs between the ages of 30 and 40. Current demographic trends are known to stifle technological advancements and innovation in China. This reduces the economy’s vitality and causes slower economic growth.

Then, I absolutely , do  , think , this is a concern for China in the long term. In fact, China is far from unique in this regard — every developed country is aging rapidly, and most developing countries are n’t far behind.

And there really , are  , adverse effects to population ageing. In this post, I addressed those issues.

In fact, the shrinking of the population is n’t really the problem — it’s the , aging. Working people are under a lot of financial strain as a result of rising old-age dependency rates, and an aging workforce likely reduces innovation and productivity development. This is true despite technology. A world where younger people must work harder and harder all over the world will be a universe where old people will be the most prevalent.

But in the short term, I think the catastrophizing over China’s populations is overdone. Americans who are desperate to find a reason to ignore China’s dynamic threat might be drawn to the country’s lower fertility. But China’s economic might is not going to go “poof” and disappear from population aging, in fact, as I’ll explain, it probably wo n’t suffer significant problems from aging until the second half of this century.

However, there’s an even greater danger that China’s leaders will stress over the country’s demographics and do something really impulsive. In response to my former Bloomberg colleague Hal Brands, who claimed that China may start a war in Asia in the coming years out of concern that its influence will decline if it waits any longer. This is similar to how Germany went to war in 1914 because its leaders believed their window was closing. That worry is unfounded, as I’ll show. But it would n’t be the first , rash blunder that Xi Jinping has made.

Therefore, understanding the non-epidemic nature of China’s demographic situation would be beneficial for both Americans and Chinese citizens.

China has a baby bulge in the pipeline

The first and most significant factor in China’s demographics is that there are many young people, between the ages of 5 and 15, who will relieve demographic pressure in the upcoming years.

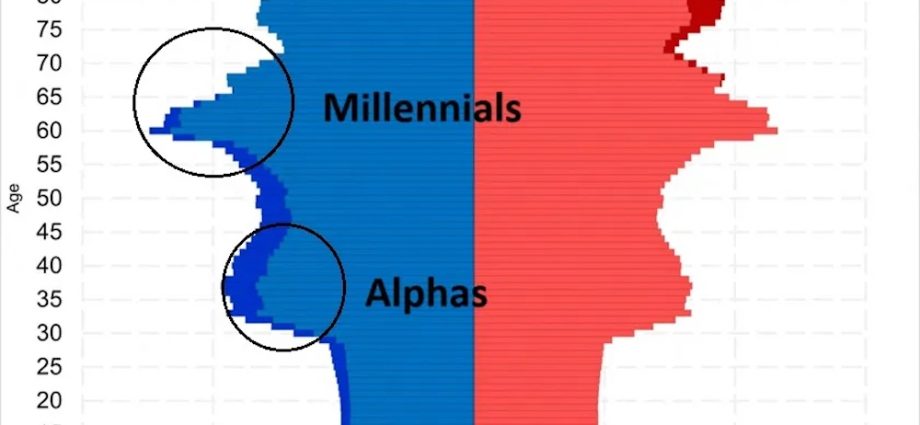

Wikipedia has a good , animated population pyramid , for China, with data taken from UN forecasts. Here’s what the pyramid looks like for 2024. Generation labels, roughly corresponding to the similar generations in the United States, have been added to the graph.

As you can see, China’s current young working generation — the Zoomers — are a small generation. But the generation younger than that — the Alphas, currently aged 5 to 15 — are a bigger generation than the Zoomers.

China’s Alphas are not a true “baby boom” in the classic sense — there was no surge in fertility rates 5 to 15 years ago. Instead, the Alphas are a , demographic echo , of the large Millennial generation, which is itself an echo of China’s extremely large Baby Boom generation. The US had a fertility rate of 3.5 during its Baby Boom,  , China’s was over 6. China is a major Alpha country because there were so many Boomers in the 1960s.

Anyway, as the Alphas reach working age over the next decade, they will stabilize China’s demographics. China’s working- age population is actually projected to , increase , over the next few years, before beginning a slow decline:

As Charlie Robertson , has shown, this will stabilize China’s dependency ratio at a very favorable level through the end of the decade:

China’s dependency ratio in 2030 will still be as good as Japan’s at the height of its economic miracle. Only by mid- century will China’s ratio deteriorate to the level of Japan’s in 2020.

So aging basically wo n’t be a problem for China’s workforce until mid- century. Around 2050, things start to look worse. No significant young generation will be joining China’s large Millennial generation as they age out of the workforce:

This forecast assumes, of course, that the post- pandemic plunge in Chinese fertility rates does n’t bounce back within the next decade. That remains to be seen. But whatever happens, China’s demographic structure is unlikely to have major problems for a quarter century.

China has the ability to make up for aging in the near future.

Even though China’s demographics do n’t get severe until 2050 or so, it will still experience gentle aging over the next 26 years. Its median age is expected to increase from 39.5 to 50.7:

After 2027 or so, China’s working- age population will start to decline, and its dependency ratio will start to worsen.

None of this spells catastrophe, for reasons laid out in the previous section. But it does present a challenge. There are a few relatively simple policies that China can use to make up for its short-term effects of aging, fortunately.

First, and most importantly, it can , raise the retirement age. The country currently has the world’s lowest retirement age — just 60 for men and 50- 55 for women. Simply changing this to 65 will decrease the dependency ratio significantly, and reduce the burden on working people. In fact, China reportedly , plans to do this:

Jin Weigang, president of the Chinese Academy of Labor and Social Security Sciences, said China was eyeing a “progressive, flexible and differentiated path to raising the retirement age”, meaning that it would be delayed initially by a few months, which would be subsequently increased.

According to the Global Times, “people who are approaching retirement age will only have to delay retirement for a few months,” according to Jin. Young people may need to work a few more years, but they will also have a protracted period of adjustment and transition, he said.

China has already used the second policy to boost college enrollment, according to the report. In 2010, only 26.5 % of college- aged Chinese people were enrolled in postsecondary education, by 2023 , that increased to 60.2 %.

As every labor economist , knows, a better- educated workforce is a more productive workforce. The Gen Xers and older Millennials who will retire in China over the next quarter century are not very well educated. The Alphas, the replacement employees, have a very high level of education. That will make up for a large portion of the population under the age of working.

China should experience few issues from the gentle demographic headwinds of the next two and a half decades because of the large youth cohort, raising the retirement age, and sending a lot more kids to college. Its leaders still need to think about the long-term demographic challenge after 2050, but the majority of its rivals are even worse off.

Overall, the idea that demographics will shift China’s position of economic and political power away from it in the coming decades seems overblown and unrealistic. The rest of the world will be concerned about more competition as a result. However, it also means that China wo n’t be able to compete internationally in the near future.

Footnote:

1 Many people will claim that China can also use automation to make up for the country’s declining human labor and move more people to cities. I’m skeptical of both of these. Regarding the first of these,  , the finding , that aging , decreases productivity , holds true , despite , significant automation over the last few decades.

So automation helps, but it does n’t fully plug the gap yet ( though perhaps with better AI it will ). As for moving more workers to cities, official statistics claim that China’s urbanization rate lags that of other developed countries, but , satellite evidence shows , that China is already more densely urbanized than Germany.

So I do n’t see much upside there. But in any case, I do n’t think China , needs , these factors to offset aging over the next 25 years — increased education and a higher retirement age should be enough to take care of it.

This , article , was first published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack and is republished with kind permission. Read the original here and become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.