China is closing, destroying and repurposing mosques, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has alleged in a new report.

The crackdown is part of a “systematic effort” to curb the practice of Islam in China, HRW said.

There are about 20 million Muslims in China, which is officially atheist but says it allows religious freedom.

Observers, however, say there has been an increased crackdown on organised religion in recent years – with Beijing seeking greater control.

The BBC contacted China’s foreign ministry and ethnic affairs commission for comment in advance of publication of the HRW report.

“The Chinese government’s closure, destruction and repurposing of mosques is part of a systemic effort to curb the practice of Islam in China,” said Maya Wang, acting China director at Human Rights Watch.

The report follows mounting evidence of systematic human rights abuses against Uyghur Muslims in China’s north-western Xinjiang region. Beijing denies the accusations of abuse.

Most of China’s Muslims live in the country’s north-west, which includes Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia.

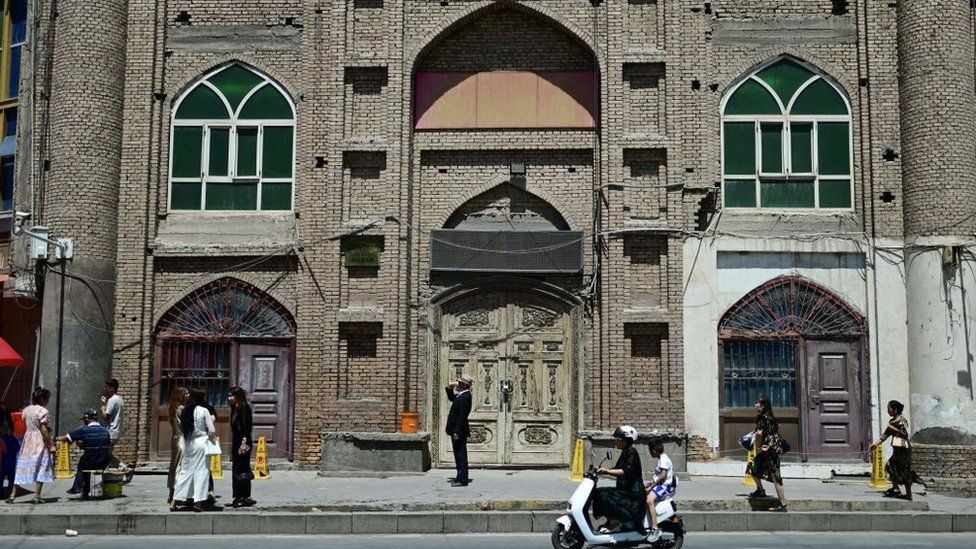

In the Muslim-majority village of Liaoqiao in the autonomous region of Ningxia, three of six mosques have been stripped of their domes and minarets, according to HRW. The rest have had their main prayer halls destroyed, it said.

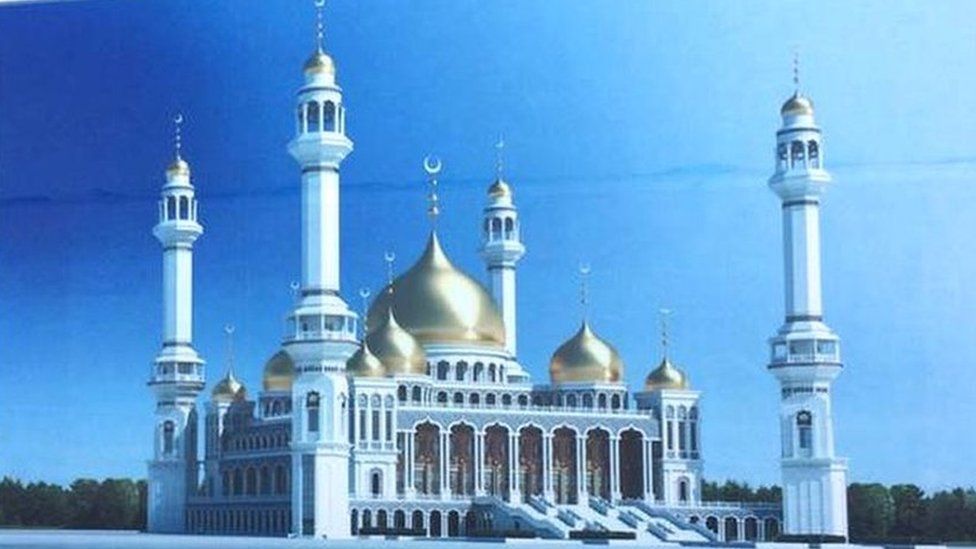

Satellite footage obtained by HRW showed a round dome at a mosque in Liaoqiao village being replaced by a Chinese-style pagoda sometime between October 2018 and January 2020.

About 1,300 mosques in Ningxia have been closed or converted since 2020, Hannah Theaker, a scholar on Chinese Muslims, told the BBC. That number represents a third of the total mosques in the region.

Under China’s leader Xi Jinping the Communist Party has sought to align religion with its political ideology and Chinese culture.

In 2018, the Chinese Communist Party’s central committee published a document that referred to the control and consolidation of mosques. It urged state governments to “demolish more and build fewer, and make efforts to compress the overall number” of such structures.

The construction, layout and funding of mosques must be “strictly monitored”, according to the document.

Such repression has been most longstanding and severe in Tibet and Xinjiang, but it has also extended to other areas.

There are two major Muslim ethnic groups in China. The Huis are descended from Muslims who arrived in China in the 8th Century during the Tang Dynasty. The second group is the Uyghurs, mostly residing in Xinjiang. About two-thirds of the mosques in Xinjiang have been damaged or destroyed since 2017, according to a report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, an independent think-tank.

“Generally speaking, Ningxia has been a pilot site for implementation of the ‘Sinicisation’ policy, and hence, both renovations and mergers appear to have begun in Ningxia ahead of other provinces,” says Dr Theaker, who is co-writing a report on Hui Muslims with US-based academic David Stroup.

“Sinicisation” refers to Mr Xi’s efforts to transform religious beliefs to reflect Chinese culture and society.

The Chinese government claims the consolidation of mosques – which often happens when villagers are relocated or combined – helps reduce the economic burden on Muslims, but some Hui Muslims believe it is part of efforts to redirect their loyalty towards the Party.

Some residents have publicly opposed these “Sinicisation” policies, but their resistance has so far been futile. Over the years, many have been jailed or detained after clashing with authorities over the closure or demolition of mosques.

After removing external elements from mosques, local governments would then remove facilities essential for religious activities such as ablution halls and preacher’s podiums, according to US-based Hui activist Ma Ju.

“When people stop going [to the mosques, the authorities] would then use that as an excuse to close the mosques,” he is quoted as saying in the Human Rights Watch report.

Another video verified by HRW showed an ablution hall in Liujiaguo mosque in southern Ningxia being demolished shortly after the removal of its two minarets and a dome.

In Gansu province, which shares a border with Ningxia, officials have made periodic announcements of mosques being closed down, consolidated and altered.

In 2018, authorities banned minors under 16 from participating in religious activities or study in Linxia, a city in the province previously known as China’s “Little Mecca”. A 2019 report by a local television station said authorities converted several mosques into “workspaces” and “cultural centres” after “painstaking ideological education and guidance work”.

Before the “Sinicisation” campaigns, Hui Muslims have in many ways been receiving support and encouragement from the state, said Dr Theaker.

“The campaign has radically narrowed the space in which it is possible to be Muslim in China, and thrown the weight of the state behind a very particular vision of patriotism and religious observance.

“It reflects the profoundly Islamophobic orientation of the state, in that it requires Muslims to demonstrate patriotism above all, and views any sign of ‘foreign’ influence as a threat,” she said.

Arab and Muslim leaders across the world should be “asking questions and raising concerns”, said Elaine Pearson, Human Rights Watch’s Asia director.

Other ethnic and religious minorities have also been affected by the government’s campaign.

For instance, Beijing has in recent months replaced the use of “Tibet” with “Xizang” – the region’s name in Mandarin – on official diplomatic documents. The authorities have also removed crosses from churches, arrested pastors and pulled Bibles from online stores.

-

-

1 September 2022

-

-

-

18 December 2018

-

-

-

15 August 2018

-