Isro

IsroIndia recently announced a host of ambitious space projects and approved 227bn rupees ($ 2.7bn, £2.1bn ) for them.

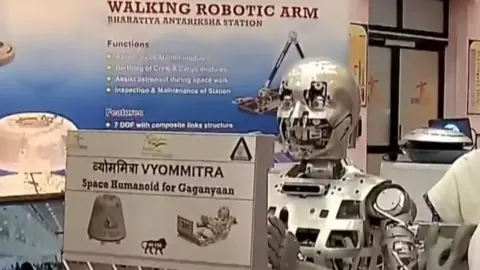

The programs include the construction of India’s traditional space station, sending an spacecraft to Venus, and creating a fresh, reusable, heavy-lifting rocket to launch satellites.

Although it is the largest allocation of funds to area projects ever made in India, they are not spectacular and have once again highlighted the cost-effectiveness of the country’s space program.

Experts around the world have marvelled at how little Indian Space Research Organisation’s (Isro) Moon, Mars and solar missions have cost. India spent $74m on the Mars orbiter Mangalyaan and $75m on last year’s historic Chandrayaan-3 – less than the $100m spent on the sci-fi thriller Gravity.

Nasa’s Maven orbiter had cost $582m and Russia’s Luna-25, which crashed on to the Moon’s surface two days before Chandrayaan-3’s landing, had cost 12.6bn roubles ($133m).

Despite the low cost, scientists say India is punching much above its weight by aiming to do valuable work.

Chandrayaan-1 was the first to confirm the presence of water in lunar soil and Mangalyaan carried a payload to study methane in the atmosphere of Mars. Images and data sent by Chandrayaan-3 are being looked at with great interest by space enthusiasts around the world.

How does India manage to keep the prices so small?

Screenshot from Doordarshan

Screenshot from DoordarshanSisir Kumar Das, a retired civil servant who oversaw Isro’s funds for more than 20 years, claims that the prudence dates back to the 1960s, when scientists second presented a space program to the state.

India was struggling to serve its inhabitants and maintain adequate hospitals and schools, and it had only been granted independence from British colonial rule in 1947.

Vikram Sarabhai, the founder of Isro and scientist, had to persuade the state that a space program was not just a powerful comfort that had no place in a poor nation like India. He explained to the BBC that spacecraft could improve the way India serves its members.

But India’s space programme has always had to work with a tight budget in a country with conflicting needs and demands. Photographs from the 1960s and 70s show scientists carrying rockets and satellites on cycles or even a bullock cart.

Years later and after several successful interstellar missions, Isro’s funds remains modest. This year, India’s budgetary allocation for its space programme is 130bn rupees ($ 1.55bn )- Nasa’s budget for the year is$ 25bn.

According to Mr. Das, the key factor in why Isro’s operations are so inexpensive is that all of its equipment is made in India and its technology is developed locally.

In 1974, after Delhi conducted its first nuclear test and the West imposed an sanctions, banning transfer of technology to India, the limits were “turned into a blessing in disguise” for the space program, he adds.

” Our scientists seized it as a motivating factor for the development of their own technologies.” All the tools they needed was produced locally, and labor costs and pay were noticeably lower in this country than in the US or Europe.

Isro

IsroAccording to research author Pallava Bagla, Nasa outsources dish production to private businesses and also takes out plan for its operations, which add to their costs, in contrast to Isro.

” Also, unlike Nasa, India does n’t do engineering models which are used for testing a project before the actual launch. We only have one unit available, and it’s designed to travel. It’s difficult, there are possibilities of accident, but that’s the risk we take. And we are able to get it because it’s a state programme”.

Mylswamy Annadurai, commander of India’s first and second Moon operations and Mars vision, told the BBC that Isro employs much fewer people and pays lower wages, which makes American jobs dynamic.

He claims that because they were so excited about what they did, he “led small, dedicated team of less than 10 and people frequently worked extended periods without any extra pay.”

The small budget for the jobs, he said, often sent them back to the drawing board, allowed them to consider out of the field and led to new innovations.

” For Chandrayaan-1, the allocated resources was$ 89m and that was fine for the initial design. However, it was later decided that the aircraft would need to transport a Moon effect probe, which may add 35 kg.

Scientists had two options: carrying the mission with a heavier spacecraft, which may cost more, or removing some of the equipment to lighten the load.

Getty Images

Getty Images” We chose the second choice. We decreased the number of tension vehicles and batteries from two to one, and the number of jets from 16 to eight.

Reducing the number of capacitors, Mr Annadurai says, meant the release had to take place before the end of 2008.

The aircraft may have two years while orbiting the Moon without experiencing a protracted solar eclipse, which would have an effect on its potential to recharge. Therefore, in order to satisfy the release date, we had to stick to a strict job schedule.

Mangalyaan value but small, Mr Annadurai says, “because we used most of the equipment we had previously designed for Chandrayaan-2 after the next Moon vision got delayed”.

Mr. Bagla calls India’s affordable area program” an incredible feat” because it comes at such a low cost. But as India scales off, the cost may fall.

At the moment, he says, India uses small rocket launchers because they do n’t have anything stronger. But that means India’s spaceship take much longer to reach their destination.

But, when Chandrayaan-3 was launched, it orbited the Earth many times before it was sling-shot into the solar circle, where it went around the Moon a few times before takeoff. On the other hand, Russia’s Luna-25 escaped the Earth’s gravity fast riding a strong Rocket jet.

” We used Mother Earth’s inertia to push us to the Moon. We needed months of meticulous planning. This is something that Isro has mastered and effectively accomplished.

But, Mr Bagla says, India has announced plans to send a manned mission to the Moon by 2040 and it would need a more powerful rocket to fly the astronauts there quicker.

The government recently said work on this new rocket had already been approved and it would be ready by 2032. This Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV) will be able to carry more weight but also cost more.

Additionally, according to Mr. Bagla, it’s possible that the cost of opening up the space industry will be so minimal once that happens.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.