Burning mangrove trees for a living: ‘I’d quit tomorrow if I could’

Indonesia has more mangrove trees than any other country but there’s growing concern about the “dangerous” rate they are being cut down, turned into charcoal and exported to places such as Europe, China and Japan. People involved in the work know the trees are important for the environment and would like to quit but they see no other way to survive.

Inside a wooden hut, near his house on the island of Borneo, Nurhadi keeps two furnaces burning all year round. The 68-year-old employs at least a dozen people.

Four men cut up wood collected from mangrove trees, while another throws it into a furnace made from earth and stones. Once burned, the wood is cooled and packaged, ready to be sold.

Mangrove wood is very hard and dense but not very durable, which makes it ideal for charcoal production and particularly good for barbeques. But it is a resource-intensive process with little return.

Sixteen tonnes of raw material only produces three tonnes of charcoal. “If I produce less than three tonnes, it’s a loss,” Nurhadi says. Once costs are taken into account, he estimates he only makes a profit of about $1,250 (£1,000) per year.

“There’s no money in cutting down mangroves. Nobody gets rich from charcoal furnaces. We do this to have food on our plate,” he explains.

A conversation he once had with a government official sums up his predicament: “He asked me: ‘Are you ready to leave the charcoal business?’ I answered: ‘If you can provide farming land or other opportunities, I’d quit tomorrow.'”

Almost half of the 9,000 people in Nurhadi’s village, Batu Ampar, rely on mangrove charcoal for a living, a tradition dating back to the 1940s. Some families like Nurhadi’s have been doing this for generations – his father and grandfather owned the same furnaces, so he says this is the only work he knows.

Indonesia is home to 20% of the world’s mangroves, and Nurhadi’s area, the Kuba Raya Regency has the biggest mangrove forest in the western part of Indonesian Borneo.

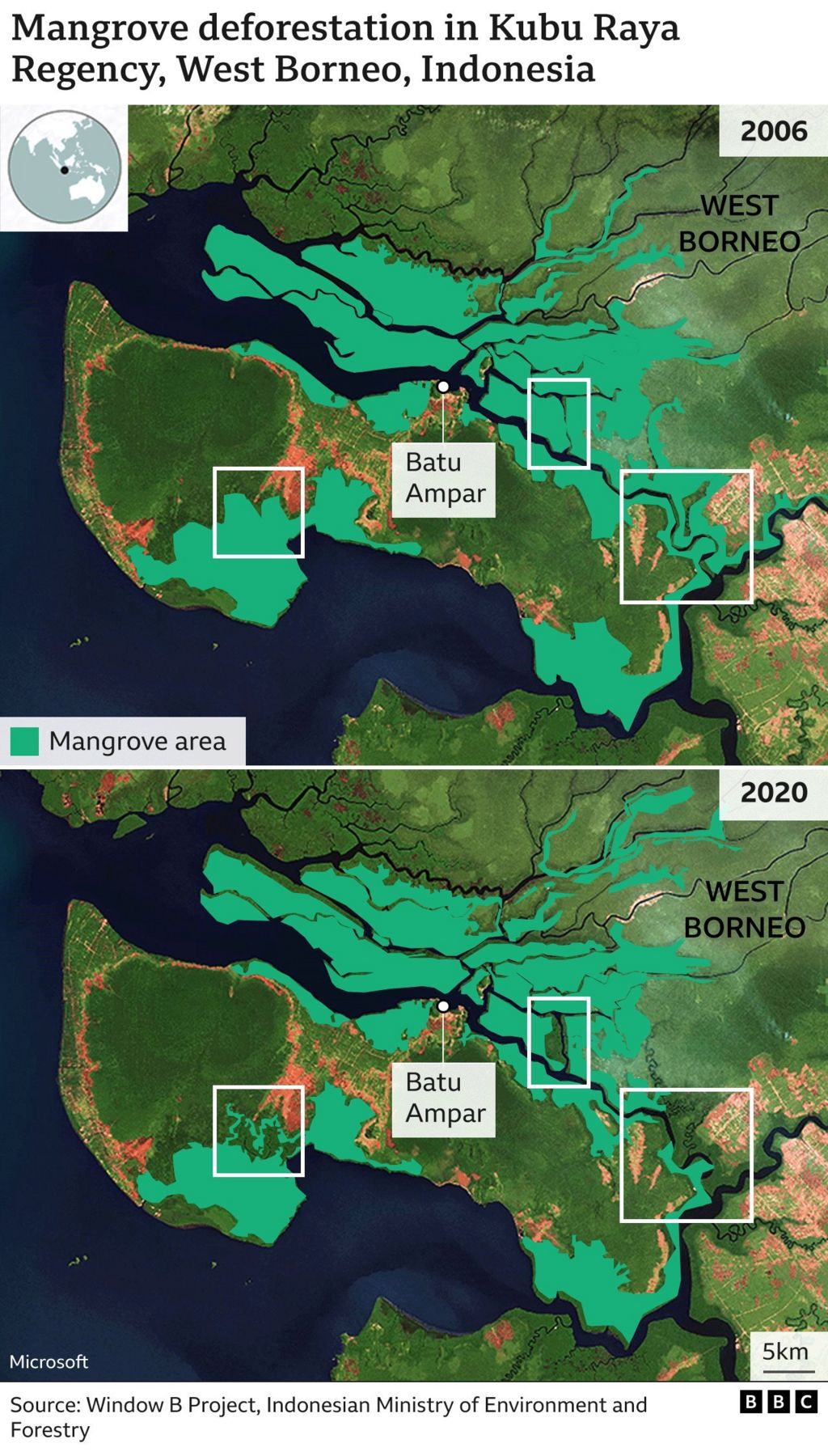

But the number of furnaces is increasing – in 2000 there were 90 but today there are at least 490 – and that is speeding up deforestation.

Arsyad Al Amin, who is involved in a local research project, predicts that the Batu Ampar mangrove forest will only last for another 74 years if things carry on as they are. “It will all be gone in 2096,” the researcher from the Bogor Agricultural Institute says.

Thick, dense forest areas of mangrove canopy have decreased so much that bare patches can now be seen from planes overhead.

“If there is no effort to accelerate rehabilitation, this is dangerous. We desperately need intervention,” he warns.

Mangrove forests:

- Tackle climate change, by reducing carbon in the atmosphere – some do this up to 10 times better than forests on land

- Protect people from coastal erosion, storm surges and tsunamis

- Provide nurseries for tropical fish

- Shield coral reefs from storms and heat waves

- Boost economies of many developing countries

Source: The Ocean Agency

Deep in the forest, an hour north of Batu Ampar village by boat, dozens of mangrove trees have been cut down. The people living along the river breathe in air mingled with the smoke coming from rows of furnaces.

There are areas in this forest where it is legal to take wood, but as the number of furnaces grows, it gets harder to source raw materials and loggers venture further into the protected areas.

Among the sound of monkey chatter and birdsong is the unmistakable sound of a chainsaw revving up.

We speak to some men who are cutting down an average-sized mangrove tree. “We would not cut down the big trees,” says one lumberjack who refuses to reveal his name because he is operating in a protected forest. He’s wearing minimal safety gear. “A logger died from being crushed by wood when cutting,” he says. “This is a high risk job, but my children need to eat.”

The local environment and forestry agency claims it’s been hard to enforce the regulations on illegal logging.

“There are too many home furnaces and a large number of locals involved in this activity,” spokesman Adi Yani says.

He also thinks that if they impose the rules strictly “it has the potential to cause social unrest”.

“Repressive law enforcement” was carried out a few years ago against loggers and furnace owners in Batu Ampar village, says an official with the local government, Herbimo Utoyo. But, he adds, “it never reached court because it is viewed as a tradition, a culture”.

He also says the government has offered to train people how to farm honey from the forest and produce palm sugar to try to move them away from the charcoal industry, but he admits: “It hasn’t been successful yet. It’s hard to break something that has been done from generation to generation.”

But one man who quit the charcoal business says the government needs to do more. “We feel like we were left alone without the government’s support. If they do have programmes, maybe they only came to the head of the village. No-one came to us,” 39-year-old Suheri says.

Ten years ago, he used to run two furnaces but decided to stop after a peatland fire smothered his village in smoke. “I thought that if the fire happened in our mangrove forest, we’d be devastated,” he explains.

Before the pandemic, he tried farming mud crab in mangrove aquaculture, but the venture failed. “I suffered a huge loss, and I am in debt because of it,” he says. Now he collects honey from the forest’s bees instead.

Suheri uses his boat to navigate the waterways and can spend hours looking for beehives that are ready to be harvested.

When he spots one, he puts on a homemade hat with a veil, climbs up the tree and uses smoke from burned nipah leaves to distract the bees. “There are many risks with collecting honey – mud, wild animals, snakes and crocodiles. The least of the risks is getting stung by the bees,” he says with a little laugh.

If he is lucky, Suheri can collect up to five bottles of honey in a day, with one bottle of raw, wild forest honey selling for $10 (£8). It’s a very good price but he says he can’t count on just honey for a living because “the harvesting season is uncertain”.

When he’s not in the forest looking for honey, Suheri breeds croaker fish but the eggs are expensive and there is a high chance they will die.

Even thought it’s not easy, he says he is determined to find something other than the furnaces to make money, in the hope it inspires others in his village to stop cutting down mangrove trees to make charcoal.

“I have to do better… If I want people to change, I have to succeed!” he exclaims.