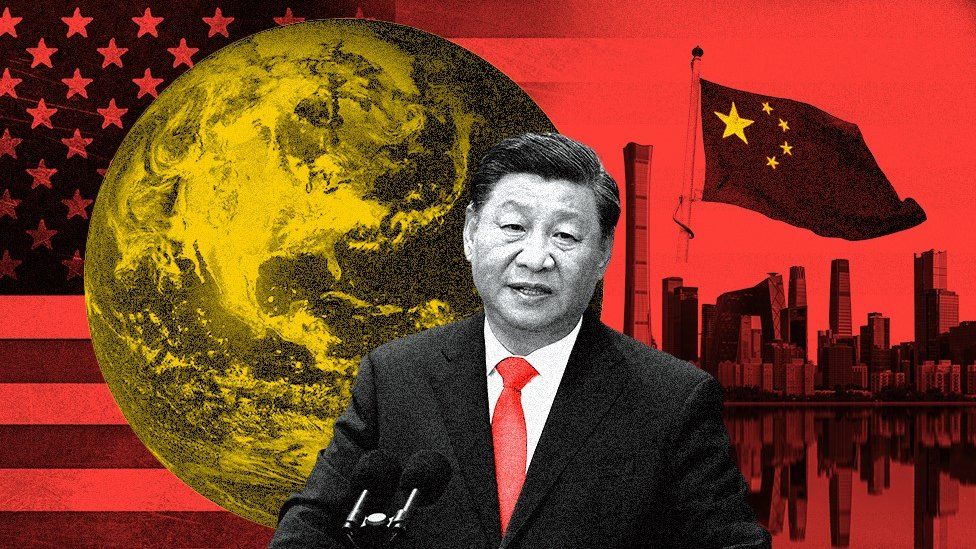

Ten days ago Xi Jinping walked out in front of the world’s media – depleted somewhat by his government’s growing intolerance of foreign reporters – as the most powerful Chinese leader in decades.

A tradition that limited his recent predecessors to two terms had been broken. And third term in hand, he had cemented his power over China, perhaps indefinitely.

But even as Mr Xi’s grip tightens at home, on the international stage the situation has rarely looked more unsettled.

The more the Communist Party leader has reinforced China’s authoritarian model, the more he has challenged a defining assumption of our age of globalisation – as China got richer, it would become freer.

That assumption drove decades of trade and engagement between Washington and Beijing.

It was the bedrock for an economic partnership that would eventually see more than half a trillion dollars’ worth of goods cross the Pacific Ocean every year.

Now as Mr Xi begins his third term, he faces an ongoing trade war with the US and a fresh attempt to deny China access to high-end American chip-making technology that, according to some commentators, is designed to slow China’s rise “at any price”.

Beijing argues that the recent, marked chill in relations is being driven by America’s desire to maintain its position as the pre-eminent world power.

President Joe Biden’s newly released National Security Strategy defines Beijing as a bigger threat to the existing world order than Moscow. And Washington has begun to talk about a Chinese invasion of democratic Taiwan as an increasingly realistic prospect rather than a distant possibility.

This is a long way from the days when both US and Chinese leaders would declare that mutual enrichment would eventually outweigh ideological differences and tensions between an established superpower and a rising one.

So how did we get here?

‘Habits of liberty’

It’s no small irony that it is President Joe Biden who is increasingly treating China as an adversary. And his attempt to cut off its access to advanced semiconductors is arguably the most significant reversal of the trade and engagement approach.

In the late 1990s, Mr Biden, then a member of the US Senate, was a key architect of the efforts to welcome China into the World Trade Organization (WTO).

“China is not our enemy,” he told reporters on a trip to Shanghai in 2000 – a statement based on the belief that increased trade would lock China into a system of shared norms and universal values, and help its rise as a responsible power.

WTO membership – which became a reality on President George W Bush’s watch – was the crowning glory of a decades-old policy of growing engagement, supported by every president since Richard Nixon.

Corporate America too had been lobbying hard for China to open up further, with the likes of British American Tobacco keen to sell to Chinese consumers, and the US-China Business Council eager for access to a cheap, compliant labour force.

For American unions worried about blue-collar job losses, and for anyone concerned about human rights, China’s WTO membership was justified on ideological grounds.

Mr Bush, then the governor of Texas, perhaps put it best in a speech to Boeing workers on the presidential campaign trail in May 2000.

“The case for trade,” with China, he said, was “not just a matter of commerce, but a matter of conviction”.

“Economic freedom creates habits of liberty. And habits of liberty create expectations of democracy.”

For a while, China’s growing prosperity really did seem to raise the prospect of at least some limited, political reform. In the years following WTO membership, the internet – like elsewhere in the world – gave Chinese people an opportunity for discussion and dissent previously undreamt of.

Bill Clinton famously suggested that for the Communist Party taming the internet would be like “trying to nail Jell-O [jelly] to the wall”.

Even after Mr Xi began his first term as the party’s general secretary in 2012, international media coverage often focused on the skyscraper-studded skylines, the cultural exchanges and the new middle class as evidence that China was changing in fundamental ways, and for the better.

But there were plenty of clues that, early on in his rule, Mr Xi had identified those fledgling “habits of liberty” not as a welcome consequence of globalisation, but as something to be fought against at all costs.

Document Number 9, reportedly issued by the Communist Party’s central office just a few months into his first term, lists seven perils to be guarded against, including “universal values”, the concept of a “civil society” beyond party control, and a free press.

Mr Xi believed that it was ideological weakness and a failure to hold the socialist line that led to the downfall of the Soviet Union.

The ideal of shared, universal values was for him a Trojan Horse that would lead the Chinese Communist Party to go the same way, and his answer was swift and uncompromising – an unashamed reassertion of authoritarianism and one-party rule.

Jell-O on the wall

By the time of his second term, China had begun firmly nailing the Jell-O to the wall, imprisoning lawyers, muzzling dissent, snuffing out Hong Kong’s freedoms and building camps for the mass incarceration of more than a million Uyghurs in its far western region of Xinjiang.

Yet there’s little evidence that Western governments were in a hurry to ditch their support for trade and engagement, let alone switch to a policy of actively curtailing China’s rise, as Beijing now claims.

For decades, China’s WTO entry offered huge profits for corporations that lined their supply chains with Chinese labour, and a new frontier for businesses to sell to Chinese consumers. Embassies have long been staffed – and many still are – with trade teams numbering in the hundreds.

The UK’s so-called “Golden Era” with China – a tub-thumping endorsement of the trade and engagement mantra – was launched during Mr Xi’s first term and continued into his second.

It even saw a UK chancellor travel to Xinjiang, by then already the focus of serious human rights concerns, for a photo opportunity specifically to highlight the trade opportunities on offer in the region.

I watched George Osborne, wearing a hi-viz vest, unloading a lorry a short drive away from the prison in which the prominent Uyghur intellectual Ilham Tohti had recently begun his life sentence.

While visiting politicians from democratic states have always trumpeted the benefits of engagement, human rights were more often raised “behind closed doors”.

During the same period, Hunter Biden – the youngest son of the president – forged business relationships with Chinese entities with ties to the Communist Party, a connection that is at the centre of the political controversy swirling around him till today.

With hindsight, there’s little evidence that American or European political elites were eager to re-evaluate the engagement approach.

During my time in Beijing, corporate executives would often tell me that my journalism covering China’s growing repression somehow missed the point by not capturing the bigger picture of growing prosperity.

It was as if, instead of opening the minds of Chinese officials to the idea of political reform as promised, trade and engagement had instead changed the minds of those in the outside world, gazing in at the skyscrapers and high-speed rail links.

The lesson seemed to be not that economic freedoms and political freedoms went hand in hand, but that you could have all of this wealth without any human rights at all.

One senior manager for a US multinational household-products brand with large investments in China told me that “Chinese people don’t want freedom” in the way people in the West do.

He’d spoken to workers in his factories, he insisted, and he’d concluded they had no interest in politics at all. “They’re happier earning money,” he said.

Somewhere along the way many of the traders and engagers – corporations and governments alike – seemed to have simply dropped the lofty promise of bringing political freedom to China.

Increasing prosperity now seemed to be enough on its own.

So, what changed?

Breaking the mould

Firstly, public opinion. From 2018 onwards, the Uyghur diaspora began to speak out about the disappearance of their family members into Xinjiang’s giant prison camps, despite the clear risk that doing so might bring further costs and punishments for those relatives back home.

China at first seemed shocked by the international reaction.

After all, Western governments had long tolerated many facets of Beijing’s repression while continuing to trade and engage.

Even before Mr Xi took office, the targeting of religious belief, the jailing of dissidents and the brutal enforcement of the one-child policy were an integral part of the political system, not a mere side effect.

But the mass incarceration of the Uyghurs – with an entire people designated a threat solely on the basis of their culture and identity – had a big impact on global public opinion because of its historic resonances in Europe and beyond.

Corporations with supply chains in Xinjiang were facing the mounting concern of consumers, and governments were coming under increasing political pressure to act.

There were other issues too – including the swiftness with which Beijing has crushed dissent in Hong Kong, its militarisation of the South China Sea and the growing threats over Taiwan.

But Xinjiang seemed to crystallise thinking and China too could feel the tide turning – it is no accident that many of the international journalists trying to uncover what was happening in Xinjiang have since been forced out of the country, myself included.

The latest Pew opinion survey finds that 80% of Americans now have an unfavourable opinion of China, up from just 40% or so a decade ago.

The second significant factor that changed things was Donald Trump.

Donald Trump’s anti-China message may have been characteristically erratic – with his allegations of unfair trade practices tempered by his open admiration of Mr Xi’s strongman-style – but he used it to rally a disaffected blue-collar base with great effect.

In short, he claimed that trade and engagement had been a bad bet with little to show for it, other than outsourced jobs and technology.

His opponents criticised his counter-productive methods and what they saw as his xenophobic language, but the mould had been broken.

President Biden has walked back few, if any, of Mr Trump’s policies on China, including the trade war he launched. The tariffs have stayed.

Washington has come to belatedly realise that, far from speeding up political reform in China, trade and technology transfer has been used instead to bolster Beijing’s authoritarian model.

A new normal

There is no clearer indication of just how profound a shift has taken place in US-China relations than President Biden’s recent comments on the status of Taiwan.

Last month he was asked by CBS News if US forces would be sent to defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion.

“Yes,” he said, “if in fact there was an unprecedented attack.”

The official policy in Washington has long been one of deliberate strategic ambiguity over whether it would come to Taiwan’s aid. Admitting that the US wouldn’t intervene, the argument went, might give the green light to an invasion. And saying it would mount a defence might encourage Taiwan’s self-ruled government towards a formal declaration of independence.

The new, apparent “strategic clarity” has been met with fury from Beijing, which sees it as a major readjustment in the US position.

It’s hard to disagree, despite attempts by senior US officials to walk back the comments.

Instead of shared norms and values, China now offers its model of prosperous authoritarianism as a superior alternative.

It is working hard in international bodies, through its intelligence services, and its vast propaganda outreach to promote its system, while arguing that democracies are in decline.

In some quarters – the German business community for example – the argument in favour of trade and engagement has taken on an altogether different tone.

China is now so important to global supply chains, and so powerful, the new case being made is that we have no choice but to continue trading, for fear of harming our own economic interests or provoking a “backlash” from Beijing.

But in Washington, the view that China presents a serious threat has become one of the few topics of strong bipartisan consensus.

There may, as yet, be no easy alternatives – supply chains would take years to relocate and doing so will be expensive.

And China does have the means to reward those who continue to engage while imposing costs on those who don’t.

But what is undoubtedly true at the start of Mr Xi’s third term is that the world is in a moment of profound change.

And in China, as in Russia, America finds itself confronted by an adversary largely of its own making.

Read more of our coverage of Xi Jinping’s China

-

-

1 July 2021

-