Framed by steel girders and bricks, a floor-to-ceiling glass façade looks onto lotus-strewn wetlands where buffaloes wallow in Hoi An, the ancient trading port of central Vietnam.

As a visitor turns under the beat of high ceiling fans, an outsize 1210mm camera lens stares back at them through the black steel sliding door. This is the Imaginarium of Boris Zuliani, also known as Black Hands Studio, where the entire studio is itself a massive functioning camera shooting photographic images directly onto glass panes as large as 2x2m.

“I like the fact that this is a difficult process, the need for specific chemicals, the precise handling of the glass plates, the need to work fast,” said Zuliani, sharing his fascination with this demanding technique. “We must combat threats of potential failure on so many fronts, so each shot is truly a one-off with its own character.”

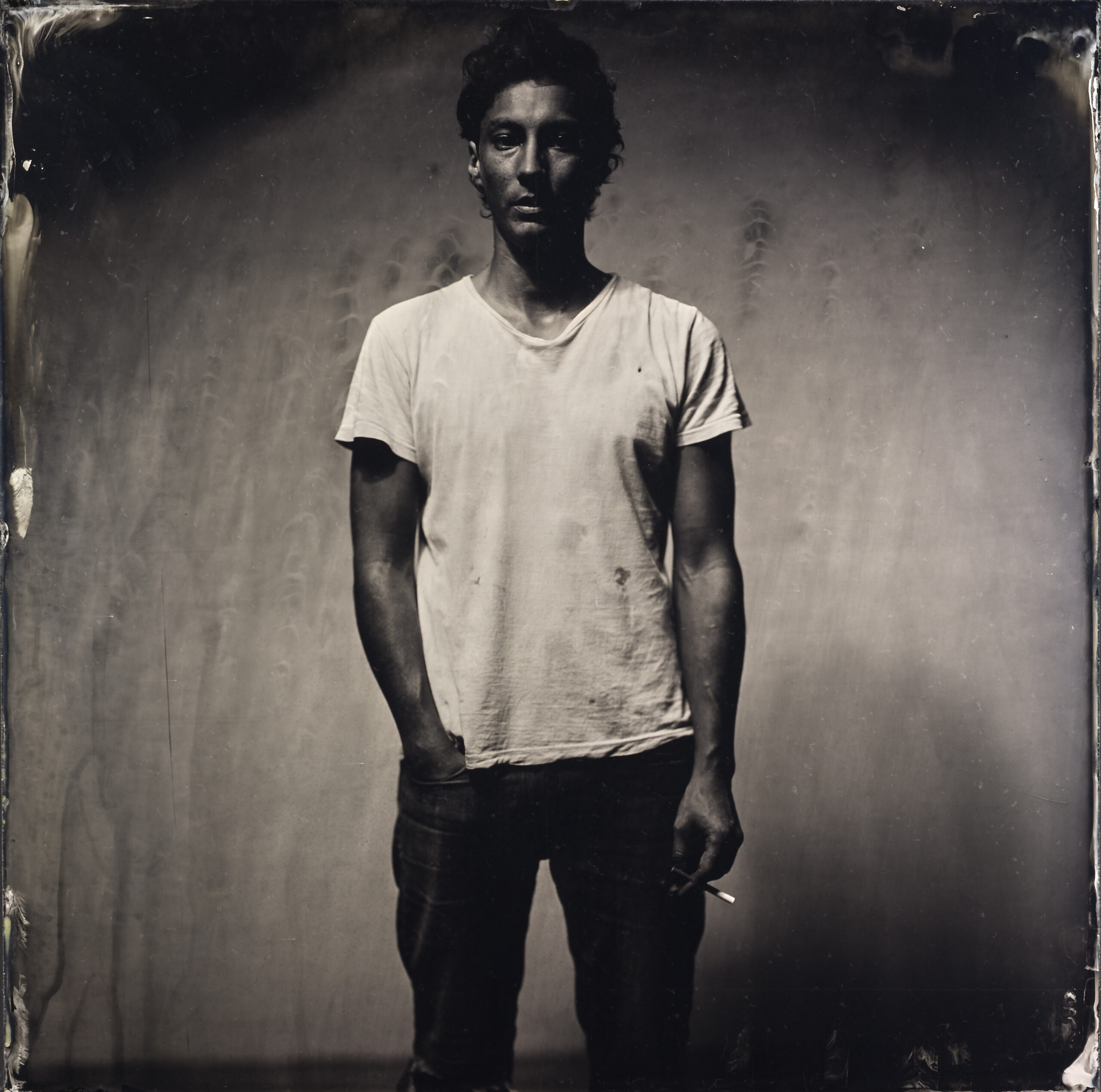

He refers to the final creations as ambrotypes, a word of Greek derivation which roughly translates as an “immortal impression”.

Originally from France, Zuliani has been in Vietnam since 2007 honing his obsession with what he calls “light painting”, pushing the envelope of photosensitive materials to create unique textures and tones with his lens. Based in Hoi An, Zuliani is furthering his mission to defy digitalisation of the photographic arts and create something uniquely retro-analogue.

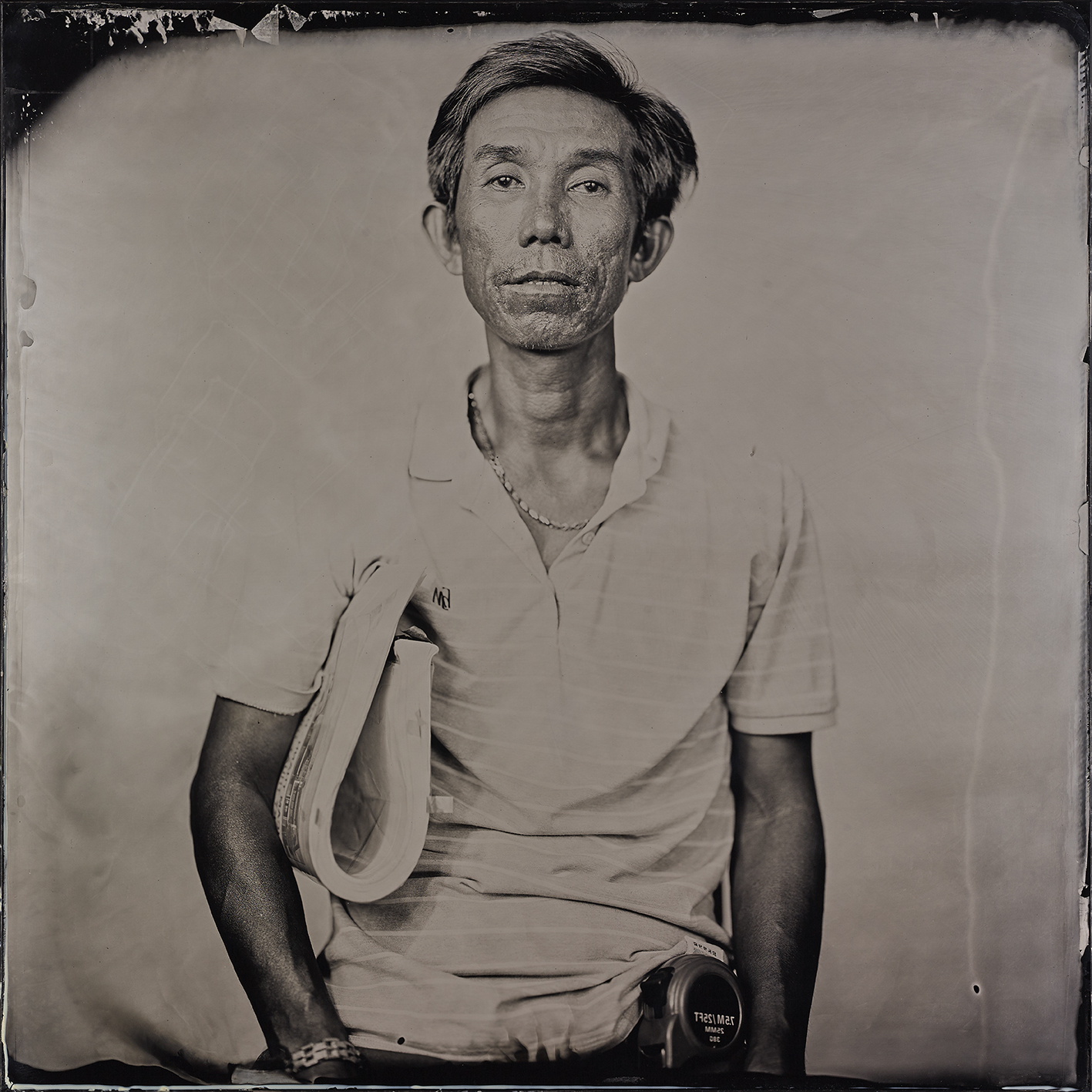

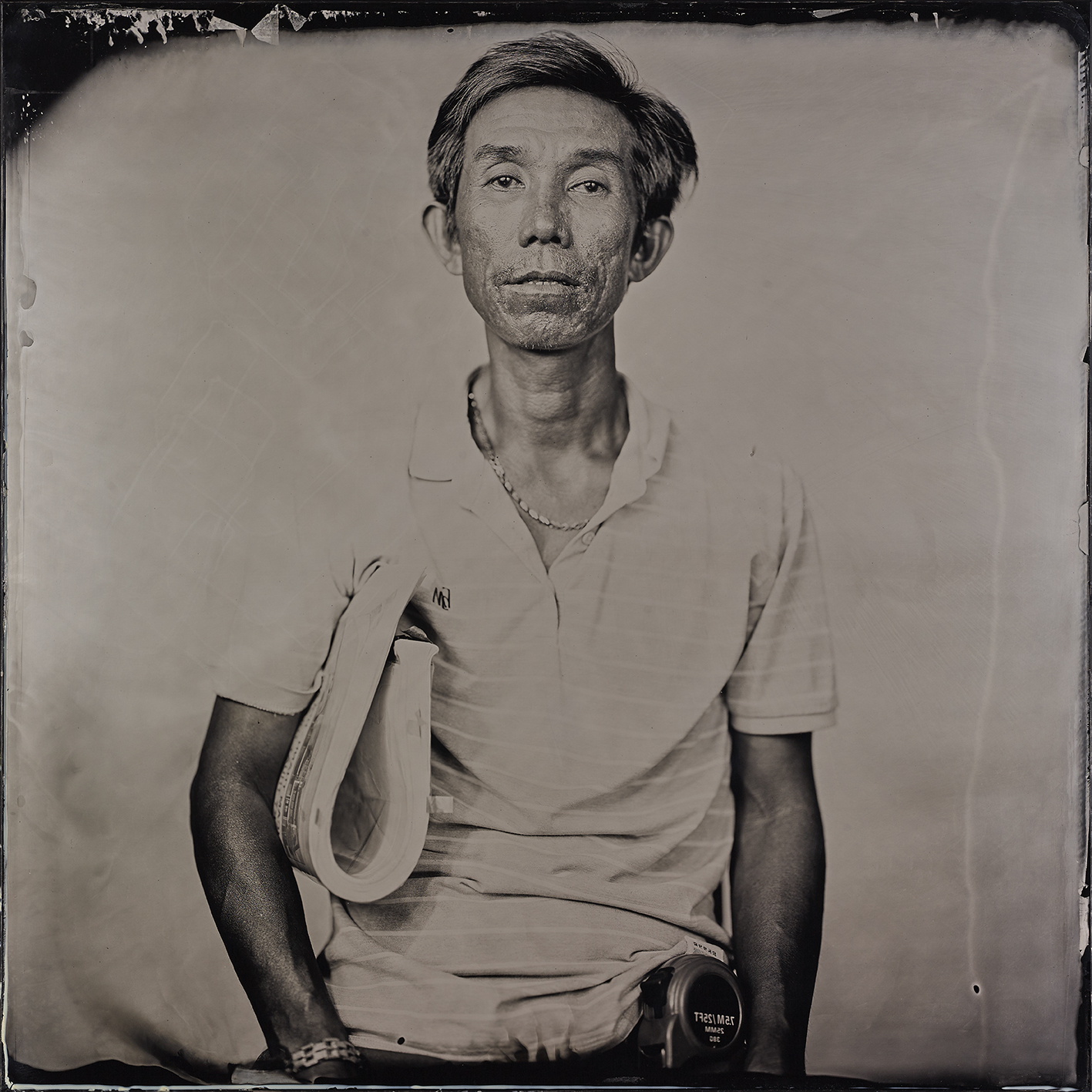

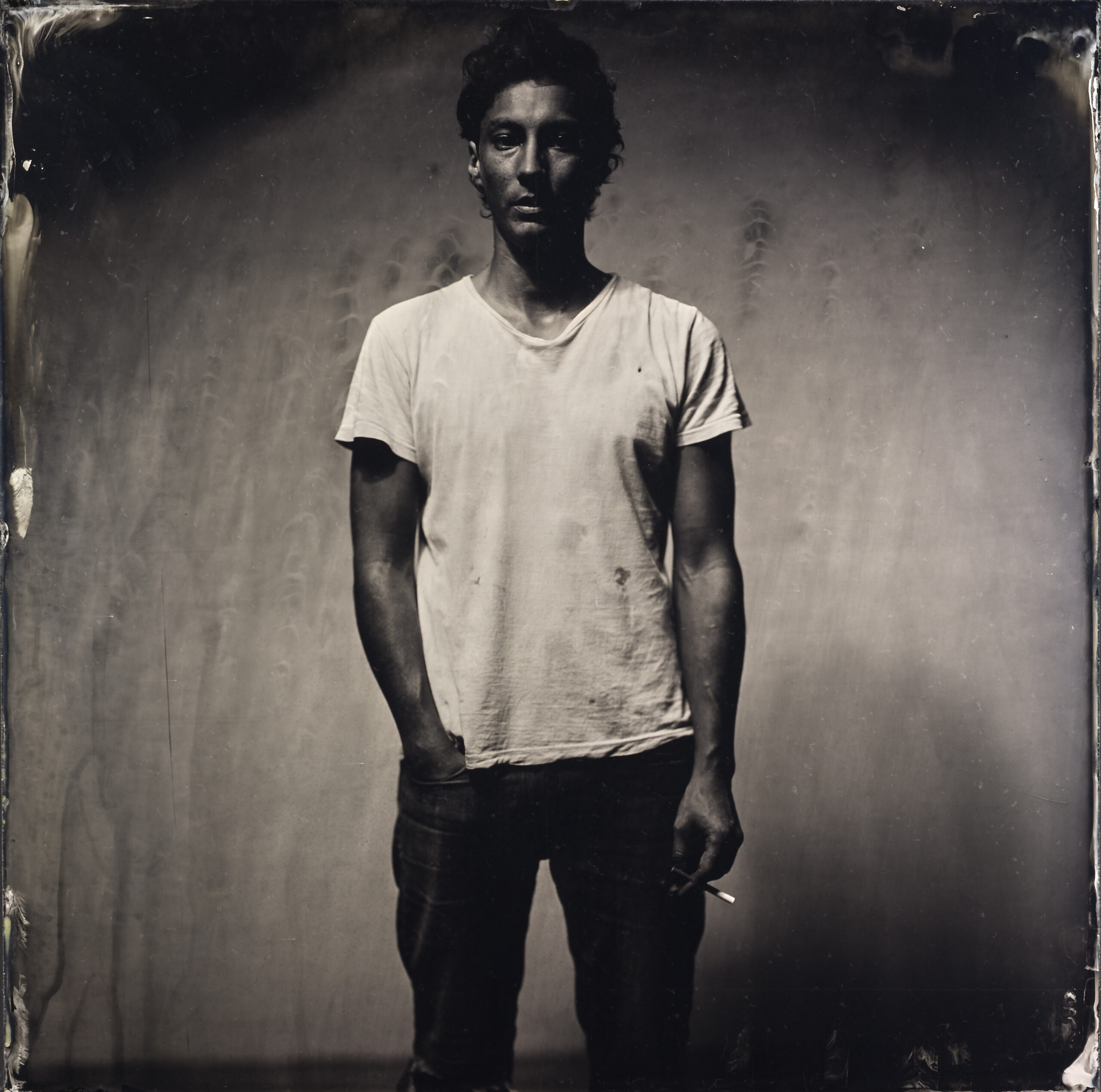

Their current exhibition, WANTED, a series of portraits of Vietnamese workers, is part of that mission. So too is the physical structure of the expansive Black Hands studio, where Zuliani and his team have worked for the past year. There, the lens sits in the door while the subject poses in the main room. Light comes through the lens and onto the glass plate positioned in the darkroom, where the ambrotype is made.

It’s the kind of technique that has helped Zuliani stand out in Vietnam.

Even as he first settled into the photography scene there, his style caught the attention of Nguyen Qui Duc, the creative force behind Hanoian cultural space Tadioto.

The 2009 exposition Les Mots Bleus featured works Zuliani shot on Polaroid film exposed via a self-made pinhole camera, and then enlarged onto canvas which filled the walls at Tadioto’s gallery.

“Over the past 15 years, I have seen Boris continually challenge the limits of his materials. Whether shooting onto polaroid, canvas or glass plates, it’s his exacting professionalism and mad genius innovation that has remained constant as he strives to create his art,” said Duc.

As a journeyman photographer, Ziuliani was initially schooled in high fashion precision camera shoots at Studio Des Plantes in Paris. After several years in the business, his imagination was caught by an encounter in Vienna with The Impossible Project, which sought to promote analogue instant film techniques when Polaroid announced it was shutting down production.

“I suddenly realised that Polaroid film had a limited supply, so I bought 5,000 boxes and found myself at the airport en route to Vietnam,” Ziuliani recalled. “When I arrived in Hanoi, the customs authorities could not understand why I had such quantities of film for my own personal use, so that took a lot of explaining for me to get them into the country.”

While working for fashion assignments in the bustling cities of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, he continued to pursue his own artistic output on the side – including a series of moody polaroid portraits of lovers on the Gustav Eiffel-designed Long Bien bridge which spans the Red River on Hanoi’s eastern fringe.

This analogue style would help inform his later works at the Black Hands Studio.

In that space, Zuliani’s rangy studio assistant Hugo Armano casts a long shadow in the afternoon light. His sharp eye and organizational acumen holds the operation together and keeps the studio shipshape.

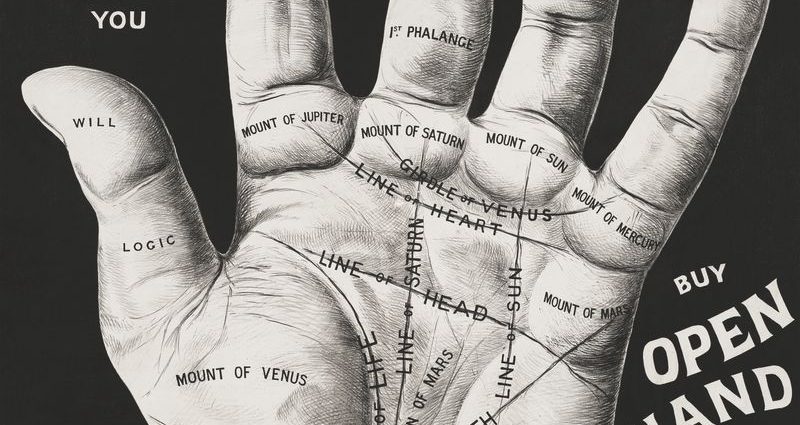

Together the two Frenchmen extract magic from a volatile process approaching alchemy – pouring a stream of collodion by hand to coat individual glass plates before soaking them in a bath of silver nitrate. This is wet plate collodion photography, originally developed by Frederick Scott Archer whose scientific breakthrough in 1848 quickly replaced daguerreotypes and paved the way towards modern photographic techniques.

‘’We named the studio Black Hands because of the chemical residue we would get on our skin,” Armano said, casually noting that one stray drop of silver nitrate could burn through skin in a few seconds.

A very physical series of steps begins with ensuring the plates are perfectly clean before applying chemical reagents in the darkroom. The coated plate is then secured in a sealed wooden box before being loaded into the back of the camera, behind the bellows.

The subject is positionally primed in advance, and after any final adjustments to the framing, the ambrotype is captured onto the glass plate in rich silver and black tones. The end result is an uncanny combination of negative and positive image, which has a varying depth depending at which angle the viewer looks at the finished work.

“We called the current exhibition WANTED partly because the portraits have an element of the American Wild West,” said Zuliani, noting the intersection of that frontier era with the emergence of collodion photography.

The title also reflects the scarcity of supply for artisans and workers with the skills needed to build Kyara Arthouse in central Vietnam, a key partner of Black Hands and the host of its exhibition, as the Covid-19 lockdowns intensified.

“We asked each of them to bring their most important tool with them – you can see such pride in their work etched in their faces,” Zuliani said.

The WANTED collection was shot on 50x50cm glass plates, using a refurbished 150-year-old camera. Initial success with this model found on eBay inspired Zuliani to keep pushing after meeting fellow photographer and skilled carpenter Francis Roux, who had also relocated to Hoi An.

Together they designed an upscaled model, with Roux crafting a bespoke bellows camera housing out of walnut wood, which accommodates a 1x1m glass plate.

‘’Making the 1x1m format camera only made me want to go even further,” enthused Zuliani.

Encouraged by their success, they soon acquired the 1210mm lens to install in the door and expanded to the 2x2m glass plates to complete the Imaginarium – for now.

“We had been working out of such a small garage, so thought why not make the new studio building itself into the housing for a larger-format camera set up,” he said. “It is quite a surreal concept, but when we shoot with the big lens the photographers are inside the camera itself.”

WANTED Photo Exposition: A Collaboration between Black Hands Studio and Kyara Arthouse is on show until May 14th 2023, including over the International Workers Day holidays, at Kyara: 234 Tran Nhan Tong, Cam Thanh Ward, Hoi An, Vietnam.

Web: https://blackhandsstudio.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kyarahoian and Instagram: @kyarahoian @boriszuliani

James Compton is a writer focused on the intersection between arts, culture and nature conservation in Asia. He is based in Hoi An, Vietnam, where he co-manages Kyara Arthouse as a hub for artistic practice and exchange.