Swastik chum

Swastik chumA blogger in India’s Bihar state received a frantic call at home on a quiet Sunday night in November 2005.

” The Separatists have attacked the jail. Citizens are being killed! I’m hiding in the toilet”, an inmate gasped into the cellular phone, his speech trembling. The noise of shots echoed in the background.

He was calling from a prison in Jehanabad, a poverty-stricken city and, at the time, a enclave of left-wing fanaticism.

The crumbling, red-brick, colonial-era jail overflowed with individuals. Spread across an hectares, its 13 camp and tissues were described in formal studies as “dark, wet, and filthy”. Initially designed for around 230, it held up to 800 captives.

The Maoist rebellion, which began in Naxalbari, a village in West Bengal state in the late 1960s, had spread to big parts of India, including Bihar. For almost 60 years, the guerrillas- likewise called Naxalites- have fought the American state to build a socialist society, the movement claiming at least 40, 000 lives.

Mobs were housed in the Jehanabad prison in a powder keg alongside their upper class Hindu private soldiers ‘ vigilantes. All awaited test for common crimes. Like some Indian prison, some residents had access to wireless devices, secured through bribing the soldiers.

” The area is swarming with separatists. Some are” just walking out,” the prisoner, one of the 659 prisoners at the time, said to Mr. Singh.

On the night of 13 November 2005, 389 prisoners, including many rebels, escaped from Jehanabad prison in what became India’s – and possibly Asia’s – largest jailbreak. At least two people were killed in the prison shootout, and police rifles were looted amid the chaos. The United States Department of State’s 2005 report on terrorism said the rebels had even “abducted 30 inmates” who were members of an anti-Maoist group.

Raj Ravi

Raj RaviIn a tantalising bend, police said the “mastermind” of the prison break was Ajay Kanu, a flaming rebel chief who was among the prisoners. According to police, safety was so weak in the tiny prison that Kanu stayed in contact with his prohibited team on the phone and through messages allegedly helped them enter. This is not accurate, says Kanu.

Lots of rebels in authorities uniforms climbed up and down the high walls using wood ladders and crawled inside, opening fireplace from their rifles, and crossed a drying flow behind the jail.

The tissues were empty because the meal was being prepared in the kitchen late at night. The insurgents entered the main walls and opened them. Troops on duty looked on hopelessly. Just 30 of the fugitives were prisoners, and the remainder were awaiting trial. Prisoners escaped by just walking out of the doors and disappeared into the darkness. According to witnesses, it was over in less than an hour.

The widespread jailbreak exposed the crumbling of Bihar’s law and order and the growing Communist rebellion in one of India’s most underprivileged areas. Due to the pending condition votes, the insurgents had perfect timing for their strategy.

AFP

AFP—

Rajkumar Singh, the native journalist, remembers the day brilliantly.

He rode his motorcycle through a lonely city in an effort to get to his office after receiving the call. He recalls that in the range shots ringing in the air were frequent. The attacking rebels were even attempting to attack a nearby police station.

Difficult streetlights awaited him as he turned onto the main street, which flashed through a microphone and flashed a dozen armed men and women in authorities outfits blocking the way.

” We are Mobs”, they declared. ” We’re not against the people, just the government. The hack is portion of our rally”.

Along the way, the insurgents planted explosives. Some were now detonating, collapsing with outside stores, and infuriating the city.

Mr Singh says he pressed on, reaching his fourth-floor department, where he received a second call from the same slave.

” One’s running. What if I perform”?, the inmate said.

” If one’s escaping, you may too”, Mr Singh said.

Then he rode to the prison through the oddly empty roads. When he reached, he found the doors open. The home had rice pudding all over it, and cell phones were locked. No police officer or jailor was visible.

In a place, two wounded police lay on the floor. Mr. Singh claims that he also witnessed the bruised body of Bade Sharma, the head of the feared middle class rebel army of landlords called Ranvir Sena, lying on the ground. Eventually, the police claimed that the insurgents had shot him as they were leaving.

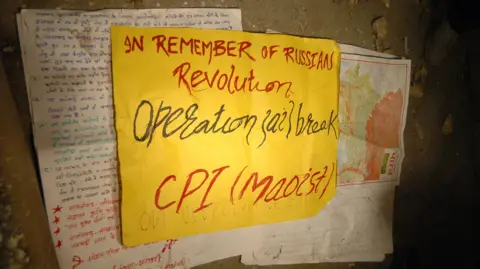

Written papers left behind by the insurgents were strewn on the floor and stowed against the walls.

We want to inform the position and central governments that if they detain the revolutionaries and the oppressed and keep them in jail, they also know how to open them from prison in a Communist revolution way, according to one pamphlet.

Raj Ravi

Raj Ravi—

A few months ago, I met Kanu, the 57-year-old rebel chief the officers accuse of masterminding the hack, in Patna, Bihar’s turbulent money.

At the time of the incident, media reports painted him as “Bihar’s most wanted”, a figure commanding both fear and respect from the police.

Officials recounted how the dissident” captain” immediately took power during the prison split once he was handed an AK-47 by his friends.

In a dramatic change, the reports said, he “expertly” handled the weapons, quickly changing newspapers before allegedly targeting and shooting Sharma. In February 2007, Kanu was detained from a railroad platform in Dhanbad, Bihar, while he was traveling from Kolkata to the city of Dhanbad. Five months later, in February 2007.

In all but six of the 45 initial legal cases brought against him, Kanu has been cleared nearly 20 years after. Most of the circumstances stem from the hack, including that of the death of Sharma. For one of the circumstances, he served seven years in prison.

Despite his dangerous status, Kanu is surprisingly talkative. He speaks in strong, measured bursts, downplaying his position in the large leave that made stories. Today, this once-feared rebel is gently shifting his gaze toward a diverse battle- a career in politics, “fighting for weak, back castes”.

As a child, Kanu spent his days and nights listening to stories from his lower-caste farmer father about Communist uprisings in Russia, China, and Indonesia. By eighth grade, his father’s comrades were urging him to embrace revolutionary politics. He claims that after scoring a goal in a football match against the son of the neighborhood landlord, armed upper-caste men stormed their home.

” I locked myself inside”, he recalls. ” They came for me and my sister, ransacking the house, destroying everything. That’s how the upper castes kept us under control through fear.

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalIn college, while studying political science, Kanu ironically led the student wing of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP), which has waged a war against Maoism. After graduation, he co-founded a school, only to be forced out by the owner of the building. Upon returning to his village, tensions with the local landlord escalated. When a local strongman was murdered, Kanu, just 23, was named in the police complaint- and he went into hiding.

” Since then I have been on the run, most of my life. I left home early to mobilise workers and farmers, joined and went underground as a Maoist rebel”, he said. He joined the Communist Party of India ( Marxist-Leninist ), a radical communist group.

” My profession was the liberation of the poor,” I said. It involved confronting the atrocities of the upper castes. I fought for those enduring injustice and oppression”.

—

With a feared reputation as a rebel leader and a three million rupee bounty on his head as an incentive for people to report his whereabouts if they found him, Kanu was on his way to meet underground leaders and develop new strategies in August 2002.

At a busy intersection, a car overtook him and drove him to where he was going in Patna. ” Within moments, men in plainclothes jumped out, guns drawn, ordering me to surrender. I did n’t resist- I gave up”, he said.

AFP

AFPKanu was shuttled between jails over the course of three years as a result of police fear. ” He had a remarkable reputation, the sharpest of them all”, a senior officer told me. In each jail, Kanu says he formed prisoner unions to protest against corruption- stolen rations, poor healthcare, bribery. In one prison, he led a three-day hunger strike. ” There were clashes”, he says,” but I kept demanding better conditions”.

Kanu paints a stark picture of the overcrowding in Indian prisons, describing Jehanabad, which held more than double its intended capacity.

” There was no place to sleep. In my first barrack, 180 prisoners were crammed into a space meant for just 40. We devised a system to survive. The remaining fifty of us slept for four hours while the others sat, waited, and chatted in the dark. Another group would take their turn as the four hours went on. That’s how we endured life inside those walls”.

In 2005, Kanu escaped during the infamous jailbreak.

When gunfire started to erupt, we were waiting for dinner. Bombs, bullets- it was chaos”, he recalls. ” The Maoists stormed in, yelling for us to flee. Everyone ran into the darkness. Should I have remained silent and been killed?

Many doubt the simplicity of Kanu’s claims.

” It was n’t as simple as he makes it sound”, said a police officer. ” Why was dinner prepared late in the evening when the cells were typically locked up early and cooked and served at dusk?” That alone raised suspicions of inside collusion”.

Interestingly many of of the prisoners who escaped were back in jail by mid-December- some voluntarily, others not. None of the rebels returned.

When I asked Kanu whether he masterminded the escape, he smiled. ” The Maoists freed us- it’s their job to liberate”, he said.

But when pressed again, Kanu fell silent.

As he finally shared a story from prison, the irony grew even more.

He had been questioned by a police officer about his plans for another escape.

” Sir, does a thief ever tell you what he’s going to steal”? Kanu replied wryly.

A man who claims he had no part in the jailbreak’s planning, his words hung in the air.