Several major oil companies, including BP and Shell, periodically publish scenarios forecasting the future of the energy sector. In recent years, they have added visions for how climate change might be addressed, including scenarios that they claim are consistent with the international Paris climate agreement.

These scenarios are hugely influential. They are used by companies making investment decisions and, importantly, by policymakers as a basis for their decisions.

But are they really compatible with the Paris Agreement?

Many of the future scenarios show continued reliance on fossil fuels. But data gaps and a lack of transparency can make it difficult to compare them with independent scientific assessments, such as the global reviews by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

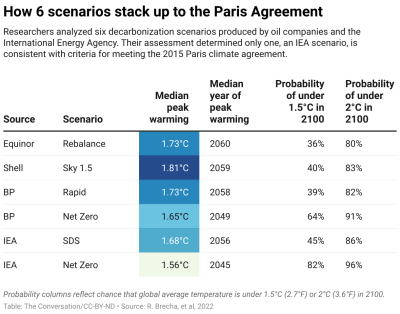

In a study published August 16, 2022, in Nature Communications, our international team analyzed four of these scenarios and two others by the International Energy Agency using a new method we developed for comparing such energy scenarios head-to-head. We determined that five of them – including frequently cited scenarios from BP, Shell and Equinor – were not consistent with the Paris goals.

What the Paris Agreement expects

The 2015 Paris Agreement, signed by nearly all countries, sets out a few criteria to meet its objectives.

One is to ensure the global average temperature increase stays well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 F) compared with pre-industrial era levels, and to pursue efforts to keep warming under 1.5°C (2.7 F). The agreement also states that global emissions should peak as soon as possible and reach at least net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century. Pathways that meet these objectives show that carbon dioxide emissions should fall even faster, reaching net zero by about 2050.

Scientific evidence shows that overshooting 1.5°C of warming, even temporarily, would have harmful consequences for the global climate. Those consequences are not necessarily reversible, and it’s unclear how well people, ecosystems and economies would be able to adapt.

How the scenarios perform

We have been working with the nonprofit science and policy research institute Climate Analytics to better understand the implications of the Paris Agreement for global and national decarbonization pathways – the paths countries can take to cut their greenhouse gas emissions. In particular, we have explored the roles that coal and natural gas can play as the world transitions away from fossil fuels.

When we analyzed the energy companies’ decarbonization scenarios, we found that BP’s, Shell’s and Equinor’s scenarios overshoot the 1.5°C limit of the Paris Agreement by a significant margin, with only BP’s having a greater than 50% chance of subsequently drawing temperatures down to 1.5°C by 2100.

These scenarios also showed higher near-term use of coal and long-term use of gas for electricity production than Paris-compatible scenarios, such as those assessed by the IPCC. Overall, the energy company scenarios also feature higher levels of carbon dioxide emissions than Paris-compatible scenarios.

Of the six scenarios, we determined that only the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 scenario sketches out an energy future that is compatible with the 1.5°C Paris Agreement goal.

We found this scenario has a greater than 33% chance of keeping warming from ever exceeding 1.5°C, a 50% chance of having temperatures 1.5°C warmer or less in 2100, and a nearly 90% chance of keeping warming always below 2°C. This is in line with the criteria we use to assess Paris Agreement consistency, and also in line with the approach taken in the IPCC’s Special Report on 1.5°C, which highlights pathways with no or limited overshoot to be 1.5°C compatible.

Getting the right picture of decarbonization

When any group publishes future energy scenarios, it’s useful to have a transparent way to make an apples-to-apples comparison and evaluate the temperature implications. Most of the corporate scenarios, with the exception of Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario, don’t extend beyond midcentury and focus on carbon dioxide without assessing other greenhouse gases.

Our method uses a transparent procedure to extend each pathway to 2100 and estimate emissions of other gases, which allows us to calculate the temperature outcomes of these scenarios using simple climate models.

Without a consistent basis for comparison, there is a risk that policymakers and businesses will have an inaccurate picture about the pathways available for decarbonizing economies.

Robert Brecha is a professor of sustainability at the University of Dayton and Gaurav Ganti is a PhD student in geography at Humboldt University of Berlin. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.