Japan-Korea forced labor deal fails to heal old wounds

On March 15, 2023, the South Korean government announced its plan to strike a “deal” with the Japanese government regarding forced labor during Japan’s colonial period (1910–1945).

Under the proposed arrangement, South Korean companies as the third party that benefited from Japanese economic cooperation in the past would provide compensation to the victims of forced labor.

As of May 7, 2023, 10 bereaved families of the laborers and one forced laborer have accepted the proposal. It is anticipated that this number will continue to rise.

The announcement stirred various responses, with some scholars criticizing the plan for leaving many questions unresolved. But both the South Korean and Japanese governments anticipate that this plan will improve bilateral relations and help resolve some diplomatic conflicts.

Still, the deal faces historical challenges from its inception, bolstering South Korean opposition.

The plan may reinforce Japanese politicians’ ongoing attempts to distort the history of Japan’s colonial rule over Korea. Prominent Japanese political leaders have consistently denied the Japanese Empire’s responsibility for war crimes and exploitation during the colonial period.

Despite offering official apologies as prime minister, Shinzo Abe refused to accept Japan’s accountability, arguing that the “definition of aggression” had not been established in 2013. Abe frequently contradicted his official statements through personal remarks, perpetuating the denial.

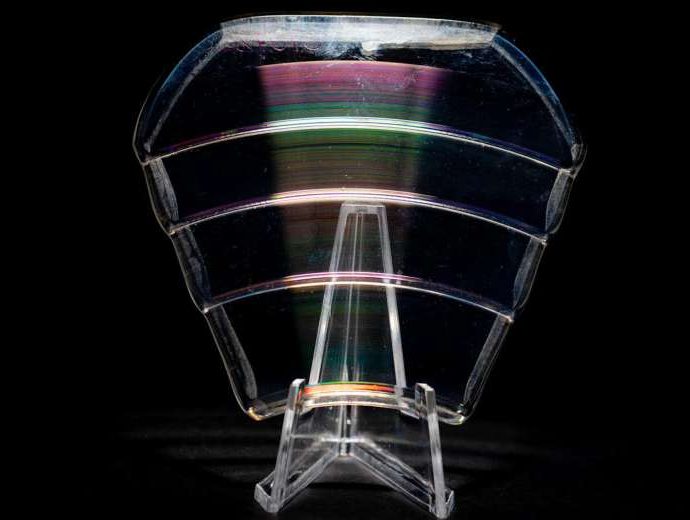

The Japanese government has also sought to glorify the past and conceal the dark history of Japan’s colonial rule. In 2015, the Japanese government succeeded in designating Hashima Island – also known as Battleship Island – as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The exhibit hall on Hashima Island primarily emphasizes its contribution to Japan’s modernization and rapid industrialization, neglecting the forced labor endured by approximately 60,000 conscripted Korean workers.

This stark contrast raises questions about the Japanese government’s commitment to addressing forced labor issues as stated in its UNESCO application.

Japanese politicians have attempted to sanitize the past by portraying Japanese wartime criminals as victims of war. Several Japanese prime ministers have visited or provided ritual offerings to the Yasukuni Shrine, which commemorates and enshrines war dead, including class-A war criminals from the Second World War.

Junichiro Koizumi visited the shrine annually as prime minister between 2001 and 2006 and Shinzo Abe visited in 2013. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has also sent a number of ritual offerings to the Yasukuni Shrine. These actions underscore how major Japanese politicians perceive Japan’s history during the colonial period.

The Japanese government has also emphasized the Japanese people’s victimhood during the war, particularly concerning the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States.

While former US president Barack Obama paid respects and laid a wreath at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in 2016 and G7 leaders visited it during the 2023 G7 Hiroshima Summit in 2023, no apologies were offered for the nuclear bombings.

But Japanese leaders have taken advantage of these visits to highlight the suffering of the Japanese people, without acknowledging the war crimes committed by the Japanese Empire.

Given Japanese leaders’ denial of the Japanese Empire’s atrocities, as opposed to the German government’s approach towards the Holocaust, South Koreans will likely oppose the forced labor deal.

The decision to pursue the deal has faced backlash from South Korean NGOs and progressive groups who find it humiliating. A public poll on the forced labor deal reveals that 60% of South Koreans oppose it.

Despite the low approval rate, neither the South Korean government nor the ruling People Power Party has conducted a public hearing to address public concerns. Instead, the opposition Democratic Party held a public hearing on March 23, 2023 focusing on compensating the victims of forced laborers and comfort women — also known as sexual slaves.

On the forced labor issue, the South Korean Supreme Court issued a ruling in 2018 that officially recognized human rights abuses committed by certain Japanese companies against South Koreans and ordered the firms to pay compensation.

But these companies – including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Nippon Steel – have not yet complied with the court’s order. The Japanese government is believed to have obstructed these companies from adhering to the court ruling. The proposed deal could exacerbate the situation by further absolving the companies of their responsibility.

Considering the significant impact of diplomacy and new relations with Japan on South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s low approval rating, he treads on delicate ground. Enforcing the deal without the consent of the South Korean people will render it ineffective.

If this happens, it will meet the same fate as the failed 2015 comfort women deal between the South Korean and Japanese governments, which also faced public resentment in South Korea.

Jinsung Kim is a PhD candidate in the Department of Asian Studies and a Centre for Korean Research Fellow at the Institute of Asian Research, University of British Columbia.

This article was originally published by East Asia Forum and is republished under a Creative Commons license.