It’s been three decades but Uma Krishnaiah clearly remembers the last conversation she had with her husband, just hours before his murder.

It was 5 December 1994 and the couple had woken up early as G Krishnaiah, a top civil servant in the northern Indian state of Bihar, had to leave home at 5am to travel to an important meeting in Hajipur, a town more than 130km (81 miles) away.

“It was a freezing cold morning but he was walking on the lawns. I asked him to come inside because I was worried he would catch a cold,” she told me.

“But he told me not to worry. He said there are so many poor people who don’t even have warm clothes. I’m wearing a sweater, I’m dressed warmly, nothing will happen to me.”

Hours later, Mrs Krishnaiah was standing in a hospital, looking at her husband’s bloodied body. “He had so many injuries on his face and body,” she said, her voice breaking with emotion.

Krishnaiah – whom journalists and former colleagues remember as “an honest and upright officer” and “a good administrator” – was returning from the meeting when his car was stopped by a mob protesting against the killing a day earlier of Chhotan Shukla, a dreaded gangster-turned-politician.

The mob, comprising thousands of Shukla’s supporters, pelted the officer’s car with stones, dragged him out and started beating him.

“Krishnaiah, who was the district magistrate for Gopalganj, kept trying to tell the mob that he had nothing to do with the Shukla murder, which took place in an adjoining district,” says Amarnath Tiwari, senior journalist in the state capital, Patna.

“But the crowd lynched him and one man shot him in the head. Police later retrieved his bloodied body from the scene of the crime.”

The murder turned Mrs Krishnaiah’s life upside down. The brazenness of the crime and the brutality with her husband was murdered also sent shockwaves through the country and made national headlines.

Three decades later, the gruesome crime is back in the news after Anand Mohan Singh, who had been serving a life sentence for the civil servant’s murder, walked out of prison this week.

Singh, then a legislator in the state assembly, was charged in the murder case with inciting the crowd to attack and shoot the official.

In 2007, a local court convicted him and gave him the death penalty. A year later, the Patna high court converted it into a life sentence, which was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2012.

Until recently, Singh couldn’t be freed because according to Bihar’s jail manual, “those convicted for murdering a public servant on duty” were not entitled to early release.

But earlier this month, the state government, led by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, dropped the clause from the manual and announced the release of 27 prisoners, including Singh.

The decision has been criticised by some opposition politicians, activists and citizens, with many comparing Singh’s release with last August’s decision by the Gujarat government to set free convicts in the notorious gangrape of a Muslim woman and murder of her family during deadly 2002 religious riots. Gujarat officials said a state government panel had approved their release because the men had spent more than 14 years in jail and because of other factors such as their age.

The association of civil servants has asked the Bihar government to reconsider its decision.

“Such dilution leads to impunity, erosion of morale of public servants, undermines public order and makes a mockery of administration of justice,” it said in a statement on Twitter.

But the Bihar state government and Singh have defended the move, saying it isn’t illegal. “He has served his sentence and is being released legally,” Bihar’s Deputy Chief Minister Tejashwi Yadav told reporters.

However, Mr Tiwari says the decision is rooted in politics.

“Singh commands influence among the upper-caste Rajput community which makes up 4% of the state’s population. And the state’s governing alliance, led by Mr Kumar and Mr Yadav, wants his support in next year’s general elections,” he told the BBC.

But away from the political ping pong, the decision has been greeted with dismay by the Krishnaiah family, for whom it has reopened old wounds.

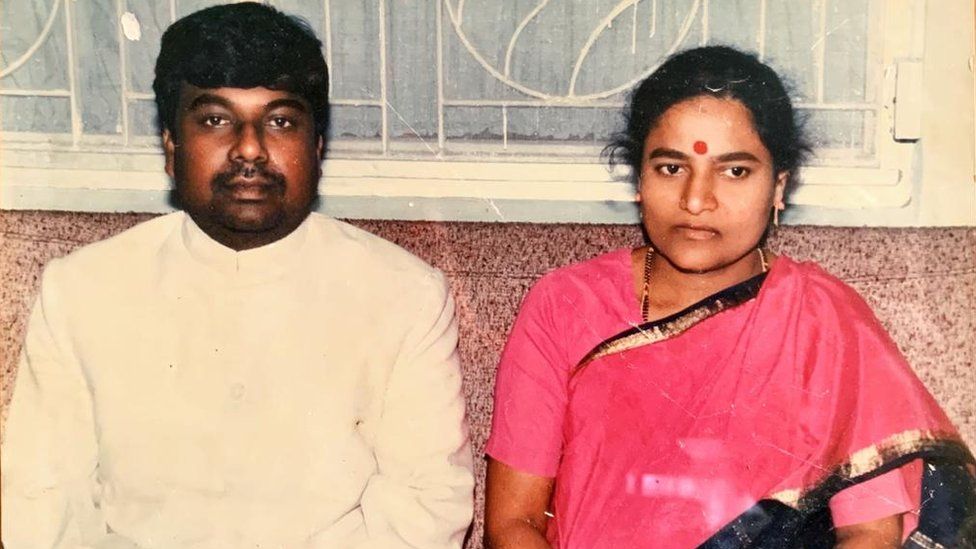

Mrs Krishnaiah told me she had met her husband, who was from a poor Dalit (formerly untouchable) family, at college in the southern city of Hyderabad in 1981. They fell in love and married five years later. At the time of his murder, they were raising two daughters who were four and five-and-a-half.

A day after his death, she moved back with her children to Hyderabad where she took up a job as a college teacher to support the family.

Singh’s conviction and sentencing had brought her some solace, but to see him walk out of prison has left her heartbroken and distraught.

“My husband was a government officer. He was killed while working. How can they set free his murderer? The government should reconsider the decision,” she said.

“This will send wrong signals to the society and encourage criminals. They will now think that even if they commit a heinous murder, they will go free.”

Mrs Krishnaiah said she had appealed to the prime minister and the president, seeking their intervention to send her husband’s murderer back to prison.

On Thursday morning, hours after Singh walked out of prison, her daughter Padma told news agency ANI that the family was “disheartened”.

“I request Chief Minister Nitish Kumar to give a second thought. His government has set a wrong example. It is unfair not just to a family but to the whole nation,” she said, adding that they would appeal against the decision in court.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: