Last week, hundreds of supporters of controversial self-styled preacher Amritpal Singh stormed a police station in the northern Indian state of Punjab, demanding the release of an arrested aide.

The mob of angry young men – many holding guns and swords – broke down barricades and only left the scene after getting an assurance that the aide would be released. Police officials later claimed that they had been unable to stop the crowd as they were carrying a copy of the Guru Granth Sahib – the holy book venerated by Sikhs – as a shield.

The events propelled Singh – who is around 30 years old and says he supports the Khalistan movement for a separate Sikh homeland – to national attention.

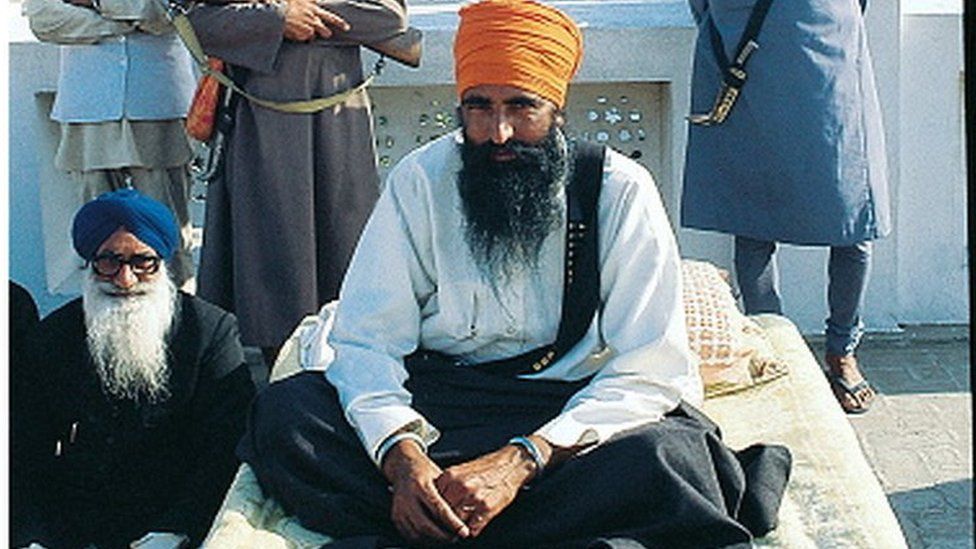

What also raised eyebrows was Singh’s appearance, which resembled that of the man he claims to draw inspiration from: Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a preacher accused by the Indian government of leading an armed insurgency for a separate Sikh homeland in the 1980s. He was killed in the Indian army’s controversial Operation Blue Star in 1984.

During the insurgency, which lasted about a decade, thousands of people lost their lives. These included prominent leaders and ordinary people targeted by insurgents, while many young Sikhs were killed in police operations – some of which were ruled to be staged by Indian courts. Punjab still bears the scars of that violence.

“What we are seeing in Punjab definitely forces you to think whether we are headed back to the dark era of militancy,” says Shashi Kant, a former director general of police in Punjab. “The atmosphere of fear is real.”

But some argue that Singh’s popularity has been blown out of proportion.

“Even though the sentiment of separatism never died down completely, it did lose popular support in the 1990s. Not everyone in the state supports people like Amritpal Singh and their demand for a violent movement. It is still a very small chunk of the population,” says Prof Parminder Singh, who teaches at the Guru Nanak Dev University in the state.

Punjab chief minister Bhagwant Mann has also said that “everyone lives in harmony” in the state and that there is a “special bond” between communities despite attempts to destroy it.

“A thousand people [supporters of Singh] don’t represent Punjab,” he said.

Who is Amritpal Singh?

Not much is known about Singh’s early years. A resident of Jallupur Khera in Punjab’s Amritsar district, he moved to Dubai in 2012 to join his family’s transport business.

His LinkedIn profile says he has a mechanical engineering degree from a university in Punjab and that he worked as an “operational manager” at a cargo company.

For many years, reports say, his popularity was restricted to social media where his views on Sikh unity and statehood found plenty of resonance.

In August last year, he travelled to India from Dubai, looking visibly different from old photos in which his hair and beard were neatly trimmed.

Now, he looked like a devout, practising Sikh – with unshorn hair tucked into a blue turban, a long, flowy beard, a steel bangle on his wrist and a small sacred dagger, called kirpan, hanging from his waist.

A month later, Singh was appointed head of Waris Punjab De (Heirs of Punjab), an organisation formed by Deep Sidhu, an actor and activist who was arrested in connection with violence during a protest held by farmers – he died in a car accident last year..

The ceremony, which was attended by thousands of people, was held in Rode, the ancestral village of Bhindranwale.

Why is he popular?

Singh’s supporters often compare him with Bhindranwale, whom he calls an “inspiration”.

In his speeches, Singh emulates Bhindranwale and his hardline views – openly calling for a separate state for Sikhs, claiming it to be the only “permanent solution” to Punjab’s problems, from water disputes to drug addiction to the erosion of Punjabi culture.

Singh, however, personally dismisses the comparison: “I am not even equal to dust of his feet. I only walk the path shown by him,” he told The Indian Express newspaper last year.

Prof Ashutosh, a political scientist teaching at the state’s Panjab University, says he finds Singh’s sudden rise to prominence “mysterious”, given his age.

But he adds that Singh has been able to play on Sikh anxieties by drawing parallels between the idea of their sovereignty and the Hindu nationalist identity.

Punjab, known as India’s bread basket, is still a relatively well-off state. But experts say a persistent unemployment problem and farming crisis have shrunk the state’s social and economic standing.

“With the governing Bharatiya Janata Party’s supporters clamouring for a Hindu nation, some Sikhs feel the need for a leader who talks about the injustices done to them and could represent their interests and problems,” Prof Ashutosh says.

Prof Khalid Mohammad, also from Panjab University, says that social media has played a significant role in Singh’s popularity as it allowed him to “connect with the masses easily”.

In November, Singh led a month-long religious procession across the state to encourage Sikhs to become baptised (go through the Amrit ceremony), forgo drug consumption – a serious problem in Punjab – and ditch customs such as dowry and caste-based discrimination.

A month later, his followers also made headlines for destroying furniture at a gurudwara after Singh said that people should only be seated on the floor in the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib.

Prof Parminder Singh says that Singh’s popularity surge can also be attributed to the frustrations of many young people in Punjab.

“There are a number of young people in Punjab who are not well-to-do, not that educated, can’t find any work and don’t have the resources to go abroad. Many of them may have moved towards this kind of religious fundamentalism,” he says.

Why is his rise a concern?

In his speeches, Singh often argues that the demand for Khalistan is absolutely justified. He also seems to hold a considerable appeal for his followers.

More than anything, though, his sudden rise and popularity serve as a chilling reminder of the state’s violent history .

Today, decades after the bloodshed, Punjab has mostly reverted to normalcy, its cities alive again with the hustle bustle of daily life.

Now, some worry that the state may see turbulent times again.

A former senior Punjab police officer who joined the force in the 1980s told the BBC that he had seen many attacks on police stations in the past. “But this is the first time that the police have been seen so helpless,” he says.

Prof Parminder Singh also points out that Singh was travelling in Punjab carrying swords and guns for the past few months without a case being filed against him.

“Overall, this trend is dangerous and should not be allowed to develop. Else Punjab would enter a serious phase of crisis.”

Read more India stories from the BBC:

-

-

6 June 2014

-

-

-

19 November 2021

-