Throughout Phnom Penh, history sits layered in stacks and along shelves, where hundreds of thousands of documents carry the gritty historical details of the Khmer Rouge state and its victims’ outcry.

Many of these are among the files of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), also known as the Khmer Rouge tribunal. The chambers are a joint effort between the domestic court system and the UN that was tasked with investigating and prosecuting surviving leaders of the regime for decisions that led to the deaths of upwards of 1.5 million Cambodians from 1975-1979.

The trial portion of this started in 2007 and ended last September. This has ushered in the final act of the ECCC: a three-year “residual phase” tasked with archiving the tribunal’s massive trove of evidence while delivering services to the many regime survivors who participated in the court’s proceedings.

Those now working to preserve evidence at the ECCC and elsewhere say the process is essential to maintain the testimony of the survivors as a critical learning tool for younger generations to more fully understand the failures and atrocities of the Khmer Rouge. At the same time, privacy concerns and other questions remain about how much evidence can be made safely available to the public. Given the wide scale of the regime’s atrocities, many survivors are still alive, with some living in close proximity to accused perpetrators.

“The circumstances in Cambodia are very unique,” said Milan Jovancevic, a programme management officer for UN Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials (UNAKRT). “Many people were victims, there are many perpetrators across the country, so putting the document to the public may actually risk human life.”

For that reason, some documents within the ECCC’s archive of public history will still be red-marked as classified. This has always been up to judges, who review content for sensitivity to see if it can be published without risking danger to victims, Jovancevic explained.

The ECCC already maintains a public database available upon request. This will be updated for completely open access through a new website and database by the end of the year.

“This is, to my knowledge, the first time that any international tribunal has ever done that,” Jovancevic said.

“Nothing should be confidential”

At the same time, the ECCC is not the only group creating a comprehensive archive of evidence. Multiple organisations are updating and managing their own Khmer Rouge databases.

“We wanted the whole world to have one archive at home,” said Youk Chhang, executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). “For us, archiving these is the beginning of the healing process.”

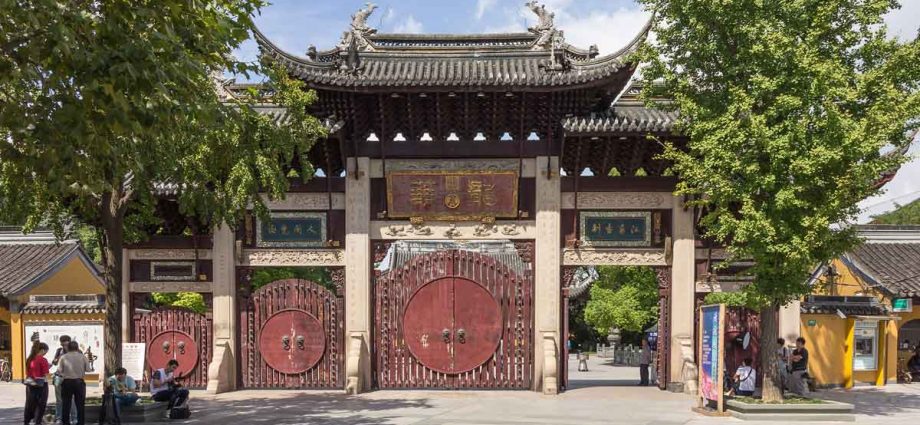

On a recent afternoon in a corner of a library lined with packed shelves in DC-Cam’s headquarters, an archivist opened boxes of documents to prepare for their work. The team there preserves court documents in different formats such as microfilm, photocopy and now the latest updated digital scans.

As an organisation, DC-Cam is already devoted to preserving memories of the Khmer Rouge era. Youk himself is a survivor and a prominent advocate for others affected by the regime.

He maintains that evidence used in the tribunal should be made as publicly available as possible. At the court’s request, DC-Cam had gathered and provided about half-a-million documents to the prosecution.

According to Youk, those documents are sorted into five categories: paper documents; photographs; films; physical evidence such as maps of prisons and massacre sites; and interviews with both former Khmer Rouge officials and survivors.

Youk said many of these documents are considered only circumstantial evidence and need to be combined to decisively show what happened.

Some in the residual phase have argued that evidence may need to remain classified for the public good or to safeguard the privacy of individuals.

Youk mostly rejects that logic.

“Khmer Rouge history is a public history,’’ he said. “I recommend keeping it at the National Archives of Cambodia. Nothing should be confidential in Khmer Rouge history.”

Cleaning up after the trials

By the end of its trial portion last year, the ECCC had indicted 10 Khmer Rouge leaders in four mega-cases. However, due to procedural disagreements and the advanced age and poor health of the defendants, the court only convicted three.

Jovancevic said parts of Cases 001 and 002 have been largely classified.

Case 001 was the very first before the court and centred on defendant Kaing Guek Eav, also known as “Duch”. As the former chairman of the notorious Khmer Rouge S-21 Security Center in Phnom Penh, Duch’s case ended in a high-profile win for the tribunal in 2010 when the court convicted him of acts of genocide and other crimes against humanity.

After first handing him a 35-year prison term, which Duch appealed, the court passed down a life sentence. He died in 2020.

Case 002 was the largest on the ECCC’s roster and included the bulk of the most serious crimes of the Khmer Rouge. Its defendants were some of the highest-ranking party members: Khieu Samphan, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith. Respectively, they had served the regime as its head of state; general secretary; and ministers of foreign and social affairs.

Cases 003 and 004 implicated Khmer Rouge military leaders and particularly brutal cadres who had carried out purges under military chief Ta Mok, who died in 2006. Documents related to these cases, which became mired in procedural issues, are mostly unclassified.

Tola Peang, an archivist officer at the ECCC, explained there are currently about 110,000 documents simultaneously undergoing uploading and reclassification.

The tribunal’s soon-to-be-updated database will include new functions such as optical character recognition for Khmer documents that allow for text searches and artificial intelligence capable of reading and linking concepts such as names and locations.

“[The ECCC is] the only tribunal among all the international ones that has consistently digitised all of its documents since day one,” Jovancevic said. “Every single document that is put by the judges or issued by the judges is under a digital database.”

Multiple databases, not enough understanding

In the coming years, such databases will only grow more complete as the various archiving organisations continue their work.

A 2019 survey published by DC-Cam, revealed different attitudes amongst members of the public, academics and former Khmer Rouge cadres in Cambodia over the management of its own archive. But overall the respondents agreed these legal assets “must be stored and preserved at an institution which is credible and trusted by Cambodian people, is independent and neutral, and offers easy access.”

Other database projects include the Tuol Sleng archive in the museum established at the S-21 facility and online tools such as the e-learning platform maintained by the organisation Legal Aid of Cambodia. These groups are already working to present the country’s history to younger generations.

However, Boravin Tan, a researcher and lecturer at the Royal University of Law and Economics in Phnom Penh, said these archives aren’t very well-known to the general public. And for the ECCC archive, Boravin said the complexity of the legal arguments and factual evidence used in the tribunal is a key challenge for legal professionals looking for insights.

She believes the ECCC archives could be an educational treasure trove if they were more accessible and their value to legal and historical study was more widely understood.

“The most ideal initiative would be to institutionalise this [course] as part of the curriculum for legal education to make it an asset of the law school,’’ she said.

Boravin works within the university’s Center for the Study of Humanitarian Law. She said the documents provide a factual background for a historical narrative that is often subjective.

“A completely 100% accurate record of history is not possible, but at least it [provides] a principal aspect of narrative or at least [is] trying to be a little bit more comprehensive and more critical,” she said of the archive.

As the tribunal’s residual phase continues, Youk hopes younger generations and those to come will revisit and write about the Khmer Rouge as an integral and formative part of their national history. He believes these stories need to be known for the healing process to continue.

For Boravin, digital archives such as the ECCC provide a bridge between these generations.

“[It is] a recognition, remembrance as well as reconciliation for the present and future of Cambodia,” she said.