As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine complicates European energy security, many countries are being forced to scramble for new sources of oil and gas. For Germany, which imported 34% of its oil and 55% of its gas from Russia before the war, diversification has become existential.

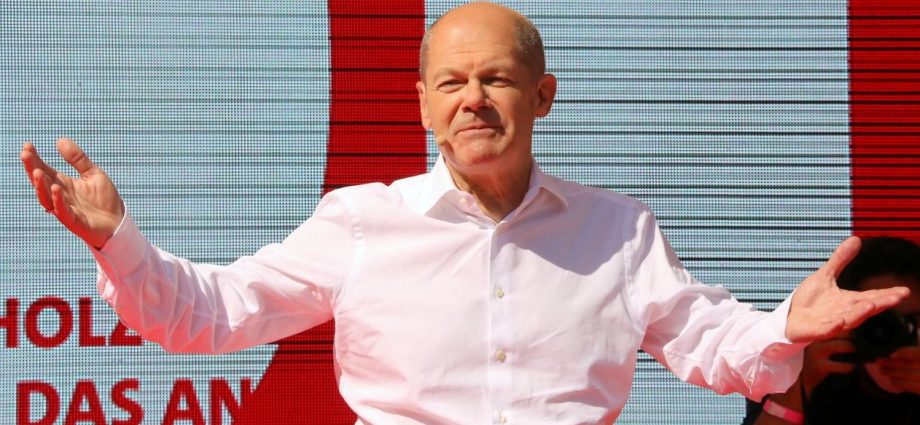

Topping the list of potential suppliers are nations of the Arab Gulf region. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz recently visited Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar to secure gas deals and stabilize skyrocketing prices.

With those visits now in the rearview mirror, many are wondering what was accomplished beyond a few energy contracts. Did Scholz’ tour signal a deepening of German-Gulf relations?

While German-Gulf ties aren’t new – Germany has traded with Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states for decades – Germany is now engaging with the region from a position of vulnerability. The more that German energy security gets entangled with the Gulf’s energy markets, the more invested Berlin will become in the region’s stability, including its maritime security.

It remains to be seen what comes of Scholz’ visit, particularly given that the contracts are modest compared with what Germany lost with Russia (in recent years, Germany has been by far the biggest European Union buyer of Russian fossil fuels).

In Qatar, for instance, no deal on liquified natural gas (LNG) was concluded because of differences over the duration of contracts that would contradict Germany’s target of becoming carbon-neutral by 2045. A contract signed in the UAE, meanwhile, secured just 137,000 cubic meters of LNG, a fraction of the 56.3 billion cubic meters Germany received from Russia in 2020.

But no matter what the visit yields, there’s little question Russia’s war in Ukraine has accelerated a trend that was already under way.

As a globalized market economy that is heavily export-oriented, Germany has always prioritized the free flow of goods, stable oil and gas prices, and the safe passage of fossil fuels. By becoming a direct importer of Gulf energy supplies, German interest in the region’s security will only grow.

The Arab region, including the Gulf, will also be essential if Germany is to meet its green energy targets. Carbon neutrality will be impossible without the import of large quantities of green hydrogen, which Arab countries in the Gulf region are planning to produce in abundance.

Germany had already concluded hydrogen agreements with several countries, including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, before Scholz’ trip, and that energy source was a key issue during his visit.

While Germany – and the rest of Europe, for that matter – is increasingly reliant on the Gulf region for energy, this will not necessarily translate into major shifts in Germany’s security policy vis-à-vis the Gulf.

The “historic turning point” – or Zeitenwende – that Scholz spoke of in February after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine didn’t mean that Berlin would strike a more militarized security policy in its bilateral relations. Rather, only that Germany would dramatically increase its defense spending to modernize its armed forces.

German opposition figures want Scholz to go further and have called for security cooperation and arms sales to the Gulf monarchies, the rationale being that it would give Germany more bargaining power and status in the region, akin to that enjoyed by other European heavyweights such as the United Kingdom and France.

But such a policy shift will not occur under the current government, and rightly so. No matter how many weapons Germany sold it would never obtain substantial influence on national or regional politics given the Gulf’s financial resources, its decade-long emancipation from the West, and its profitable navigation of the multipolar world order.

Germany has reason for restraint. There are often large discrepancies between Germany and some of the stances from Gulf countries on regional conflicts like Yemen, Libya, Syria and Iran. Given these differences, diplomacy and dialogue will continue to top Germany’s policy approach when tackling security challenges in the region and, as before, it will operate within Western multilateral settings.

While arms sales and military cooperation are off the table, Germany and its Gulf allies will continue to focus on issues such as energy security, climate mitigation, and bilateral trade and investment. There will likely be more coordination and joint action in humanitarian assistance and development aid, and more cultural and societal exchanges.

Each of these areas are aligned with the EU’s strategic partnership for engagement and cooperation with the Gulf monarchies.

One aspect of German foreign policy that has changed is a softening of critique over human-rights issues in the region. The existential nature of the current energy crisis subordinates all policy areas where the two sides do not converge.

Germany has long pursued realpolitik in the region, and Scholz is betting that criticism for putting the economy over human-rights concerns will wane and pragmatism will prevail. Odds are he’s right. With mounting hardships fueled by high inflation, soaring energy prices, and the looming possibility of a shortage of basic goods, there’s a good chance that the government’s view will find its way to society as well.

Germany has been badly burned by an energy policy that made it too reliant on Russian gas, and the Ukraine war has led to a rethink on long-standing defense and economic policies.

And, as Europe’s largest economy, which for decades walked the path of dialogue and financial prudence, Germany’s fresh approach to the Gulf region will be watched closely by other EU countries as the continent looks to navigate through what many believe is the greatest crisis since World War II.

This article was provided by Syndication Bureau, which holds copyright.