JAKARTA – Former Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) commander Andika Perkasa’s brave hearts-and-minds campaign in Papua’s rebellious Central Highlands appears doomed to failure, underscored by the abduction last week of a New Zealand pilot and the torching of his plane on a remote jungle airstrip.

Confronted by well-armed rebel bands whose fight for independence has morphed into outright criminality and the bloody pillaging of villages, governance in some of the eight regencies in the newly divided province has broken down.

The kidnapping of Phillip Mehrtens, a pilot for frontier airline Susi Air, has raised fears the rebels may now be threatening air operations that often provide the only lifeline to small towns and villages across swathes of the largely roadless region.

Light aircraft belonging to Susi Air, Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF), which serves far-flung religious missions, and about eight other small carriers are increasingly taking random groundfire now that automatic weapons have replaced bows and arrows in rebel hands.

The entire territory of Papua has 283 airports, most of them dirt airstrips like Paro in Nduga regency, where gunmen stormed Mehrtens’ Pilatus Porter PC6 after it landed on February 8 carrying five Papuan passengers and 450 kilograms of cargo.

The passengers were released unharmed, and 15 workers building a nearby health clinic were quickly evacuated, but the pilot was taken hostage and the plane was burned, a similar fate to that of a MAF plane two years ago in Intan Jaya.

Susi Air is owned by former fisheries minister Susi Pudjiastuti, who bought her first two nine-seat Cessna Caravans to fly fresh fish and lobster from the south coast of Java to Jakarta, then slowly built up her fleet after the planes were hired by aid agencies to help in the 2004 tsunami relief effort.

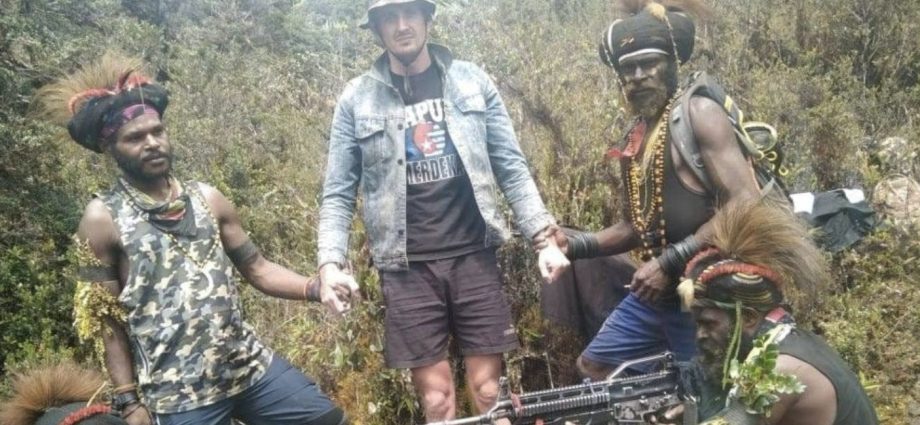

The rebels are part of the West Papua Liberation Army (TPNPB), the military wing of the long-established Free Papua Movement (OPM), which the government now refers to as an Armed Criminal Group (KKB) to erase the political motive for many of its brutal actions.

Despite what may be seen as government propaganda, independent sources in the Central Highlands say the KKB acronym is, in fact, a description more suited to what has been going on in recent years since the independence struggle took a different turn.

Analysts point to the history of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which in the post-peace era became increasingly associated with organized crime. The OPM may be headed the same way as young indigenous Papuans, in coastal areas at least, look to a better future through economic growth.

Seeking to make his mark in his one year in charge, Perkasa ended offensive operations in early 2022, telling a parliamentary commission that he wanted to abandon the combat-heavy policy in Papua and replace it with a softer “humanistic” approach.

Publicly endorsed by Vice President Ma’ruf Amin, who nominally oversees Papua policies, and newly installed army chief of staff General Dudung Abdurachman, the move foresaw servicemen functioning as teachers, health workers and building contractors.

But while the change was welcomed, the timing has been unfortunate. The level of violence against civilians, much of which goes unreported, has increased significantly across the highlands over the past few years, according to residents.

Data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project also shows attacks on police and military forces by emboldened, better-armed adversaries rose from 34 in 2019 to 137 in 2021 and then dropped to 98 last year as the army reduced its presence.

Most of the arms and ammunition have been seized in raids on isolated outposts, but the rebels are also cashed up because of worrying leakages from the government’s Special Autonomy Fund and the fruits of rampant illegal gold mining.

Apart from the direct transfer scheme, the government also provides 1 billion rupiah (US$656,000) a year to village heads to pay for transportation – money that has become a magnet for the rebels. “As one researcher put it: The highlands have become very fertile ground for extortion.”

Officials describe as “non-official” rebel statements saying that Mehrtens will only be released if President Joko Widodo agrees to negotiate the future of Papua and the New Zealand government talks directly to the rebels, neither of which is likely to happen.

TPNPB spokesman Sebby Sambom said Mehrtens is being treated humanely at a location about two days walk into the jungled mountains from the little-used airfield, where security was effectively non-existent.

He said Mehrtens was “not our enemy” and was being treated “like family,” but in the next breath, he alleged that New Zealand as well as Australia, the United States and China had allowed Indonesia to kill Papuans for the past 60 years.

After dispatching paramilitary police from a nearby peace-making task force to seek Mehrtens’ release, Abdurachman apparently decided they weren’t up to the task and deployed an elite special forces (Kopassus) unit from Jakarta instead.

In a series of videos released on February 15 showing Mehrtens surrounded by gun-toting fighters, the kidnappers warned the pilot “will die here … like us” if the military makes any attempt to rescue him.

Political coordinating minister Mahfud MD says the government has been making every effort to secure Mehrtens’ freedom, but making it clear it would prioritize a “persuasive approach.”

The abduction was the work of 24-year-old Egianus Kogoya, whose father, Daniel Yudas Kagoya, was among eight rebels killed by troops during a mission to rescue 11 foreign and Indonesian botanists abducted in nearby Mapenduma in May 1996.

Two of the hostages also died in the assault, which was directed by then-special forces commander Prabowo Subianto, the current defense minister, who quietly brought in Israeli drone operators to track the kidnappers.

According to one well-placed source, the latest abduction was triggered by the Nduga administration’s failure to make a Christmas-New Year payment to Kogoyo, a practice of pay-offs that has become commonplace across the highlands.

Nduga is now part of Highland Papua, one of three provinces created from the division last year of the old Papua province, a vast area of more than 317,000 square kilometers, ostensibly to help improve governance and economic growth.

The neighboring mountainous regencies of Intan Jaya, Puncak and Puncak Jaya belong to Central Papua, extending from northern Nabire to Mimika on the south coast, which includes Timika and mining giant Freeport Indonesia’s tightly guarded Grasberg mine.

Over the past two years, Kogoyo and his brother, Undinus, have built a reputation for ruthlessness, much of it against their own people. Calling many of the rebels “thugs,” one resident told the Asia Times: “You have to pay them off, otherwise nothing will function.”

Undinus, who moved into Intan Jaya last year, was involved in an unreported incident on January 26 in which 200 fighters, 30 armed with assault rifles, surrounded a religious mission in Pogapa and threatened the occupants of nearby villages.

Witnesses say a tense situation was finally defused after acting Intan Jaya regent Apolos Bagau, a former education official and member of the regency’s dominant Moni tribe, flew in with a 50 million rupiah pay-off.

Bagau was given the job last December in place of the retiring Natalis Tabuni, 45, an ethnic Dani tribesman and close associate of former Governor Lukas Enembe who had served two terms through what were widely seen as rigged elections.

Faced with a wave of violence two years ago, Tubani and his staff abandoned the regency capital of Sugapa (population: 9,500) and re-established their office 180 kilometers away in Nabire, a city of 100,000 people on the north coast.

Bagau reportedly followed suit in mid-January, about the same time as a company of troops ended their three-year deployment in the area and days after governor Enembe was arrested in the Papua provincial capital of Jayapura on charges of corruption.

Only last week, acting Papua provincial secretary Doren Wakerkwa called on Bagau to return and take responsibility for the deteriorating security situation in Intan Jaya, which has brought with it the collapse of a functioning administration.

In the meantime, residents complain that roving rebel bands rape and pillage at will across a region where the only security has been provided by about 1,000 Police Mobile Brigade (Brimob) paramilitary troopers and three battalions of ill-trained territorial soldiers since late 2021.

An East Java-based Army Strategic Reserve (Kostrad) battalion has only recently been sent to Nduga, but it is unclear whether the military has resumed the practice of rotating thousands of non-organic territorial soldiers to Papua.

Coastal Timika, a city of 143,000 and Freeport’s lowland logistics base, is the home of the still non-operational 20th Brigade, part of a newly raised third Kostrad division.

Based in Makassar, South Sulawesi, the 3rd Division will ultimately be responsible for eastern Indonesia covering the main island groups of Sulawesi, Maluku, Papua and East and West Nusa Tenggara.

Military experts warned last year that Perkasa’s efforts to prioritize civic action missions, which are normally planned after combat operations have been concluded, would be difficult in the existing environment.

ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute researcher Made Supriatma says the existing territorial structure is already woefully inadequate to tackle the task despite a move to recruit 3,000 indigenous Papuan youths into the army and police.

Security has continued to decline in the highlands, marked In March 2022 by the murder of eight phone workers near Beoga, the same village in Puncak regency where a year earlier gunmen killed the only Indonesian general to die from hostile fire.

It was the worst attack on civilians since December 2019 when TPNPB fighters massacred 19 bridge workers on the Trans-Papua Highway in Nduga, a project that will open road access to the entire length of the Central Highlands for the first time.

Two months earlier, during a riot sparked by a case of discrimination in far-off Surabaya, rebels penetrated Wamena, the new capital of Highland Papua, setting government buildings ablaze and killing at least 33 non-Papuan civilians.

With Perkasa gone and looking for a future in politics, it may not be long before the government decides his well-meaning program should go with him and bring in more military reinforcements to restore order – with all the dangers that entails.