Despite a lifetime of struggle, Rohingya rights activist Aung Kyaw Moe believes there’s a solution to every problem, even when things are beyond his control.

In June, his persistence led to a landmark moment with his ascension from an advisory role to become the deputy human rights minister to the National Unity Government (NUG). His appointment within the exiled civilian administration – which operates in parallel to the military junta that ousted democratically elected leaders in the 2021 coup – marks the first time a Rohingya representative has held a ministerial position in any Myanmar government.

“I believe that regardless of the challenges, you have all the capacity to be a victor,” he said. “It’s all a matter of how you transform yourself from a victim to a victor.”

Aung Kyaw Moe has advocated for the rights of the stateless Muslim minority group for more than a decade. He has more than 15 years of experience working in U.N. agencies and non-governmental organisations in Southeast Asia, Afghanistan and Liberia and won several human rights awards, including the prestigious E.U. Schuman Award in 2019.

But although he now has a say in the shadow government’s decisions, the establishment of Rohingya rights in Myanmar is far from straightforward. The embattled NUG still lacks control over territory in Myanmar and faces an authoritarian military that denies the Rohingya citizenship and basic rights.

In 2017, the Myanmar military conducted a brutal crackdown on the predominantly Muslim majority, pushing more than 700,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh. Today, about a million Rohingya refugees remain there, living in squalid camps with uncertain futures just over the border from their native Rakhine State in western Myanmar.

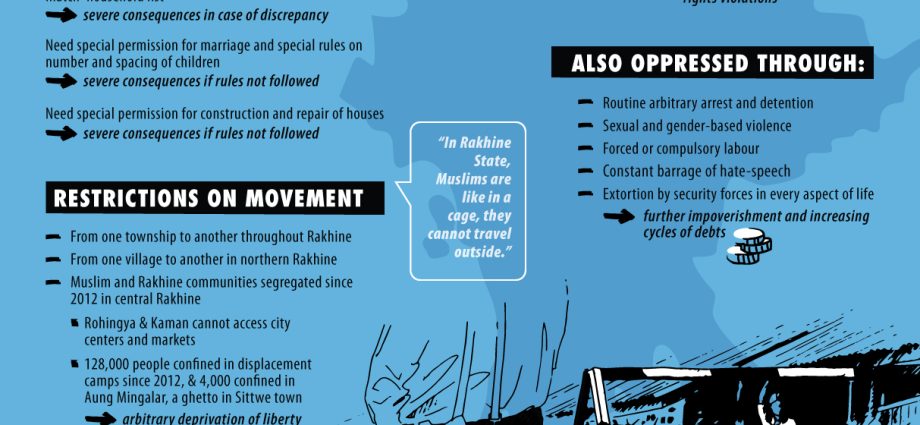

The persecution of the Rohingya minority is deeper-rooted still, dating back to warfare and displacement in the late 1700s. Later on, post-colonial religious segregation and discrimination caused this population to be considered illegal immigrants in their own country. The government of Myanmar officially categorised them as “Bengali” in 1982, stripping them of citizenship rights and forcing them to live without basic human rights ever since.

Born in Rakhine State in 1973, Aung Kyaw Moe witnessed decades of oppression and violence against the Rohingya people. He began activism as a student when the discriminatory policies against his ethnic group felt increasingly unfair.

“At that time, Rakhine State was an open prison with strict movement restrictions for people like us,” Aung Kyaw Mow said of his youth. “The inspiration [to work in human rights] came from the hardship and trauma.”

Despite growing up with limited educational opportunities due to his Rohingya identity and religious minority status, Aung Kyaw Moe managed to complete his bachelor’s degree in Yangon. But further education seemed to not be an option for him in Myanmar.

“[As a Rohingya] there is a double layer of discrimination to overcome in order to truly become who you want to be and influence others,” he said. “I then began to look for alternative ways to achieve my goals.”

He went on to graduate with a master’s degree from Deakin University in Australia. He later participated in leadership programmes through the United States Institute of Peace and the Dalai Lama Fellowship.

Facing threats to his safety due to the nature of his advocacy for the Rohingya, Aung Kyaw Moe also fled Myanmar multiple times and separated from family members as early as 1992, with some of them staying in Rakhine, others fleeing to Yangon or neighbouring Bangladesh. Despite the difficulties, he continued activism while being in and out of the country, testifying about atrocities before the U.N. Human Rights Council and International Criminal Court.

“It’s hardly acceptable for me. … We could have saved him from being killed.”

Aung Kyaw Moe, speaking of his elder brother

But his choices also forced him to take a strong stand about cutting ties. Aung Kyaw Moe hasn’t been in touch with his close family members for years to ensure their anonymity and safety from persecution.

That may not have been enough. Unknown assailants murdered his older brother Than Myint in June near a Yangon mosque. Aung Kyaw Moe believes the killers are likely affiliated with extremist groups linked to the military government.

“He was just a simple person who was making his life through a small pharmacy that he ran,” he said of his brother.

Though Than Myint had insisted that his younger brother not worry for his safety, Aung Kyaw Moe said he’d always been concerned about him.

“It’s hardly acceptable for me because there were things I could do to push him to relocate to a different country, at least to Thailand,” he said. “We could have saved him from being killed.”

But his brother was not his only loss. Aung Kyaw Moe also lost his father in 2012. His father had been arrested and, shortly after his release, suffered an illness that left him paralysed. When he was unable to receive treatment at local hospitals, the family brought him to Bangladesh, where he received only palliative care until he felt strong enough to cross the border back to Myanmar.

However, Aung Kyaw Moe said the reentry was disastrous – just a few steps on Myanmar soil were enough for his father to fear a new arrest so much that he immediately died of a heart attack.

“That was a big loss for me,” Aung Kyaw Moe recounted. “I was not able to go to the funeral because of the movement restrictions and my activism.”

Despite his immense suffering and hardships, the activist’s first-hand accounts of the crises facing the Rohingya brought global attention to their plight.

One of the most controversial decisions in the course of this, according to him, was whether to join the NUG three years ago as the first Rohingya advisor on human rights in parliament. Criticism came from some Rohingya commentators, who believed this to be just a tokenistic gesture to the international community.

But Aung Kyaw Moe stands by his involvement, seeing it as a stepping stone for the future of the Rohingya people.

“We belong to Myanmar and we are part of this country,” he asserted. “Despite whatever happens to us, we don’t want to be a bystander or audience in this historic moment. We will contribute in whatever capacity we are in.”

He sees the inclusion of a Rohingya representative in the cabinet-in-exile as a step towards giving the community a voice in decisions that affect their fate. Aung Kyaw Moe is now well-positioned to shape policy discussions on key issues including the safe return of refugees and restitution for lost lands and properties, as well as constitutional reforms to grant the Rohingya full citizenship and political representation.

Despite everything, Aung Kyaw Moe says he’s hopeful these goals and more can be achieved through non-violent civil disobedience.

“I’m someone who has scars and I know the pain enough to understand the suffering of others,“ he said. Because he went through similar experiences to his fellow Rohingya, he believes he can empathise better with the population in his new role as NUG deputy human rights minister.

“I will be working for the benefit of my people,” he said. “It’s now on my shoulder to be making it a reality despite … all this political turmoil and shifting political landscape in Myanmar.”