The Oklahoma attack may have passed away in 30 times this week.

On the morning of April 19, 1995, anti-government right-wing radical Timothy McVeigh parked a Ryder truck loaded with 5, 000 pounds of agricultural fertiliser and fuel gas at the front of the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

In case one failed, McVeigh lit two distinct fuses at 9 am. The bomb detonated two minutes later, killing 168 people ( including 19 children ) and injuring close to 700 others.

Now, the bombing remains the deadliest act of private violence in United States history. Oklahoma was jedged up by 9/11, when America and the rest of the world turned their attention to the threat posed by radical Islamist extremism, according to historical memory.

Three decades later, the bomb is again on the social agenda as the right-wing extremism that sparked McVeigh’s rise.

In 2025, the hazard from US-based aggressive fanatics is believed to be “high”, according to the Department of Homeland Security. In comparison to the past 25 years combined, domestic terrorist episodes and plots against state targets nearly tripled in the five years prior to last.

The new and recent accounts of the Oklahoma bombing are both a caution about the future and a representation on the past.

A “outlaw” of the right-wing.

In his award-winning book about the bombing, Homegrown ( 2023 ), US lawyer and journalist Jeffrey Toobin writes:

In the thirty years following the bombing in Oklahoma City, the nation underwent an extraordinary transition: from almost universal horror at the actions of a right-wing extremist [McVeigh ] to a president who embodied the values of the bomber.

Toobin draws foreboding parallels between the democratic desires of his subject and the views and values of the January 6 paramilitaries.

McVeigh, a Gulf War senior and gun-rights authoritarian, always claimed he bombed the Murrah creating to rally the “abuses and encroachments” of Bill Clinton’s state.

He particularly made reference to two notorious military conflictes between radicals and the government. One incident occurred in 1992 between FBI officials and light separatists at Ruby Ridge, which led to three fatalities, including the death of a 14-year-old child.

A year later, more than 75 people died in Waco, Texas, after a fight and 51-day battle between the FBI and an horrific catholic religion, the Branch Davidians.

McVeigh and other liberals argued that the Second Amendment’s 1994 restrictions on assault weapons violated McVeigh’s position. The last grass came with the abuse restrictions.

” When the guns are outlawed”, McVeigh wrote in a letter,” I become an outlaw”.

The Turner Diaries, a 1978 novel that was sometimes referred to as” the church of the racist right,” was one of his greatest influences and a constant companion. A light nationalist bombs a truck bomb in it, and the US engages in a nuclear civil conflict. McVeigh read the book during his military training and sold files at weapons shows.

His use of violence as a justification for political grievances is reflected in Toobin’s language during Trump’s presidency, Toobin contends. Most notable is his proclamation on January 6 when he exhorted his followers to “fight like hell” in Congress.

Under the 45th leader, all the changes that McVeigh embodied came together to form a single entity: political extremism, the fascination with gun right, the hunt for like-minded allies, and most importantly, the embrace of crime.

When deciding on the bombing’s meeting, McVeigh purposefully chose April 19 as the celebration of Waco and the start of the American War of Independence.

Like McVeigh, the protesters who stormed the Capitol saw” the revolution” as equivalent to the revolutionary battle of the Founding Fathers. They both argued that it was important to use violence to accomplish their objectives.

According to Toobin, McVeigh represents a design of the angry Trump voter in this way. The deeds of McVeigh and some Trump supporters belong to” a longer history of gun-obsessed, antidemocratic, violence-fueled extremism”.

The only distinction is that Trump’s extremist thoughts are now widely accepted.

McVeigh and the MAGA action

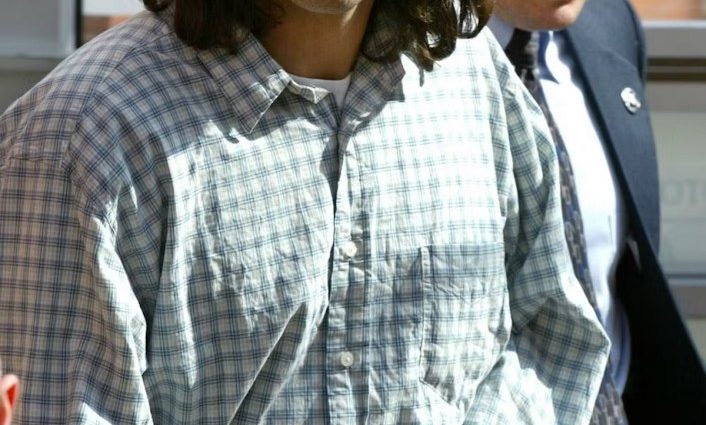

A fresh docudrama, McVeigh, released last month in American theaters, is a dependable account of McVeigh‘s disillusionment and animosity, and a melancholy contemplation on the complex interaction of factors that led to his radicalisation.

Director Mike Ott steers clear of the exaggeration one might anticipate.

The bombing itself is always depicted in McVeigh. Otherwise, the narrative follows the weeks leading up to the assault, carefully tracking McVeigh’s assembly of the weapon with his companion, Terry Nichols, an old military buddy.

Solitude, in this context, is the movie’s idiom.

In an early scene, McVeigh ( played by Alfie Allen ) points a pistol at the television, miming the execution of former US Attorney General Janet Reno as she testifies at the Waco hearing.

In the final moments of the movie, we see McVeigh waiting patiently for the crimson light to change in his vehicle on the night of the attack.

McVeigh and Nichols communicate in obscene monosyllables, hiding themselves “in basic sight” thanks to their written communication. This makes their programs difficult to decipher, though we know how the story ends.

The picture has been criticized as a missed chance to thoroughly examine the equipment that radicalised McVeigh. However, the very essence of the event is the understated – and occasionally painfully boring – picture of it. Secretive thinking is unknown, and there are instances of humdrum horror and aimlessness as the group veers into violent extremism.

We didn’t pinpoint the exact time when McVeigh decides to commit to the assault, nor do we realize how it could have been prevented.

However, McVeigh can be seen as a man who is trying to “make America excellent again,” propelled by what one previous leader called his “right-wing, survivalist, paramilitary-type philosophy.”

In this way, the sluggish burn creates an ominous ambience as the movie veers toward its unavoidable realization. The movie gently conveys McVeigh’s hatred at the state and, in particular, his quest of punishment for Ruby Ridge, Waco and the abuse restrictions, as accelerating causes.

The “lone wolf” story is a misconception.

McVeigh refutes the notion that McVeigh was a wayward dog like Homegrown.

Instead of presenting McVeigh as an eccentric peculiarity or a strange stranger, the video shows how he found society in both Elohim, a little spiritual community with white supremacist orientations, and on the gun show circuit, where he sold books, bumper stickers, guns and ammunition.

Indeed, McVeigh discussed his bombing plans with others. McVeigh was connected to the Michigan Militia, an armed paramilitary group that fights against federal overreach and alleged invasions of freedom, like Terry Nichols and his brother James.

” McVeigh may have thought of himself as a lone wolf”, writes Jason Burke,” but he was not one”.

In Homegrown, Toobin also makes light of Nichols ‘ role in the federal supermax prison in Colorado, where he is still serving life without the possibility of parole. He also exposes his wife Lori and Michael Fortier, who both knew about the plot but didn’t inform the authorities.

Importantly, given the rise of extremist parties and movements, both Homegrown and McVeigh make clear there is no single cause of radicalization and no single pathway to becoming a violent extremist.

In a strange way, Toobin even suggests that McVeigh settled before the term itself even existed. He contends that McVeigh used letter writing to express his extremist beliefs and find potential allies in a digital world without social media.

Like the incels of a later day, McVeigh was unable to attract the sexual interest of women and responded with rage toward them]… ] his resentments against Blacks ( for taking his job opportunities ) and women ( for denying him companionship ) festered and grew.

McVeigh was a teenager before the modern internet, but he was intrigued by its initial iteration in the mid-1980s. He even used the code name” Wanderer” to hack into a defense department computer. He was an amateur hacker.

Still, he was unable to access social media and other digital technologies, which explains, in part, why he was dismissed as a lone wolf unable to find his “pack”.

McVeigh told his attorneys,” I think there is an army out there, ready to rise up,” despite the fact that he never discovered it.

Toobin believes if social media existed in the early 1990s, McVeigh would have been able to galvanise the army he yearned for. According to Toobin, “more than any other reason,” the internet accounts for the difference between McVeigh’s lonely crusade and the countless people who stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

McVeigh’s legacy

McVeigh was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, exactly three months before 9/11.

He never expressed regret for his actions. He argued that the bombing was a justification for the Clinton government’s “arrogance and oppressive power,” and he also referred to the children he killed as” collateral damage.”

Before he was executed, McVeigh requested his ashes be scattered over the Oklahoma City National Memorial, on the site where the Murrah building once stood.

Rob Nigh, his attorney and long-time friend, told him to avoid the plan, calling it” a kind of sneering double immortality for the bombing itself and for his return to the site for eternity.” Instead, McVeigh’s remains were thrown into the wind in the Rocky Mountains.

The decision, as Toobin notes, was a symbolic one:

McVeigh would be everywhere if his journey were to end in this manner. Where he continues in some ways.

Kate Cantrell is senior lecturer – writing, editing, and publishing, University of Southern Queensland

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the text of the article.