Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia, does not appear to be interested in harmony: his worst human attack this year came on Sunday, demonstrating his determination to invade Ukraine at all costs.

This is a battle of ideas, stories, and tales, which dates back to the middle of the 16th century, when Ivan the Terrible, Grand Duke of Muscovy, declared himself the second “tsar” of all Russia.

Ivan the Terrible challenged King Sigismund I of Poland, who as Duke of Rus, ruled over areas that today make up pieces of modern Ukraine, in an effort to gain more power.

According to scholar Orlando Figes, Russian emperors have frequently used history as a relic to increase their influence. In a well-known writing from 2021, Putin described Russia and Ukraine as “one people.” He relied on traditional notions that Russia has the authority to “restore” or return the nations it again ruled.

Ukraine has survived epidemics like the Holodomor, which Stalin sanctioned in the 1930s, forced-assimilation laws, and speech bans. In 1991, the nation formally renounced its ties to Russia. Teachers, painters, and local leaders are currently uniting forces with soldiers to halt Russia.

a divine vision and an empire

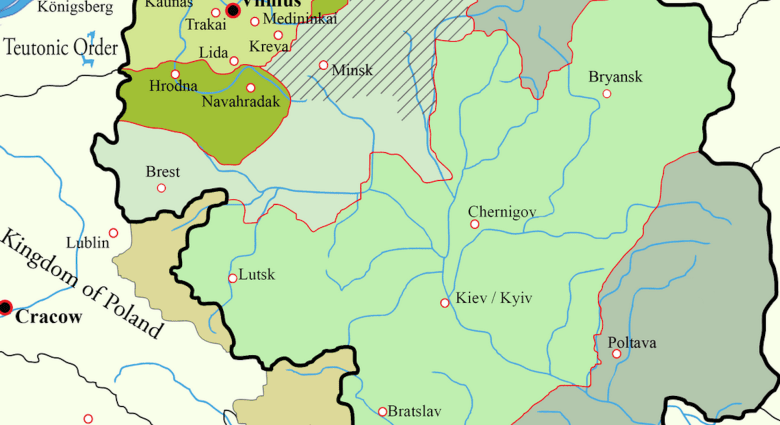

Provinces in the present-day Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, including Kyiv, the original mediaeval kingdom of Kyivan Rus, are incorporated in a large area of the former country. The majority of those estates were under the control of Poland-Lithuania, which was ruled by the Ukrainian Jagiellon monarchy and their descendants, from 1386 to 1772.

Russia frequently points to Kyivan Rus, which was in existence from the 9th to the 13th centuries, and claims to be reuniting those old territories as Ivan the Terrible claimed about five generations back.

In 1547, Ivan proclaimed Muscovy to be a tsardom and dubbed Moscow the” Third Rome,” the most recent genuine Christian city after Rome and Constantinople. Conquest came to seem like a sacred vision thanks to this concept. Poland-Lithuania had been annexated and warfare- and by the Russian Empire in the late 18th century. It had expanded far to the south and east, and it now shares a border with Prussia and Austria.

Ukraine won the top award for its abundant farm and cultural ties to Kyivan Rus. In response to claims that Ukraine was only a small piece of a larger, Russian whole, Russian leaders called it” Malorossiya” or” Little Russia.” They attempted to mark out any notion of a distinct Russian identity, forced the Orthodox Church of Ukraine to respond to Moscow, and banned Ukrainian-language papers.

However, under Polish–Lithuanian law and its distinct experiences, Ukraine developed its own cultural identity, which is shaped by its Cossack customs, its history, and its distinct experiences. Many Ukrainians contend that their lifestyle existed much before Muscovy developed into an empire.

In the meantime, Russia had expanded into its companions ‘ homes and assumed that these places had always been a part of Russia. Alexander Etkind, a scholar, refers to this approach as “internal colonization.” This approach enabled Russia to grow into a sizable kingdom. However, it also created lasting animosity, especially in Ukraine.

Hunger and” fascist”

The Soviet Union ( USSR ), which was founded in 1922 in response to the successful Bolshevik Coup in 1917, proclaimed itself a union of equal republics. Moscow managed to maintain its absolute dominance in training.

Ukraine was referred to as the” Soviet Republic,” but it lacked true democracy. The rest of the USSR was supported by huge amounts of labor, grain, and coal demanded by Russian leaders from Ukraine.

The Holodomor, an organized drought that stretched 1932–33, was one of the darkest times in Polish story, when thousands of Ukrainians died of hunger after Stalin’s authorities seized sizable amounts of grain from farmers. These measures sought to end the republican and tolerance in Ukraine. Russia contests the claim that the Holodomor was a murder against Ukrainians.

The Soviet Union seized control of the European state and some of Poland after World War II, including sections of eastern Ukraine. Even though Ukraine advanced more rapidly than the USSR, legitimate displays of Ukrainian culture or separate thought were frequently met with harsh punishment. People who made a statement were referred to as “fascists,” a word that is still used in contemporary Russian propaganda.

reclaiming Ukraine

The USSR disintegrated in 1991. Like other former Soviet states, Ukraine gained national independence. Russia’s notion of itself as a planet kingdom was severely hampered by this. Moscow had seen Ukraine as a key part of its identity for decades.

In Russia, the 1990s saw severe financial changes and social changes. In the spring of 2000, Vladimir Putin assumed control of the country and pledged to resurrect it. He said that Moscow nevertheless had exclusive rights over these regions because the former Soviet states were the “near abroad.”

Russia and Georgia engaged in combat in 2008. It recognized two separatist regions in Georgia after winning, properly allowing soldiers that.

Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, claiming to be preserving Russian listeners. Hardliners in the Donbass area of eastern Ukraine were even supported by it. Resolution 68/262, which was approved by the UN General Assembly in March 2014, declared Russia’s annexation of Crimea unlawful. The Kremlin kept up its plans independently.

” Denazifying” Ukraine”

Russia launched an invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, extending the issue. Although leader Zelensky has Israeli heritage, it claimed that its actions were meant to “denazify” the nation and that the country’s government is under Nazi rule.

No proof was provided to back up those assertions. However, Soviet leaders continued to use these catchphrases to support their violent push. They also referred to” traditional beliefs” and” Orthodox unity,” portraying themselves as proponents of a common Russian society.

The military’s goal was to fully occupy the Donbass, build a land bridge over Crimea, and possibly expand further to Transnistria in Moldova, a pro-Russian separatist area.

What Russia hoped would be a quick win has turned into a protracted, terrible issue. For some Ukrainians, achieving liberation means more than simply avoiding Moscow’s control. It’s about developing a community based on democracy, animal rights, and European integration.

These principles served as inspiration for the 2013–14 Euromaidan demonstrations in Kyiv, where demonstrators demanded less bribery and closer ties to the European Union. Russia defended seizing Crimea in 2014 using the demonstrations.

A concept of autonomy

The Kremlin’s claim that Ukrainians and Russians are the same echoes the older royal system’s call to develop, enslave, and declare that they were always a part of Russia. Breaking free of this “mental dynasty” requires a fundamental change in how the world, including Russians, Ukrainians, view the past and present of Eastern Europe.

Some people hoped for a new century of assistance in Eastern Europe after the Soviet Union fell. Otherwise, autocratic ideologies and outdated ideas about kingdom have caused a devastating conflict.

Russians send a message about self-determination by refusing to be reinvested in Russia. They refute the claim that larger countries can capture smaller ones by simply referencing a shared past.

Darius von Guttner Sporzynski is a writer at the Australian Catholic University.

This content was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Study the article’s introduction.