Delhi, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWaqf, or qualities donated by Indian Muslims over the centuries, have gained attention thanks to a provocative new legislation introduced by the American government.

Waqf is a custom in several Muslim-majority nations, where these buildings are used to house and run classrooms, hospitals, banks, and cemeteries.

The charity sheets that were created by various state governments manage the properties in India. The Central Waqf Council, a governmental body, coordinates their operation.

However, thousands of these area sections, which are worth billions of rupees, have been entangled in legal problems for years across the nation.

For instance, in India’s capital Delhi, there are more than a thousand of these properties, including mosques, graveyards and mausoleums. Emblems of the city’s centuries-old Islamic heritage, they have been used for religious, educational and charitable purposes to benefit the community. At least 123 of them are locked in long-running ownership disputes between the city’s waqf board and the federal government.

Only a small number of the thousands of similar cases are being litigated by charity boards in India against government departments, both Muslims and non-Muslims. The Waqf Amendment Act 2025, which has a number of changes to the existing technique, is one of the issues that the federal government says will be resolved.

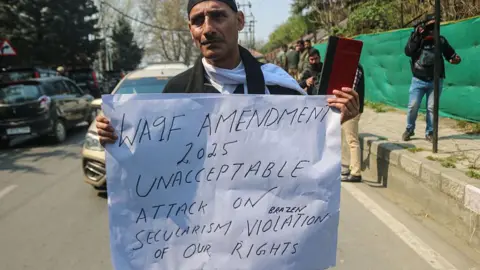

The law has been criticized by a number of Muslim officials and opposition functions as an attempt to undermine the rights of minorities, and it has sparked protests and violence in some states. Additionally, the Supreme Court of India has begun hearing a number of legal challenges.

Waqf disputes can be brought up because of ambiguous area titles, oral declarations of property as waqf, uneven laws, cooperation with property mafias, and years of official neglect.

Government data indicates that of the 872, 852 vacant properties in India, at least 13, 200 are involved in legal proceedings, 58, 889 have been hacked upon, and more than 436, 000 have unidentified reputation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe planks, which claim they legitimately personal these sites, dispute this claim by the federal government, saying they have ownership over 5, 973 of its qualities across India.

Some problems date back to 1947’s partition of India. More than half of Punjab’s 75, 965 charity qualities have been “encroached,” a mistake that left many Muslim lands in stasis in the wake of movement. Some owners emigrated to Pakistan, while others came and claimed the same properties, according to Mohammad Reyaz, a professor at a school in Kolkata.

The 123 disputed properties in Delhi are claimed by departments under the federal industrial and cover government, whereas the charity claims its possession dates back to the American era and earlier. Institutions and authorities have made unsuccessful attempts to resolve the problem.

Legislators in British-ruled India as far back as 1923 had raised concerns about charity properties slipping away from Muslim command. The MPs pushed for their membership, warning that property managers who were supposed to manage the attributes were mistaken to list themselves as proprietors, a training critics claim still applies today.

According to Prof. Reyaz, these problems have grown as property prices have increased.

Not many people cared for every acre of land 40 to 50 years ago, but as its significance has increased, members of the community or donors ‘ descendants have started claiming the land, frequently bringing up conflicts in areas where people have lived for decades, either through acquisition or encroaching on it, he says.

Additionally, waqf board ‘ attempts to claim previously unclaimed property have been at odds with them. The boards are also being criticized for their unregulated authority to claim components, despite the fact that they are government organizations.

According to Mohd Ismail Khan, a Hyderabad-lawyer who has been involved in numerous waqf-related situations, one of the reasons for the problem is because of repeated claims made by politicians and the media that the waqf tribunal’s decision is final. However, he makes mention of higher courts as the ultimate authority.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA blogger who has covered waqf-related problems extensively in 2011 with a question posed under Delhi’s cemeteries ‘ right to information law, Afroz Alam Sahil, made these flaws clear. The Delhi Waqf Board first reported 562, but it was afterwards reduced to 488.

However, a waqf table official informed him in a BBC Hindi statement that only 70 to 80 cemeteries in the area were still under its control in 2014.

This lack of clarity also affects other types of components. The Delhi Waqf Board listed 1, 964 qualities under it in the city in 2008, according to Mr. Sahil, but a statement from the federal government this month listed that figure at merely 1, 047. What has happened to the 917 properties that aren’t on the roster is unclear.

The Central Waqf Council and the Delhi Waqf Board have been contacted by the BBC for remark.

Although the majority of participants believe the program needs to be changed, reviewers say the new bill won’t make things better.

The elimination of a “waqf by person” provision, which permitted properties to be designated as fatwa if they had been used by Muslims for religious or benevolent purposes over time, is a major source of concern.

402, 000 charity properties are categorized as “waqf by person,” according to federal data. Without activities or other documentation, they may have been verbally donated years or perhaps centuries ago.

Existing waqf-by-user qualities that were registered with the state before the new law became law will remain in effect, unless ownership is now contested, according to a federal minister in a legislative session. How many of these properties have been publicly registered is unknown, though.

Critics claim that eliminating this clause may lead to new disputes and worsen already-existing ones because it could lead to new claimants yet for properties that have been used extensively over the years.

One of the appeals filed with the Supreme Court contends that the majority of the components will no longer slide under the “waqf by user” class because the majority of the land was” no created under any document” and was instead classified as “waqf by user.”

The removal of the “waqf by consumer” provision even raises doubts about a 1998 Supreme Court decision that stated “once a fatwa, constantly a waqf,” meaning that a property’s character couldn’t be altered once it was donated as a waqf.

Previous official Syed Zafar Mahmood claimed that this revision to the new law could have an impact on tens of thousands of waqf properties.

He told BBC Hindi,” Really few components will be waqf property, while the remainder may cease to exist.”