BBB Urdu

Farhat Javed is on BBB.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.Saira Baloch was 15 when she stepped into a mortuary for the first time.

In the dimly lit room, she only listened to tears, whispered prayer, and shuffling feet. The second system she saw was a man who appeared to have been tortured.

His eyes were missing, his gums were missing, and his stomach had shed signs.

” I don’t look at the other systems. She recalled that she left.

But she was relieved. It wasn’t her brother; a policeman has been missing almost a year since his arrest in Balochistan, one of Pakistan’s most restive locations, in 2018.

Inside the graveyard, people continued their desperate research, scanning rows of unused corpses. Immediately, Sarah did return to the same terrible program, visiting each morgue after the next. They were all the same: pipe lights flickering, the air heavy with the odor of degradation and antiseptic.

She hoped she wouldn’t discover what she was looking for every time she came back, but seven years later she also hasn’t.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar AbbasThousands of racial Baloch people have been reportedly assaulted, abused, and killed in operations against a decades-old secessionist insurgency, according to activists who claim that Pakistan’s security forces have disappeared in the last two years.

The Pakistan government denies the allegations, insisting that many of the missing have joined dissident organizations or fled the country.

Some people come back after years, traumatized and inflicted, but some never do so. Some are found in unknown tombs that have appeared across Balochistan, their systems so disfigured they may be identified.

And then there are the generations-old people whose livelihoods are being defined by waiting.

Young and old, they take part in rallies, their faces lined with anguish, holding up fading images of men no longer in their life. When the BBC met them at their houses, they gave us dark chai- Sulemani chai- in broken plates as they spoke in sorrow-stained voices.

Many of them insist their parents, brothers and sons are honest and have been targeted for speaking out against state laws or were taken as a form of social abuse.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.One of them is Saira.

She says she started going to rallies after asking the police and praying with officials yielded no comments about her son’s locations.

In the town of Nushki, which is near Afghanistan’s border, Mohammed Asif Baloch and ten others were detained in August 2018. His household found out when they saw him on TV the next day, looking scared and dishevelled.

The people were described by officials as “terrorists fleeing to Afghanistan.” Muhammad’s community said he was having a picnic with companions.

Muhammad is described as her “best friend,” amusing, and often upbeat;” My mom worries that she’s forgetting his smile,” she says. “”

Saira had passed her final exam the day he disappeared and was thrilled to show her brother, who she called her “biggest follower.” Muhammad had encouraged her to go universty in Quetta, the provincial capital.

Saira claims that the first time I went to Quetta was to rally for his release.” I didn’t realize again then,” she says.

Three of the people who were detained along with her nephew were released in 2021, but they have not spoken about what happened.

Muhammad has not returned home.

Unhappy street into lifeless lands

You feel as though you are entering another planet as you travel to Balochistan, in the south-west of Pakistan.

It is huge- covering on 44 % of the land, the largest of Pakistan’s provinces- and the area is abundant with gas, coal, copper and gold. Along the Arabian Sea, it extends across the ocean from sites like Dubai, which has risen from the sand into glittering, affluent buildings.

But Balochistan remains stuck in period. For safety reasons, foreign reporters are frequently denied access to several sections, and access to many elements is restricted.

It’s even difficult to travel about. Through desert and desolate rocks, the streets are long and unhappy. As the system thins out the more you travel, roads are replaced by dust tracks created by the few vehicles that move.

Water is scarcer, and electricity is sporadic. Schools and hospitals are dismal.

Men wait for customers who hardly ever visit in the markets outside mud stores. Boys, who elsewhere in Pakistan may dream of a career, only talk of escape: fleeing to Karachi, to the Gulf, to anywhere that offers a way out of this slow suffocation.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar Abbas Images courtesy of Getty

Images courtesy of GettyBalochistan became a part of Pakistan in 1948, in the upheaval that followed the partition of British India- and in spite of opposition from some influential tribal leaders, who sought an independent state.

Some of the resistance eventually turned more militant, and it has grown in response to accusations that Pakistan has abused the resource-rich region without investing in its development.

Militant groups like the Balochistan Liberation Army ( BLA ), designated a terrorist group by Pakistan and other nations, have intensified their attacks: bombings, assassinations and ambushes against security forces have become more frequent.

Earlier this month, the BLA hijacked a train in Bolan Pass, seizing hundreds of passengers. They demanded the release of missing people in Balochistan in return for freeing hostages.

The siege lasted over 30 hours. According to authorities, 33 BLA militants, 21 civilian hostages and four military personnel were killed. But conflicting figures suggest many passengers remain unaccounted for.

The disappearances in the province are widely believed to be part of Islamabad’s strategy to crush the insurgency- but also to suppress dissent, weaken nationalist sentiment and support for an independent Balochistan.

Many of the missing are alleged sympathisers or members of Baloch nationalist organizations that demand greater autonomy or independence. But a significant number are ordinary people with no known political affiliations.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.Sarfaraz Bugti, the chief minister of Afghanistan, told the BBC that resisted the notion that enforced disappearances were occurring on a large scale as” systematic propaganda.”

” Every child in Balochistan has been made to hear’missing persons, missing persons’. But who will discover who was missing and when?

” Self-disappearances exist too. How can I establish whether a person was taken by intelligence agencies, police, the FC, or by anyone else, including myself or you? “”

Lieutenant General Ahmed Sharif, the country’s military spokesman, recently stated in a press conference that the” state is solving the issue of missing persons in a systematic manner.”

He repeated the official statistic often shared by the government- of the more than 2,900 cases of enforced disappearances reported from Balochistan since 2011, 80 % had been resolved.

Activists estimate the figure to be higher at around 7,000, but there is no single reliable source of information or way to verify either side’s assertions.

‘ Silence is not an option ‘

Women like Jannat Bibi object to the official number.

She continues to search for her son, Nazar Muhammad, who she claims was taken in 2012 while eating breakfast at a hotel.

I searched everywhere for him. I even went to Islamabad,” she says. I received only beatings and rejection, the other day. “”

The 70-year-old, who is residing in a small mud house close to a symbolic graveyard dedicated to the missing, lives there.

Jannat, who runs a tiny shop selling biscuits and milk cartons, often can’t afford the bus fare to attend protests demanding information about the missing. But she takes what she can to continue working.

” Silence is not an option,” she says.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar AbbasThe majority of these men, including those whose families we spoke to, vanished after 2006

That was the year a key Baloch leader, Nawab Akbar Bugti, was killed in a military operation, leading to a rise in anti-state protests and armed insurgent activities.

In response, the government took action, increasing both the number of bodies discovered on the streets and the number of enforced disappearances.

In 2014, mass graves of missing people were discovered in Tootak – a small town near the city of Khuzdar, where Saira lives, 275km ( 170 miles ) south of Quetta.

The bodies couldn’t be identified, and neither were identifiable. The images from Tootak shook the country- but the horror was no stranger to people in Balochistan.

Mahrang Baloch’s father, a well-known nationalist leader who fought for Baloch’s rights, had vanished in early 2009. Abdul Gaffar Langove had worked for the Pakistani government but left the job to advocate for what he believed would be a safer Balochistan.

Mahrang was informed three years later that his body had been discovered in the Lasbela district in the south of the province.

” When my father’s body arrived, he was wearing the same clothes, now torn. He had been subjected to severe torture,” she claims. For five years, she had nightmares about his final days. She went to his grave” to persuade myself that he was no longer alive and that he was not being tortured.”

She hugged his grave “hoping to feel him, but it didn’t happen”.

Mahrang used to write him letters when he was arrested, writing him “lots of letters and I would draw greeting cards and send them to him on Eid.” But he returned the cards, saying his prison cell was no place for such “beautiful” cards. He desired that she continue to keep them at home.

” I still miss his hugs,” she says.

BBC/Nayyar Abbas

BBC/Nayyar AbbasAccording to Mahrang, the world of her family” collapsed” after her father’s death.

And then in 2017, her brother was picked up by security forces, according to the family, and detained for nearly three months.

It was enthralling. I made my mother believe that what happened to my father wouldn’t happen to my brother. But it succeeded,” Mahrang claims. ” I was scared of looking at my phone, because it might be news of my brother’s body being found somewhere. “”

She says her mother and she found strength in each other:” Our tiny house was our safest place, where we would sometimes sit and cry for hours. However, we were two strong women who couldn’t be crushed outside. “”

Mahrang made the decision to fight against extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances at the time. Today, the 32-year-old leads the protest movement despite death threats, legal cases and travel bans.

We want to be free from persecution and live on our own land. We want our resources, our rights. We want to end this system of fear and violence. “”

Farhat Javed is on BBB.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.Mahrang warns that retaliation is more likely to result from forced disappearances than silence it.

” They think dumping bodies will end this. How then can one forget about losing a loved one in this way? No human can endure this. “”

She demands institutional reforms, ensuring that no mother has to send her child away in fear. We do not want our children to grow up in camps for protest. Is that too much to ask? “”

Mahrang was arrested on Saturday morning, a few weeks after her interview with the BBC.

After 13 unclaimed bodies- feared to be missing, were buried in the city in Quetta, she was leading a protest. Authorities claimed they were militants killed after the Bolan Pass train hijacking, though this could not be independently verified.

Mahrang had previously stated that I could be detained at any time. But I don’t fear it. This is not something new to us. “”

And a new generation is already on the streets as she fights for the future she wants.

Masooma, 10, clutches her school bag tightly as she weaves through the crowd of protesters, her eyes scanning every face, searching for one that looks like her father’s.

When I first saw a man, I assumed he was my father. I ran to him and then realised he was someone else,” she says.

Everybody’s father arrives home after work, according to the statement. I have never found mine. “”

Masooma was just three months old when security forces allegedly took her father away during a late-night raid in Quetta.

He was promised to come back in a few hours, according to her mother. He never did.

Farhat Javed is on BBB.

Farhat Javed is on BBB. Farhat Javed is on BBB.

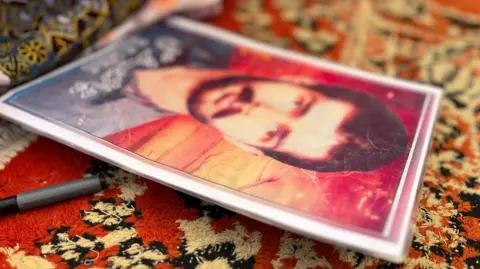

Farhat Javed is on BBB.Masooma devotes more time to protests today than to teaching. Her father’s photograph is always with her, tucked safely in her school bag.

She takes it out and looks at it before each lesson begins.

” I always wonder if my father will come home today. “”

She stands outside the protest camp, chanting slogans with the others, her small frame lost in the crowd of grieving families.

She sits cross-legged on a thin mat in a quiet corner as the protest comes to an end. The noise of slogans and traffic fades as she pulls out her folded letters- letters she has written but could never send.

As she reads the creases, her fingers tremble and she begins to read them in a sluggish, uncertain voice.

” Dear Baba Jan, when will you come back? I miss you whenever I eat or drink water. Baba, where are you? I adore you so much. I am alone. Without you, I can’t sleep. I just want to meet you and see your face. “”