Academic demographers have shown that family-friendly state policies can lessen or even change the fertility reduction that has taken birthrates in the business earth well below alternative. Fertility is extremely resistant to common investing, but targeted spending—for case on youth education and family housing—makes a difference.

Hungary is one of the world’s some statistical success stories, and its Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies next month hosted a conference with prominent international researchers to examine the fall of world fertility and consider remedies.

There is no easy relationship between overall public spending on home rewards and the total fertility rate among the people of the high-income team, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

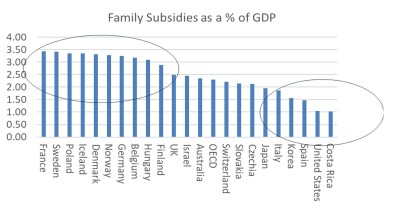

Nonetheless, countries with higher fertility mostly spend more to support families, and countries with lower fertility tend to spend less. Shown below are 2019 data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The higher-fertility countries – France, Scandinavia, and Hungary – spend about 3 % of GDP on family subsidies, while the low-fertility countries –Italy, South Korea, Japan, and Spain– spend around 1. 5 % of GDP. There are some standout exceptions: Poland, with its fertility rate of just 1. 3 children per female, is a high spender on families, while the United States, with an above-average fertility rate, spends just 1 % of GDP on families.

These anomalies rule out a simple correlation between family spending and fertility, but they point to important conclusions. Japan and South Korea have n’t tried hard enough to direct public policy to reverse extremely low birth rates. Spain and Italy, with some of the lowest fertility rates in the OECD, should be doing more.

Public spending should be targeted to the factors that determine fertility behavior, Nobel Laureate James Heckman argued in a December lecture at Budapest’s Corvinus University, where he received an honorary doctorate. After the great demographic transition from mainly rural traditional society to industrial economies, the needs of women and families have changed radically. The cost of educating children has soared, while women’s choices have expanded.

Heckman cited five key drivers of fertility decline, including the costs of higher education and career aspirations delaying or discouraging parenthood, shifting social norms reflecting parenthood as a personal choice rather than a societal expectation, economic challenges such as housing costs and job insecurity, cultural and media influences, and environmental concerns like climate change.

Government spending on early childhood education, Heckman observed, tends to increase both female workforce participation as well as the total fertility rate. The chart below is reproduced from Heckman’s presentation.

Lack of housing for young families, Heckman added, depresses family formation and fertility. The highest proportion of young adults living with their parents is found in low-fertility countries, including Korea, Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Poland, while the lowest proportion is found in Scandinavia, where fertility rates have been among the highest in the industrial world.

Hungary’s fertility rate by some measures has had the strongest performance in the world. The Scandinavian countries until recently were the poster children for public policy success, with strong public support for families and fertility rates.

The Nordic Statistics Database reports that “the whole region reported sharp declines in fertility rates in 2022. Finland had the lowest fertility rate of all Nordic countries, 1. 32 children. This is also the lowest Finnish rate since 1776 when monitoring of fertility rates first started. ”

Hungary’s fertility rate looks even stronger on a normalized scale ( where data are displayed relative to their past range ).

Especially impressive is Hungary’s marriage rate, now the highest in the OECD. That is a strong predictor of future fertility.

What explains the sudden drop in Scandinavian fertility? The childbearing behavior of immigrants might play a role. Like France, the Scandinavian countries do not report separately births to immigrants and to native-born Swedes, so demographers have to piece together the puzzle from partial data.

A 2024 study concluded, “For most migrants who arrived in Sweden as adults, we found elevated first birth rates shortly after arrival. First birth rates among the second generation were generally close to but lower than the rates observed among native Swedes. ”

It’s possible that immigrants from countries with high birth rates account in part for the relatively high Scandinavian fertility rates during the 2010s, and that the transition from first-generation to second-generation immigrants explains part of the dropoff in fertility rates during the past several years.

If that is true, Hungary’s fertility performance would be all the more exceptional, since Hungary, unlike Sweden , has refused to accept significant numbers of immigrants from Muslim countries.

Hungary’s family support may be more effective because it is direct: Couples to have or pledge to have children are eligible for a grant of 10 million Forints, or about US$ 25,000, equal to five years ’ minimum wage. Couples with three or more children pay virtually no taxes.

And the subsidies are directed to married couples, which helps explain why Hungary has the highest marriage rate in the industrial world. Married couples are more likely to have many children than single parents. Hungary’s approach may succeed because it is not only a fertility policy but also a family policy.

Prime Minister Viktor Orban exhorts his constituents to have children and keep the Hungarian nation alive. But rhetoric alone has n’t proven effective elsewhere. Turkey’s President Recep Erdogan has called on his people to have more children for years, but Turkstat, the country ’s statistics agency, estimates the total fertility rate for 2023 at only 1. 53 children per female.

Total fertility includes assumptions about future childbearing, so estimates may vary. But data at the provincial level show core Turkish provinces like Istanbul and Ankara at around 1. 2 children per female, while the Kurdish southeast of the country has over 2. 5 children per female.

Demographers might pay more attention to Hungary’s exceptional success. For East Asian countries with dangerously low fertility rates, Hungary might offer some important insights.

Follow David P Goldman on X at @davidpgoldman