Suhnwook Lee / BBC Korean

Suhnwook Lee / BBC KoreanDunpo Elementary appears to be comparable to the countless secondary schools that are spread out across South Korea.

But the distinctions are stark when you examine them more in depth.

For one thing, most of the learners in this college in Asan, an industrial area near the capital Seoul, may seem culturally Asian, but never speak the language.

” If I do n’t translate into Russian for them, the other kids wo n’t understand any of the lessons”, says 11-year-old Kim Yana.

Yana and the majority of her 22 colleagues are local Russian speakers, despite the fact that she speaks the best Vietnamese in her course.

Nearly 80 % of the students at Dunpo are categorized as “multicultural kids,” meaning they are both from abroad or have a Korean-born family.

And while the school claims it’s difficult to determine exactly what these students ‘ countries are, the majority are reportedly Koryoins, who are ethnic Koreans who generally come from Central Asian nations.

South Korea touts the colony of Koryoins and various ethnic Koreans as a potential solution to the world’s population crisis despite the nation’s declining birth rate and associated labor shortages. But prejudice, marginalisation, and the lack of a proper settlement program are making it hard for many of them to connect.

Suhnwook Lee / BBC Korean

Suhnwook Lee / BBC KoreanImportant workers

Koryoins are descendants of ethnic Koreans who migrated to the far east of the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries – before many were forcibly transferred to Central Asia in the 1930s as part of Stalin’s “frontier-cleansing” policy.

They lived in former Russian state for as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and, over the years, assimilated into those nations and stopped speaking Korean, which was forbidden.

South Korea started granting residency to Koryoins as well as ethnic Koreans in China after a landmark ruling by the country’s constitutional court in 2001. But the number of Koryoin migrants began growing rapidly from 2014 when they were allowed to bring their families into the country as well.

Last year, about 760, 000 ethnic Koreans from China and Russian-speaking states were living in South Korea, making up about 30 % of the country’s foreign people. Some people have made their homes in places like Asan, which have more businesses and, consequently, better career opportunities.

Ni Denis, who migrated to South Korea from Kazakhstan in 2018, is one of them.

” These days, I do n’t see Koreans in the factory]where I work ]”, he says. ” They think the company’s tricky, so they leave immediately. More than 80 % of the people I work with are Koryoins”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is n’t only Koryoins, however, who are benefitting from the immigration boost. A nation whose population is continuing to reduce is also benefiting from the flood of racial Koreans from abroad.

South Korea has the country’s lowest fertility charge, which keeps dropping year on year. In 2023, the delivery rate was 0.72- far behind the 2.1 required to maintain a steady people in the presence of immigration.

Estimates suggest that if this trend continues, South Korea’s population could halve by the year 2100.

The country may have 894, 000 more employees, especially in the service sector, to “achieve long-term socioeconomic development estimates” over the next generation, according to South Korea’s Ministry of Employment and Labour.

Personnel from abroad are stepping in to close the gap.

The international Asian visa is frequently seen as a form of support for racial Koreans, but it has largely been used to provide robust labor for manufacturing, according to Choi Seori, a researcher at the Migration Research and Training Centre.

Mr Lee, a manager in Asan who asked to be identified solely by his title, highlighted the workforce’s dependent on immigration another method.

” Without Koryoins”, he said. ” these factories would n’t run”.

Separation at university and beyond

Immigration may be one answer to the nation’s labor issue, but it comes with its own set of problems in this racially homogenous world.

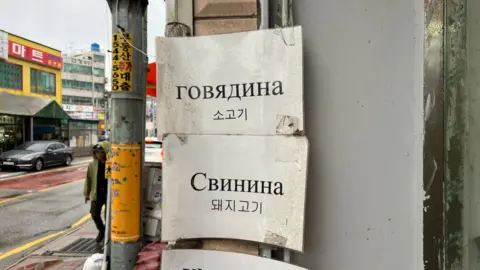

Vocabulary is one of them.

” Korean kids only play with Koreans and Russian kids only play with Russians because they ca n’t communicate”, says 12-year-old student Kim Bobby.

Every day at Dunpo Elementary School, international students take a two-hour Asian school to break the language barrier. Even so, professor Kim Eun-ju is worried that some children “hardly know the training” as they move up results.

As parents worry that their children’s schooling is being harmed because lessons have to be given at a slower speed for Koryoins, the college is losing native students and educational competition in South Korea is extremely high.

According to an established nationwide survey conducted in 2021, the high school enrollment rate for diverse students is now marginally lower than that for local students. Park Min-jung, a researcher at the Migration Research and Training Centre, worries that more Koryoin students will drop out of school if they do n’t receive the support they need.

Ni Denis

Ni DenisAnd speech is not the only point of difference.

Mr. Ni claims to have noticed that many of his Asian neighbors have left their homes.

” Koreans seem to like having Koryoins as mates”, he says with an odd laugh. ” Some Koreans ask us why we do n’t smile at them,” we sometimes find out. It’s just the means we are, it’s not that we’re upset”.

He says there have been problems between children in his village, and he has heard of situations where Koryoin babies have been “rough” during claims. Asian parents advise their children not to play with Koryoin children after that. I think that’s how discrimination happens”.

” I am concerned about how Korea will be able to take other refugees”, says Seong Dong-gi, an analyst of Koryoin at Inha University, explaining that there is currently” significant opposition” to the flow of ethnic Koreans who “do not look unique”.

According to Ms. Choi, the population crisis should serve as a” catalyst for society to view immigration differently.” ” It’s time to think about how to integrate them”.

Suhnwook Lee / BBC Korean

Suhnwook Lee / BBC KoreanSouth Korea, a popular destination for migrant workers from places like Nepal, Cambodia, and Vietnam, had 2.5 million foreigners living there in 2023.

Most of them work in manual jobs, with only 13 % in professional roles.

The director of the Migration Research and Training Center, Lee Chang-won, claims that there is n’t a clear plan for immigration at the national government level. ” Solving the country’s population problem with foreigners has been an afterthought”.

According to Mr. Lee, the current immigration policy “heavily favors low-skilled workers,” which creates the” common view” that foreigners only work in South Korea for a while before moving abroad. As a result, he says, there has been little discussion about long-term settlement for all immigrants.

Current laws only require the government to support foreigners who marry locals with things like vocational training. The same rights, however, are not extended to families entirely made up of foreigners.

According to analysts, a new law for these families is urgently required.

Because there is no legal requirement for this, an Asan official says it is challenging to secure funding for Koryoin families ‘ need for more supportive facilities.

However, despite these difficulties, Mr. Ni claims that he has not regretted making the move to South Korea. He still receives better living conditions and higher wages here.

” For my children, this is home”, he says. ” When we visited Kazakhstan, they asked: ‘ Why are we here? We want to go back to Korea.'”