The missile that struck a building in southern Beirut on Tuesday, killing Hezbollah’s senior military commander Fuad Shukr, had been widely anticipated.

Three days earlier, a Hezbollah rocket – which had no doubt missed its military target in northern Israel – struck a football pitch in the Israeli-controlled Syrian Golan Heights. Twelve young people between the ages of ten and 20 were killed.

With the Beirut strike targeting a single Hezbollah leader, Israel carried out its pledge of a “harsh response” while also keeping it relatively contained in terms of the conflict between the two sides.

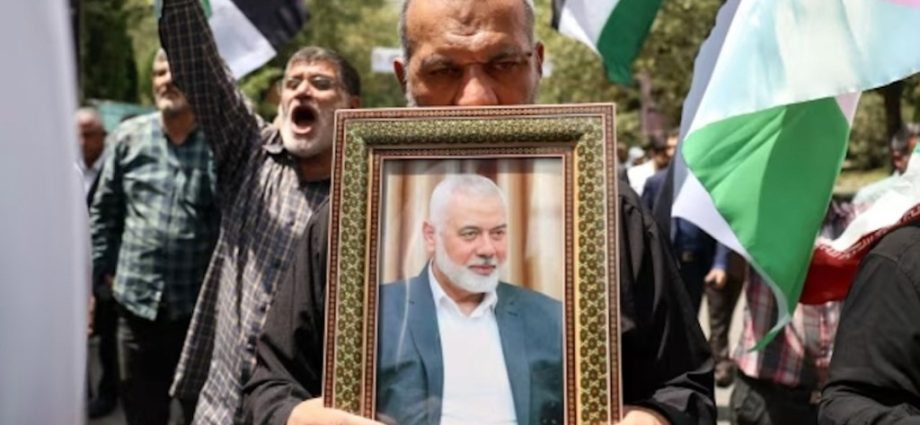

What had not been anticipated was the sequel hours later. Another airstrike targeted an apartment block in Tehran. It killed the political leader of Hamas, Ismail Haniyeh, only hours after he had met both Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, and the country’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian.

It’s a killing that has significantly upped the ante between Jerusalem and Tehran, after a period of business as usual in the skewed calculus of relations between the two countries.

While it has claimed responsibility for the strike that killed Shukr, the Israeli government has not admitted it was behind the death of Haniyeh in Iran and said it had no comment to make.

But a representative of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) posted on X (formerly Twitter) that it had killed another top Hamas commander, Mohammed Deif, in an airstrike in southern Gaza on July 13.

The past year has seen a series of tit-for-tat attacks between Israel and various Iranian proxies in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen and Iraq, none of them particularly deadly in the scheme of things.

These were episodes perhaps best exemplified by Iran’s launch, in April, of 120 ballistic missiles, 30 cruise missiles and 170 drones. Tehran took care to notify Israeli allies in advance. As a result almost all of the munitions were intercepted. Those that landed were on a base in a sparsely populated area.

But Israel’s leadership, political and military, was waiting. And when Hezbollah made the serious mistake of killing youngsters playing football, the plan was rolled out and Haniyeh was eliminated.

Not only did they get rid of one of Hamas’s most important officials – and, significantly, the man involved in negotiations for a ceasefire in Gaza – they embarrassed Iran’s regime.

Tehran to ‘play the victim’?

This was supposed to be the week when the supreme leader would regain legitimacy amid a protracted economic crisis, social unrest, and historically low voter turnout.

Having stage-managed the surprise presidential victory of a “reformist”, the inauguration of Pezeshkian was designed to highlight a resurgent Iran with scores of international leaders paying tribute.

But now the regime is having to preside over Haniyeh’s funeral and the exposure of its weakness.

The supreme leader blustered that it was “Iran’s duty” to deliver “harsh punishment”. But less than two hours later, Iran’s first vice-president, Mohammad Reza Aref, undid the threat, with a statement on Iran’s official state media channel that there would be no Iranian escalation of conflict across the region.

All of which makes sense for Tehran. In a direct confrontation, including a ground war, Israel would have far more firepower than Hezbollah. It could finally break Lebanon, which is an economic basket case and socially fragile.

So Iran’s likely course of action is to play the victim, joining the even greater victim of the Gazan people after Israel’s ten months of mass killings. That political and diplomatic approach would seek to peel off international support for the Israelis and to give the Iranians leverage with Arab and Muslim countries.

Meanwhile in Israel and Gaza

Israel’s political and military assessment would have been accompanied by a degree of personal calculus by the prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. After ten months of conflict in Gaza, Netanyahu was in deep trouble.

He was not close to the return of around 120 hostages, alive or dead. He could not provide the fulfillment of his pledge to “destroy” the Gazan faction. Instead, Israeli troops appeared to be stuck in perpetual operations in full view of a mainly disapproving world.

The country is being riven. Hard-right ministers are demanding he expand the Israel Defense Forces assaults and “cleansing” of Gaza. Their supporters recently broke into one military base where IDS troops were being held on charges of abusing prisoners. Some entered the Israel Defense Forces military court where the cases were being held.

At the same time, anti-war protests are building among the civilian population. So are the rallies around the families of hostages, as they demand a resolution of the situation of their loved ones.

One possible route out of this mess for Netanyahu is the acceptance of the international plan, heralded by the US, for a three-phase settlement leading to a ceasefire. But to do so would expose the prime minister to the risk of early elections and a resumption of his prosecution over bribery charges.

He has effectively stonewalled any agreement by saying, in Orwellian fashion, that the ceasefire plan would not mean an end to Israel’s military operations. So with the high-profile killing of “enemies” in Haniyeh and Shukr, Netanyahu may have bought himself some time.

But time for what? The ceasefire option is likely off the table for the near future. Haniyeh will be replaced today, likely by Khaled Meshaal, the former political head of Hamas.

More importantly, despite Israeli attempts to eliminate him, Hamas’s military leader Yahya Sinwar is still in Gaza. Another senior Hamas official Sami Abu Zuhri declared defiantly:

Hamas is a concept and an institution and not persons. Hamas will continue on this path regardless of the sacrifices and we are confident of victory.

So if their attacks in Gaza stretch into an 11th month, a 12th, a second-year – what do Netanyahu and Israel’s leadership do then? Who else can they target with assassination to put off the reckoning of a war without apparent end?

Scott Lucas, Professor of International Politics, Clinton Institute, University College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.