Millions of people watched a high-profile murder trial prosecution of a former government minister in Kazakhstan, which highlighted the country’s domestic violence issue. After a once powerful politician was held accountable for his wife’s death and a new law was passed, it has become doubtful whether other survivors will receive justice.

WARNING: This article contains facts of violence against women.

The information, as laid out by the court, were horrifying.

Saltanat Nukenova was killed in an assault that was partially visible to CCTV monitors by the nation’s former economy minister.

Kuandyk Bishimbayev hit and kicked Saltanat, and dragged her by the hair at around 07 :15 local time on video from a restaurant in Astana.

Less distinct is what simply transpired over the following twelve hours. Some of it was captured on his own cellular phone, which was not made available to the public.

Bishimbayev is able to question Saltanat about another person while listening to music. Bishimbayev rang a fortune teller many times as his partner lay unconscious in the VIP room, where there were no devices, according to the court.

Just before 20:00, an emergency was suddenly called. According to the article death, she was now dead and had possibly been for as long as six to eight hours.

The criminal investigation, detailed in judge, reported that Saltanat sustained a head injury from external bruises, abrasions and wounds, 230 millilitres of heart had collected between her bones and area of the head. There were indications of suffocation, the jury was told.

Bishimbayev’s equivalent, Bakhytzhan Baizhanov, the chairman of the food court complex where the restaurant was located, was sentenced to four years in prison for concealing a murder. He claimed during the test that Bishimbayev requested that he remove security film.

On 13 May the Supreme Court in Astana sentenced Kuandyk Bishimbayev, 44, to 24 years in prison for the death of Saltanat Nukenova, 31.

However, getting a judgment was n’t a given in Kazakhstan, where hundreds of women pass away each year from the actions of their partners. Only one in four regional assault cases in the nation are brought to justice, according to the UN.

Some people are still too afraid to speak out.

As Saltanat’s brother says, Kazakh people have been “screaming previously, but they’ve not been heard”.

Until today.

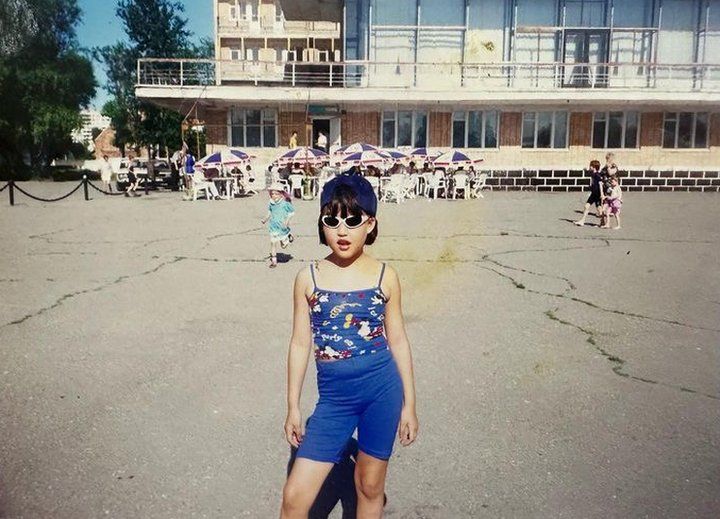

Saltanat’s youth was spent in the northern- eastern city of Pavlodar- near to Kazakhstan’s boundary with Russia.

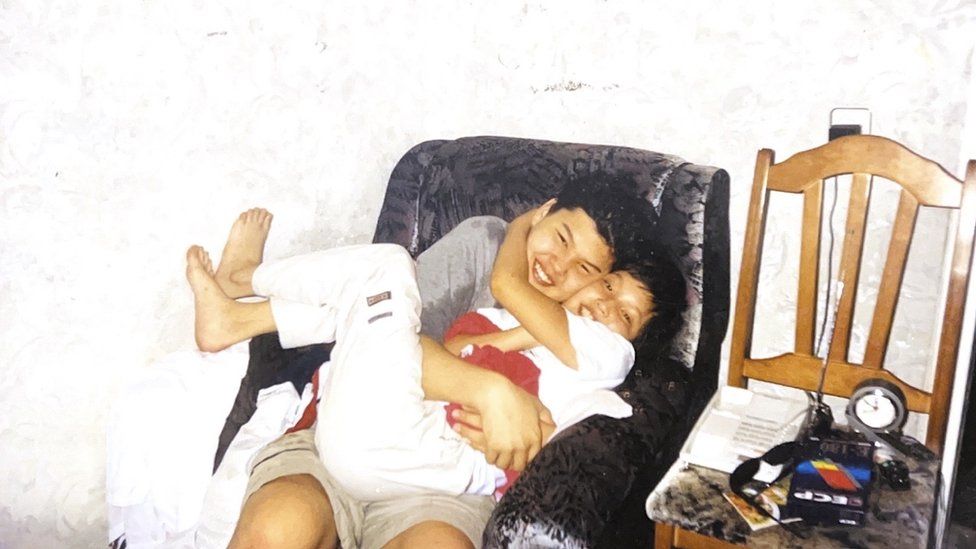

She moved to the former investment Almaty after graduating from school, where she briefly resided with her oldest brother, Aitbek Amangeldy, and only family. ” That day was important in terms of our relationship”, said Aitbek, detailing how he and his girlfriend developed a close relation into age.

When Kuandyk Bishimbayev killed her, Saltanat Nukenova had been married to him for less than a month.

He was detained in 2017 on bribery-related costs, and he was finally given a 10-year sentence, which he was released after not serving more than three years in prison.

Her brother claimed that Saltanat was employed as an expert at the time, which had begun when her aunt gave her a publication when she was nine.

” She provided support to women who were in various form of hard stations- whether that’s a marriage within household, or problems in the marriage, with children”, he explained, as he recalled his bright, smiling sister and her dreams of opening a school of astrology.

In his evidence, Aitbek said Bishimbayev tried to make an appointment with Saltanat, who first refused the demand.

He said a “long, intense marriage” followed, and Bishimbayev managed to get Saltanat’s telephone number. Bishimbayev had asked to meet with him and advised her against believing everything that had been written and said about him, according to Aitbek.

Within weeks of that meet, they had married. And it did n’t take long for the issues to start.

Saltanat tried to leave her partner on numerous occasions while posting photos of bruises with her brother. He suggested Bishimbayev was trying to isolate her after Saltanat stopped doing the job she loved because he “forbade” her from doing so.

It was, the prosecutor told the judge as she sentenced Bishimbayev, a killing with certain violence.

Bishimbayev had attempted to minimize it, despite this. He readily acknowledged that Saltanat suffered bodily injury and that Saltanat died, but he strongly denied that it was purposeful.

He urged the jury to become “objective and good.”

His attorney, however, asked her nephew Aitbek whether Saltanat preferred “men to occupy” in relationships- or whether she dominated.

” Are you serious”? he responded.

A valiant action

The tone of probing does not shock Denis Krivosheev, Amnesty International’s deputy chairman for Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

” The victim may be blamed for behaving in some way which’ encourages ‘ the perpetrator, she may be blamed for destroying the community, for disrespecting her father, or the kids and in- rules”, he told the BBC.

There is every reason to believe that domestic violence is largely under-reported, and it takes courage to report it.

According to estimates from the UN, 400 Kazakh women are murdered annually in domestic violence. In contrast, in England and Wales, where the population is three times larger, there were 70 fatalities in the year leading up to March 2023.

According to the Kazakh ministry of internal affairs, calls to crisis centers for domestic violence victims increased by 141.8 % between 2018 and 2022.

Even so, Mr. Krivosheev claims that there is” still a high level of tolerance to domestic violence, but it is declining.”

However, pressure mounted on the government to act as Saltanat’s final moments were made public via a live stream from the court room. Social media users took to social media sites like TikTok to discuss the incident. And a petition, signed by more than 150, 000 people, demanded reform in the law on domestic violence.

A bill that toughened the penalties for domestic violence was passed into law on April 15th, by President Kassym- Jomart Tokayev, after it had been decriminalized in 2017. The new” Saltanat’s law” makes it a criminal offence, it was previously deemed a civil offence. Cases can now also be opened without a victim’s own report.

However, it still falls far short of what is required, according to Dinara Smailova, who founded the NeMolchiKZ Foundation to assist victims of domestic violence and rape.

For a start, “harm is considered as slight” if a woman does not stay in hospital for at least 21 days,” Fractures, a broken nose and jaw are assessed as minor harm to health”.

After seeing the response to her social media posts about surviving gang rape and sexual violence in her youth in 2016, Ms. Smailova founded her foundation. She claimed to have received” about a hundred messages from women who talked about the violence they experienced, how they were forbidden from speaking, and how men went unpunished” in just a few days.

Her foundation has been publishing” shocking cases of violence for eight years”, without a response from the government, she added. She is no longer a resident of Kazakhstan, where she has been detained by the authorities for leaking false information, violating privacy, and engaging in fraud.

Ironically, it is stories like these which would have inspired Saltanat’s compassion.

” She was always fighting for the justice”, says Aitbek. ” It does n’t matter in terms of what … so she had a strong feeling for justice. Whenever she saw that someone is hurt and that he needs protection, she was always there” for people.

And yes, he says, the law does not go far enough- yet. However, it is just a start, demonstrating to the public that even the most powerful can be held accountable.

This trial will demonstrate to the public that “in Kazakhstan, a law is the same for everyone and everyone is treated equally in front of the trial,” he said.