“When I found my little brother’s cold body it was May, but my heart turned to winter.”

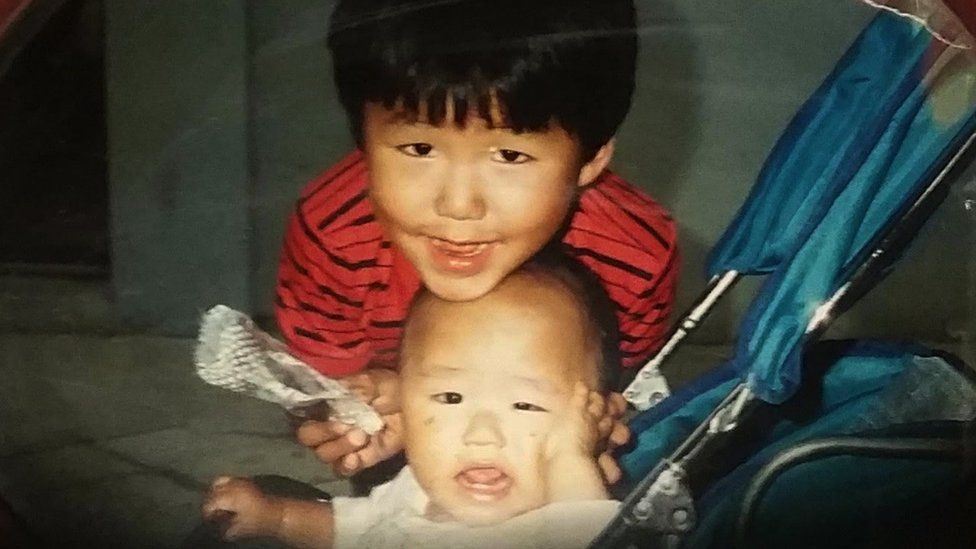

Jang Jun-ha’s brother, Jun-an, was only 35 when he took his life in 2018. Jang had called the police in South Korea’s capital Seoul after not being able to reach Jun-an on his mobile phone for days.

When they forced open his brother’s door, Jang found Jun-an lying lifeless on the bed. “I never thought my brother would take his own life,” he says.

This was despite Jun-an having tried to kill himself five years earlier, in 2013 – Jang thought he’d been happier since then after receiving treatment in a psychiatric clinic.

“It couldn’t have been perfect,” says Jang, “but we thought he was finding his way back into the world. He didn’t show any signs of suffering. I think he didn’t want to be a burden to the family.”

It is still really hard for Jang to talk openly about what his family has gone through because suicide is such a sensitive issue in South Korea. Earlier this year it announced new plans to try to bring down its suicide rates – some of the highest in the world.

South Korea is famous for K-pop and global companies like Samsung. But in this outwardly successful society, on average more than 35 people take their own lives every day and suicide is the leading cause of death among those aged 10 to 39.

Jang, 46, is doing his best to raise awareness by sharing his personal journey. At the time he found Jun-an’s body he’d actually been taking a course to become a suicide prevention instructor.

“I visited schools to educate children about the common signs of a person thinking about suicide and what can be done to help them. I tried to save other people’s lives.”

Family’s ‘only hope’

Jang had long thought of getting this training because his family had a high risk of suicide. He hoped they’d made it through their struggles and wanted to give something back to society.

Jang and Jun-an’s family went through a particularly difficult time in 2010, when South Korea severed all economic ties with the North. This was after the sinking of the warship Cheonan, which killed 46 sailors.

His father ran one of the few companies that did business with the North – and the sudden termination of relations led to the business going bankrupt.

The family had to separate and live in different places. The business his father ran failed and Jun-an became “our only hope”, says Jang, recalling the pressure put on his brother.

Jun-an had done well at school and planned to study abroad, but the family could no longer support him.

At the time of Jun-an’s suicide attempt in 2013, Jang was still busy paying off his family’s debts and was trying to become a qualified counsellor while doing his day job.

It was only after Jun-an’s death five years later that Jang asked to see his brother’s medical records – and found out he had been going to therapy every week for nearly a decade.

“Like many other Korean families, he was under great pressure to succeed. But finances were limited and life was hard for him,” says Jang.

“My brother was fiercely fighting depression. It breaks my heart that I didn’t notice this for so long.”

At 25.2 deaths per 100,000 people, South Korea’s suicide rate is the highest among the wealthy 38-member Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It is more than double the OECD average of 10.6 deaths.

South Korea launched its first national suicide initiative in 2004, a year after topping the OECD ranking – it has had the highest rate ever since, except in 2016 and 2017.

The country’s statistics agency says 12,906 people took their lives in 2022.

More than two in five of all deaths among teenagers (42.3%) are due to suicide. This rises to 50.6% for people in their 20s, and then dips to 47.9% for people in their 30s.

Jang’s brother was part of this generation struggling to get by.

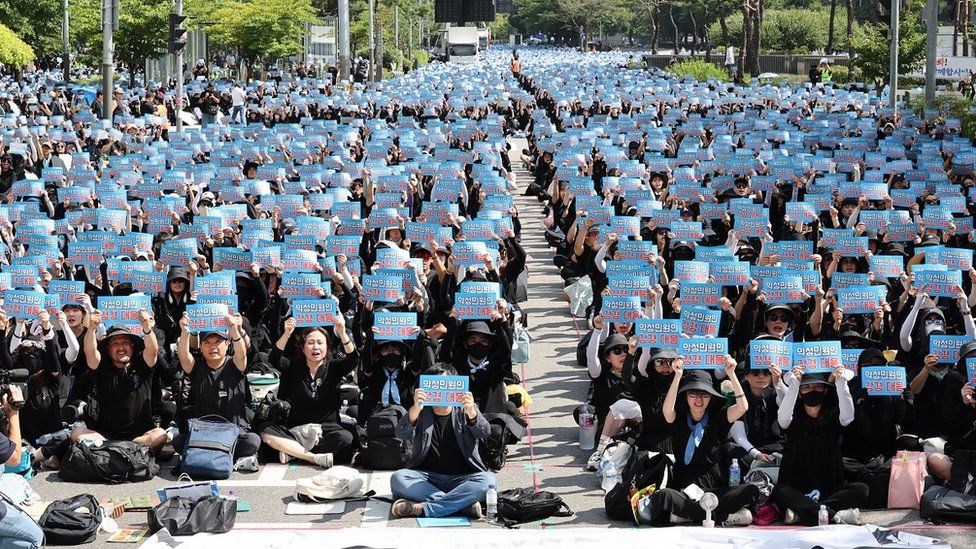

The South Korean government announced a five-year plan to prevent suicides in April, with the goal of reducing the country’s rate by 30%, which would move it off top spot in the OECD table.

Plans include a state-funded medical check-up for mental health every two years, greater support for local communities to look after vulnerable people, better moderation of explicit and harmful content online and a rapid system for reporting this content directly to the police.

Will the new plan work?

The health minister, who set the new target, has said it will not be an easy task.

While there is no magic formula to solve the suicide problem in South Korea, many point to the lack of budget. Its neighbour Japan also had one of the highest suicide rates in the world, peaking in 2003. But the rate has been gradually declining since then.

A recent joint study by Korean and Japanese researchers found that one of the main differences in suicide prevention policies between the two countries is money.

In 2018, South Korea’s budget for suicide prevention was about $16.8m (£13m) – just 2.1% of Japan’s budget of $793.7m.

High-pressure society

But it is not just about money. South Korea’s suicide rate is a mix of economic, social and cultural factors.

The country rose to become a global economic power after being torn apart by the Korean War, which ended in 1953. But this rapid economic growth did not lead to an expansion of state services, and instead contributed to rising inequality.

This birthed a society built on high levels of competition and success, which eventually led to many citizens suffering from psychological problems.

Experts have long highlighted the danger of a society that focuses too much on a person’s success, usually in terms of money or social status.

“Beyond the high suicide rate in South Korea, there is a sad story of a society with a weak welfare system, but one that is very success-oriented, usually reflected in how much wealth one acquires,” says Soong-nang Jang, dean at Chung-Ang University’s College of Nursing.

“And as traditional ties between family members and neighbours weaken, everyone seems to be fighting this battle for success on their own.”

‘Let’s talk’

The culture is slowly changing, but much remains to be done.

“South Koreans are so used to getting ahead in this hyper-competitive society, and Korea is not exactly a place where it’s easy to express your feelings,” says Yeon-soo Kim, director of LifeLine Seoseoul, a charity that provides a 24-hour helpline to suicide prevention services.

“People need more space to express their struggles and feelings freely and safely. We need to keep reminding people that there are different ways to succeed and really acknowledge that.”

Jang now works as a clinical psychologist at a mental health centre in Seoul, helping families who have been affected by suicide or people who have suicidal thoughts.

He also leads support groups for families like his who have lost loved ones to suicide.

“It’s a tough job. The family members are often the first to discover the body. They remember the scene very vividly and also describe what happened very graphically.”

Jang is aware of the emotional toll these conversations take on him.

“But this job is worth it when you see them getting better.”

And there has been a sense of acceptance and understanding in his own family too. As a qualified counsellor, he knew it was important to talk and he made the effort.

After his brother died, he visited his parents every weekend for a year. He shared what he had heard in the local support groups and comforted them.

Jang says his brother left a note behind saying sorry to his parents and him for leaving them.

But when the family visited his grave, Jang told his little brother: “It’s okay.”

“You don’t have to be sorry. We’re doing good, caring for each other,” says Jang. “So no need to be sorry, we’ll be back.”

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by issues in this article, the following resources may help:

- In the UK: BBC Action Line

- Elsewhere in the world: Befrienders Worldwide

Related Topics

-

-

10 February 2020

-