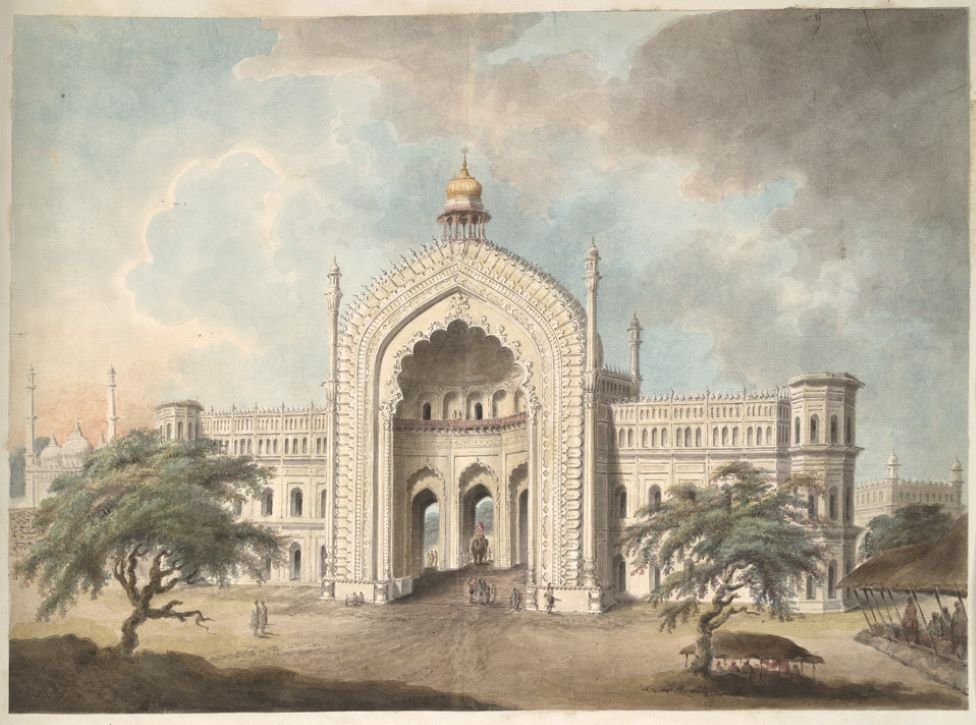

The painting above depicts the open area in front of Bara Imambara, a historical building complex in Lucknow, the capital city of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

Built in 1784 as part of a famine relief works project by Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula, the prince of the royal house of Oudh, it is one of the last great and palatial buildings constructed in the Mughal style. The complex includes several structures, including the Bhool Bhulaiya (a labyrinth) and the Asfi mosque.

Look at the painting again. You can see the outer gate of the complex, and the Imambara itself is out of view. To reach the imposing building, visitors have to pass through this gate and two large courtyards before reaching the central hall, which is one of the world’s largest arched constructions without the support of beams or pillars.

In the painting, straight ahead, there’s the Rumi Darwaza, the imposing gateway to old Lucknow. Then there’s a solitary elephant and some scattered people.

This evocative watercolour drawn by the once-obscure and long-anonymous Indian artist Sita Ram, will feature in an exhibition of Iconic Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art, organised by DAG, in Delhi later this month.

From June 1814 to early October 1815, Sita Ram travelled extensively with Francis Rawdon, also known as the Marquess of Hastings, who had been appointed as the governor general in India in 1813 and held the position for a decade. (He is not to be confused with Warren Hastings, who served as India’s first governor general much earlier).

As art historians tell the story, Lord Hastings sailed upstream with a vast retinue – his wife, and staff and a painter who he mentions only as a “Bengal draftsman” – in a flotilla of 220 boats over 15 months from the city of Kolkata (then Calcutta) to the distant reaches of Jind, now situated in Haryana.

The purpose of the long journey was to “meet the rulers in northern India, with a view to possible expansions of British control, and to monitor more closely an ongoing war in Nepal”, according to art historian Giles Tillotson.

During the journey, Sita Ram painted 229 large water colour paintings portraying the buildings and landscapes that unfolded along the way”. Together, they amount to a “continuous visual narration of the expedition and complement Hasting’s written account”, says Mr Tillotson.

JP Losty, a former curator of the British Library in London, wrote that “some of the paintings illustrating the river journey are among the most tranquil and beautiful creations in Indian painting”.

The paintings – averaging 40 by 60cm – were pasted into 10 annotated albums which Hastings took back home at the end of his term in India. They were passed down to his descendants and for a century and a half – 1820s to 1970s – Sita Ram’s works were “unseen by the outer world, and his name was unknown”.

In 1974, Hasting’s family sold two of the albums containing 46 paintings in an auction at Sotheby’s in London. As the album covers bore Sita Ram’s name, the world got a glimpse of this previously unrecognised artist and his work, according to Mr Tillotson.

“On this evidence alone, specialists of Indian paintings saw Sita Ram as one of the most important Indian artists of this period,” he says. “But still very little was known about him”.

As the paintings were offered for sale anonymously, there was no way of connecting Sita Ram with Hastings.

Twenty years later, the family decided to sell the remaining eight albums along with three others containing more paintings made by Sita Ram on later journeys in Bengal in 1817 and 1821. The collection was acquired by the British Library.

“It now appears that Hastings was not the artist’s only patron. After Hastings left India, he continued to work for other patrons, or he made other versions of his works, either to keep himself or sell to others,” says Mr Tillotson.

Sita Ram’s artworks contribute to the genre known as Company Paintings, distinguished by their use of watercolour, a departure from the conventional gouache, and executed on paper, assembled into folio-bound albums.

The paintings took their name after The English East India Company, founded in 1600, which was established for trading. But as the powerful multinational corporation expanded its control over India in the late 18th Century, it commissioned many remarkable artworks from Indian painters – Sewak Ram of Patna and Ghulam Ali Khan of Delhi were notable names – who had previously worked for the Mughals.

Not much is still known about Sita Ram. Hailing from Bengal, he seems to have been trained in the late Mughal school of Murshidabad, the capital of the prince of Bengal. “When the school fell by the wayside, artists like Sita Ram moved on to find patrons in the new cities emerging under British rule,” says Mr Tillotson.

Was Sita Ram a trained draughtsman? Losty seemed to think so. He wrote that Sita Ram’s work was “overlaid by exposure to a precise style of draughtsmanship” which he could have probably acquired through being trained as a botanical draughtsman or an architectural draughtsman “as well as his training in the English watercolour topographical style”.

Losty said many of Sita Ram’s paintings “promised to be of great interest in the discovery of India’s past before the advent of photography and the Archaeological Survey”.

Mr Tillotson says Sita Ram was “one of the most versatile and inventive of Indian artists working for European patrons in the early 19th Century”.

“Scenes such as this courtyard before the Imambara in Lucknow [in the painting] seem familiar to us 200 years later; all that has changed is an increasingly urban landscape that is now encroaching on the setting.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: