RESPONSIBILITIES TO Revolution

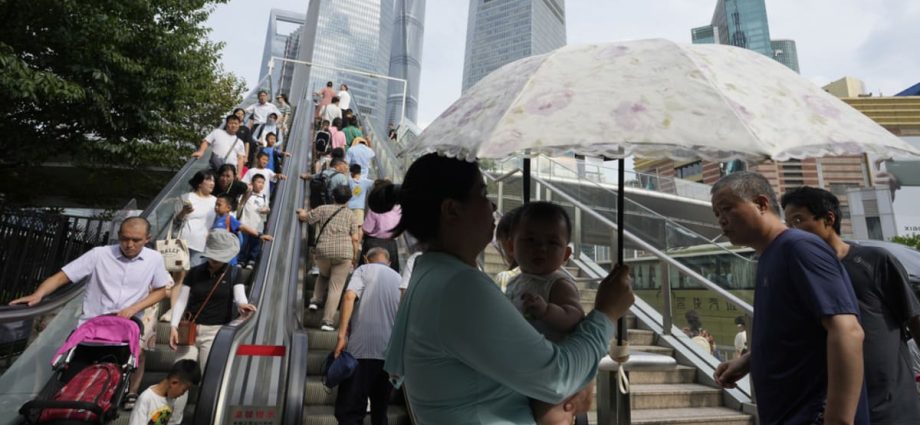

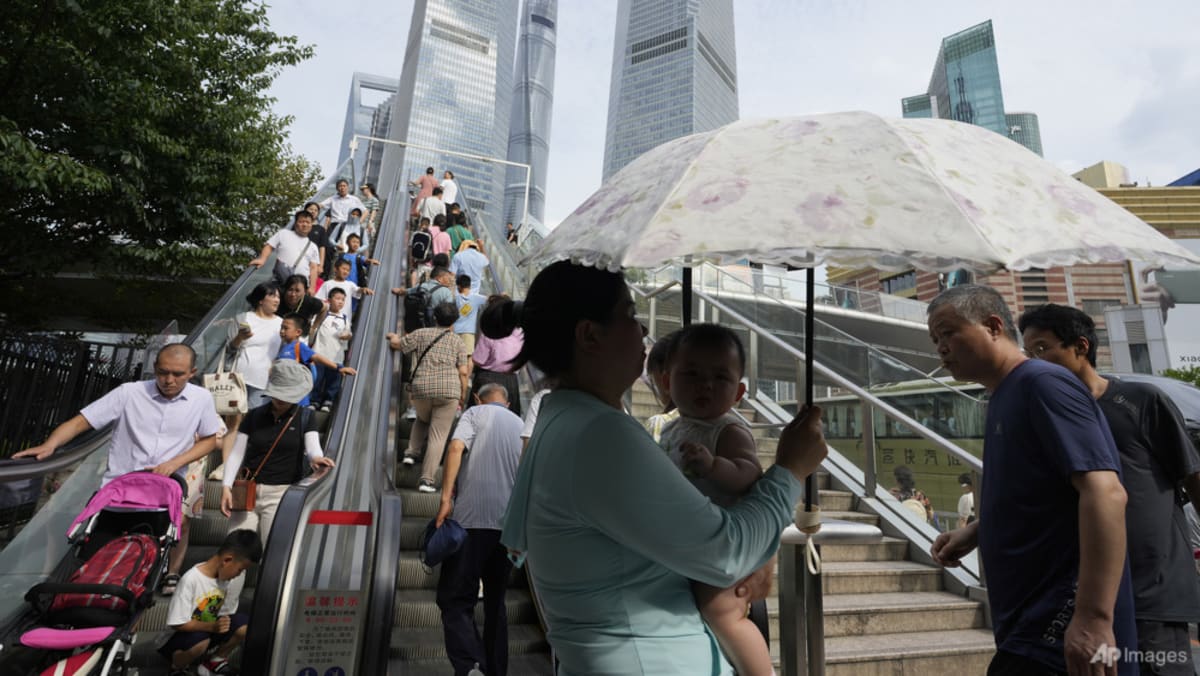

Regional challenges range from the banal to the more serious problems with China’s political economy. People of larger cities are hesitant to share their equivalent( if not absolute ) prosperity in China, as they are elsewhere. Timing is important as well, as evidenced by the slowing economy and the higher than 46 % youth unemployment rate.

The charge must also be taken into account. According to modeling done in 2014, granting urban hukou standing to China’s migrant workers may cost 1.5 percent of the country ‘ gross domestic product annually over a 15-year period. This amount would now be significantly higher. Although the national economic benefits would likely more than make up for these costs, the entire process might be unequal.

The more important problem is who pays. Local governments foot the bill for approximately 85 % of public service despite only receiving 50 % of the profits. The eagerness of most localities to increase social spending is seriously questioned by the extremely perilous nature of native government finances. The following are: & nbsp,” ,’

Hukou change would probably cause regional government revenue to experience even if overall GDP increases because only about 10 % of people in China( and very few metropolitan refugees) pay income tax. The implication is that more profound and even more contentious financial and tax reforms are necessary for sustainable hukou reform.

It’s possible that there are intellectual obstacles at work as well. For thousands of years, the Taiwanese government has employed a variation of the hukou program. Taiwan is one of many East Asian countries where similar techniques have been abolished, but usually by governments with distinctly more democratic and market-oriented policies.

This is not a stable position. The political and economic calculus of hukou reformation could theoretically change as demographic decline bites China, whose population is now declining. Whether China may adopt more extensive hukou transformation will function as a litmus test for whether Beijing’s commitment to global growth is genuine or merely facetious, at least in the short term.

Social risk scientist Henry Storey previously served as an editor for Young Australians in International Affairs and Foreign Brief. This article first appeared on The Interpreter, a site run by Lowy Institute.