The Pacific Islands have consistently sought a stronger regional voice since the establishment of the Pacific Islands Forum in 1971, most recently manifesting in the Blue Pacific Continent. But now increased attention from great powers threatens such regional efforts.

Over the past decade, concerns associated with the rise of China, particularly Beijing’s rapid naval modernization and growing strategic and commercial inroads in the region, have brought the Pacific Islands into the geopolitical limelight.

The United Kingdom’s “Pacific Uplift” (2019), Indonesia’s “Pacific Elevation” (2019), New Zealand’s “Pacific Reset,” (2018) and Australia’s “Pacific Step-up” (2018) also reflect this trend.

After the trilateral AUKUS deal garnered mixed reactions from the Pacific Islands, Australia’s Albanese administration has prioritized bilateral ties with the island nations, not only through high-profile diplomatic visits but also by stabilizing relations with China and placing climate change back on the agenda.

The Pacific Islands feature as major partners in Washington’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (2022) and the Roadmap for a 21st Century US-Pacific Islands Partnership (2022). The Partners in the Blue Pacific seeks to expand cooperation between the Pacific Islands and American partners on issues such as climate change and people-centered development.

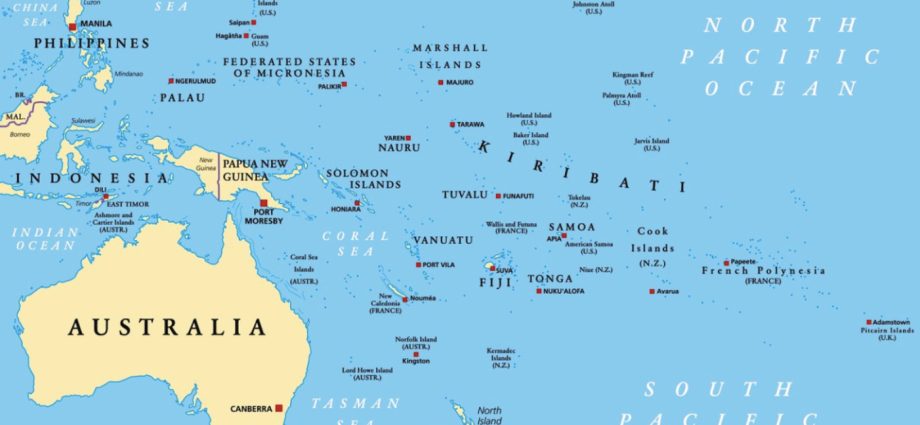

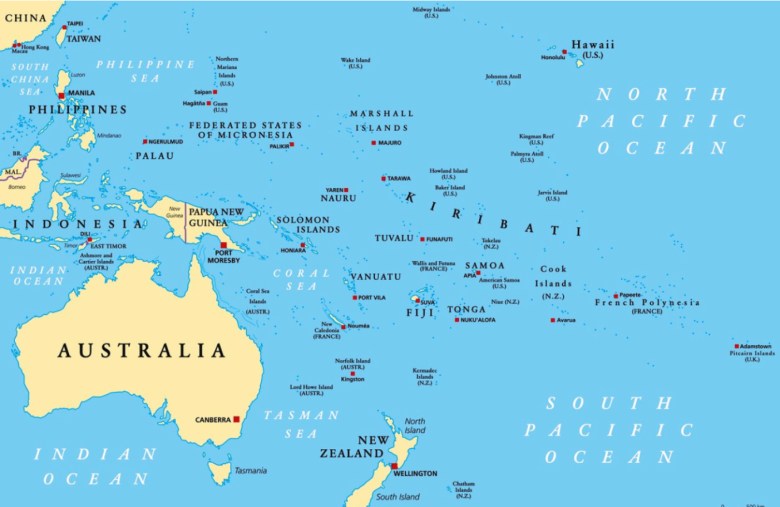

Under its Pacific Partnership Strategy, the United States has renewed the compacts of free association (COFA) with the Federal States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, while the agreement with the Republic of Palau has been extended.

The Marshall Islands is yet to settle the renegotiation of the COFA treaty, with the lingering effects of Washington’s atomic testing during the 1940s and 1950s acting as a holdup.

The compacts oblige Washington to protect those nations and allow it access to their territories. Citizens of compact nations can serve in the US military; significantly, the compact islands have a higher military participation rate than any US state.

Washington has also tried to strengthen its diplomatic presence. On his visit to Tonga in late July, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken criticized “problematic behavior” springing from China’s engagement in the region. It was his third visit to the Pacific Islands in two months.

The visit closely followed the State Department’s announcement that the United States plans to ramp up American diplomatic presence in the region to “catch up” with Beijing, which has permanent diplomatic facilities in eight of the 12 Pacific island states that Washington recognizes.

Furthermore, at the compact review signing ceremony with Palau, Blinken announced that Washington will commit a whopping US$7.1 billion to the Freely Associated States over the next two decades. (The Pacific Freely Associated States include the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of Palau.)

The United States is also set to host a second summit with Pacific leaders this September.

China has stayed close on the heels of such developments. Beijing has not only replaced Taiwan as a major investor and aid provider in the region, thus expanding acceptance of its One China Principle, but it has also criticized the “Band-Aid diplomacy” of the West, describing it as a mere temporary fix to the problems faced by the Pacific Islands that fails to bring any real socioeconomic progress.

China has thus emphasized the formation of the “China-Pacific Islands Community with a Shared Future” rooted in South-South Cooperation. Beijing has further enhanced its regional role from that of a predominantly commercial actor through the Belt and Road Initiative to a security provider under the Global Security Initiative. Qian Bo, China’s special envoy to the Pacific Islands, recently met Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown, who chairs the Pacific Islands Forum.

Such developments have drawn other powers to the region. In May 2023, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled a 12-point plan for the Pacific Islands focused on health care and community development at the Forum for India-Pacific Islands Cooperation summit in Port Moresby, highlighting the significance of the region for New Delhi’s Act East Policy.

The occasion also marked the first official visit by an Indian prime minister to Papua New Guinea (PNG). India might also expand its solar infrastructure STAR-C initiative under the International Solar Alliance to several nations in the region.

France also has huge stakes in the region – with 1.6 million citizens across seven overseas territories, the largest exclusive economic zone, and two sovereign forces with 2,700 military personnel – although its diplomatic influence remains modest.

While pushing for a “French alternative” to the unfolding Sino-US competition in the region, Emmanuel Macron has promised Vanuatu financial assistance for security, combating climate change, and education on an unprecedented presidential visit to the independent Pacific Island nations.

He has, further, promised to look into the dispute between Vanuatu and the French territory of New Caledonia and has also announced a new statute for New Caledonia, which will replace the 1998 Noumea Accord, while confirming the transfer of 200 more soldiers and 18 billion CFP francs (approximately $165 million) to the armed forces of New Caledonia.

Regionalism under threat?

Such developments are bound to impact the region enormously and the Pacific Islands are highly cautious about the loss of regionalism to great power competition.

The 2019 State of Regionalism Report published by the Pacific Islands Forum noted that the best way of preventing the region from getting embroiled in great power competition is for the Pacific Islands to act collectively as a “Blue Pacific Continent” prioritizing sovereignty and leveraging benefits from all actors involved.

ASEAN can serve as a lesson: While a strongly professed regional identity once helped it in safeguarding mutually held concerns and aspirations, growing external influence has fissured unity and weakened the region. It would seem that strengthening regionalism would allow the Pacific Islands to become friends with all and enemies to none.

The reality is more complex, however. In July 2023, the Solomon Islands and China agreed to enhance police cooperation as part of their security deal struck in 2022, elevating diplomatic ties to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

The 2022 agreement had heightened anxieties in the region. In March 2023, the United States, Australia and the UK unveiled details of the AUKUS plan as a response to China’s growing footprint in the Pacific, 18 months after the partnership was formally announced.

Not only did Solomons Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare criticize Australia and New Zealand for “suddenly withdrawing financial support worth millions of dollars” (a claim both countries deny), but he also stated that “nothing” could stop him from seeking China’s help in policing if disorder broke out in the Solomon Islands.

Sogavara is set to review a 2017 security treaty with Australia that provided police support to Honiara. Canberra views this as an opportunity to “revitalize the security relationship.”

The no-confidence motion recently raised against Vanuatu’s Prime Minister Ishmael Kalsakau over a bilateral security deal with Australia further reflects this trend as lawmakers worry about upsetting Beijing, Vanuatu’s major development partner.

Others have stepped closer to the United States. Fijian President Ratu Wiliame Katonivere seeks to balance Chinese influence by strengthening relations with Western democracies, a major policy departure from former prime minister and interim president Frank Bainimarama.

Fiji not only joined the Washington-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, which seeks to lessen economic dependency on China, but also scrapped the memorandum of understanding on police training and exchange signed with China in 2011. Furthermore, Prime Minister Rabuka ended the Chinese police presence in Fiji, citing differences in political and judicial systems. Officers from Australia and New Zealand will remain.

PNG presents a similar case. While Prime Minister Peter O’Neill shared close ties with Beijing, his successor, James Marape, has moved closer to the United States.

In May 2023, the two nations inked a deal on defense and maritime cooperation reportedly allowing American aircrafts and vessels to access PNG’s territory more extensively.

Note, however, that Beijing remains not only the top lender to Fiji, but also a major export partner of PNG. As geopolitical tensions simmer, leaders of Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia’s ruling FLNKS party, the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), PNG and Solomon Islands are deliberating on declaring a “neutral” position.

Turning challenges into opportunities

Such dependence casts a dense shadow of doubt on the ability of island nations to balance great power influence. Heavy economic reliance on any one external actor is also detrimental to fragile island economies that have been hit hard by Covid.

While Pacific Island states have denied taking sides, growing “Pacific militarization” not only threatens to fragment regionalism and hamper strategic neutrality, but might also overwhelm regional priorities such as climate change.

For instance, the International Atomic Energy Agency’s endorsement of Japan’s discharge of treated nuclear wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear plant is “deeply concerning” for the Pacific Islands. To China, it is a win as it has tarnished Japan’s image as a credible ally.

Furthermore, leaning towards either China or the United States (such as in the case of the Solomon Islands, PNG, and Fiji) can create a wedge between Pacific Island nations and hamper bilateral cooperation, thus impacting regionalism.

Despite this strategic tightrope, growing geopolitical interest in the region brings a myriad of opportunities to attain socioeconomic development and address environmental concerns.

Yet to translate such developments into developmental opportunities without compromising sovereignty and autonomy, the Pacific Islands should focus on collective capacity building, including greater regional cooperation at official forums, integrated efforts at civil society building, empowering youth and women and promoting stronger media literacy and independent media that strengthens their capacity to act in the regional interest.

Cherry Hitkari ([email protected]) is a non-resident Vasey fellow and young leader at Pacific Forum.

This article was originally published by Pacific Forum. Asia Times is republishing it with permission.